Baseball's Bridge Player: Dixie Walker From Ruth to Robinson

Think about standing on a baseball field in 1931 wearing a Yankees uniform, watching Babe Ruth take batting practice. Now picture yourself 16 years later on that same field, this time at Ebbets Field, standing next to Jackie Robinson as baseball tears down its color barrier. Only one player in baseball history lived both moments.

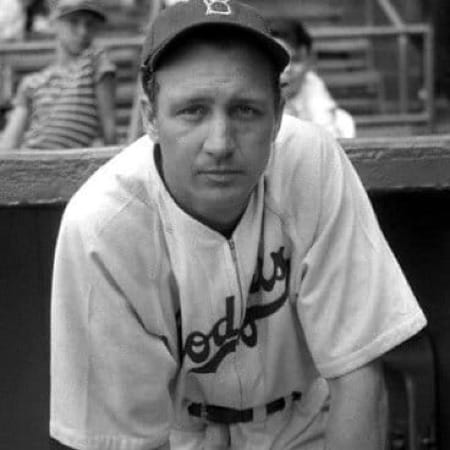

Fred "Dixie" Walker (OF, BRO) occupies a unique place in baseball history. That fact should make him a celebrated bridge figure between baseball's eras. Instead, it makes him one of the game's most complicated legacies.

1947: When Excellence Met Infamy

Walker turned 36 before the 1947 season. He was coming off a second-place MVP finish in 1946, when he hit .319 with 116 RBI. Brooklyn fans adored him as "The People's Cherce," their pronunciation of "Choice" reflecting the borough's love for their star right fielder. He was the most popular player in Dodgers history.

Then came spring training in Havana, and Branch Rickey's announcement that Jackie Robinson would join the Dodgers.

Walker organized a petition among his teammates opposing Robinson's promotion. He circulated it among the Dodgers' Southern players, including Bobby Bragan, Hugh Casey, and Carl Furillo. The petition stated the signatories would refuse to play with a Black teammate. Walker carried weight as the team's veteran leader and newly appointed National League player representative. His opposition mattered.

Manager Leo Durocher got word of the petition and called a midnight meeting in the barracks at Fort Gulick in the Panama Canal Zone. According to Durocher's autobiography, he told the players exactly what they could do with their petition. Branch Rickey backed Durocher completely. The petition collapsed, but the damage to Walker's reputation had begun.

Walker asked to be traded rather than play alongside Robinson. In a letter to Rickey, he didn't mention Robinson by name, but the intent was clear. Walker later explained he faced pressure from Birmingham business associates who threatened his wholesale business if he played with a Black man. "I didn't know if people would spit on me or not," he said years later.

The trade request was denied. Walker played the entire 1947 season.

Here's the part that complicates the narrative. Walker had one of his best seasons. He hit .306/.415/.427 with a 121 OPS+ and 4.0 WAR. He walked 97 times against just 26 strikeouts. His plate discipline had never been sharper. He and Robinson both contributed to Brooklyn's pennant run, appearing in the 1947 World Series against the Yankees.

By most accounts, Walker's relationship with Robinson improved during the season. He reportedly gave Robinson batting tips. After the pennant was clinched, Walker told reporters that Robinson was everything Branch Rickey said he was when he came up from Montreal. Some teammates remembered Walker being cordial. Others recalled ongoing tension.

Famed author Maury Allen investigated the alleged racism by Walker by learning the following. Walker later explained to author Maury Allen that he opposed Robinson's promotion because he feared it would damage his Birmingham businesses, a hardware store and a sporting goods store. Those fears proved unfounded. Within a month of the 1947 season, Walker recognized Robinson's exceptional talent. While they never developed the close friendship like the one Robinson had with Pee Wee Reese, Walker and Robinson maintained cordial relations throughout the season.

The Dodgers traded Walker to Pittsburgh after the season anyway. Rickey had not forgotten the petition.

That's the story everyone knows. Now here's the story that got lost.

From Villa Rica to the Bronx

Walker broke into the majors on April 28, 1931, with the New York Yankees. He was 20 years old. The Yankees had paid $25,000 for his contract after he hit .401 for Greenville in the South Atlantic League the previous summer. That was real money in 1931, the kind teams spent on can't-miss prospects.

The organization saw Walker as Ruth's eventual replacement in left field. He had power, he could run, and he had a strong throwing arm. In 1933, his first full season, Walker hit 15 home runs in just 328 at-bats while posting a .274 average and a 123 OPS+. The future looked bright.

Then came the injuries. Walker crashed into a fence during his 1931 rookie stint, damaging his shoulder. The injury recurred in 1935 after a slide into second base. Between 1934 and 1935, he appeared in just 25 games for the Yankees. His power disappeared. His throwing arm weakened. When Joe DiMaggio arrived in 1936, Walker was expendable.

The Yankees sold him to the Chicago White Sox in May 1936 for $20,000, a $5,000 loss on their investment. Walker was 25 years old, and his career as Ruth's heir was over before it really began.

The Journeyman Years

Walker bounced around the American League for the next three seasons. He hit .302 for the White Sox in 1937, leading the league with 16 triples, but injured his shoulder again and needed another surgery. Detroit acquired him in December 1937, and he hit .308 in 1938. But knee injuries limited him in 1939, and the Tigers gave up on him.

On July 24, 1939, the Brooklyn Dodgers claimed Walker off waivers. He was 28 years old. His career numbers looked mediocre: a .295 average in parts of eight AL seasons, chronic injuries, diminished power. Most players with that resume don't get second acts.

Walker got one.

"The People's Cherce" Is Born

Something clicked in Brooklyn. Maybe it was manager Leo Durocher believing in his stroke. Maybe it was getting healthy. Maybe it was just finding the right place at the right time. Whatever the reason, Walker became a star.

In his first game as a regular in 1940, he singled in the 11th inning to beat the Boston Braves. Brooklyn fans loved him immediately. They nicknamed him "The People's Cherce." From 1940 through 1947, Walker hit below .300 just once, a .290 mark in 1942 that still produced a 126 OPS+. He made five consecutive All-Star teams from 1943 to 1947. He finished in the top 10 of MVP voting five times.

The 1944 Peak: A Forgotten Masterpiece

Walker's 1944 season deserves more attention than it gets. At age 33, playing for a seventh-place team that finished 42 games behind the Cardinals, he won the National League batting title with a .357 average. He edged Stan Musial's .347. He posted a 172 OPS+. That's not a typo. Walker was 72 percent better than league average at the plate.

The advanced metrics tell the story his raw numbers miss. His 5.8 WAR led all National League position players. He hit .357/.434/.529 with 37 doubles, eight triples, and 13 home runs. His .434 OBP led the league. His wRC+ was 177, meaning he created runs at a rate 77 percent above average.

For context, that 172 OPS+ ranks among the greatest single seasons of the 1940s. Only a handful of players matched that production during the decade. Walker did it on a bad team, at age 33, in what should have been the beginning of his decline.

The 1945 Follow-Up: Baseball's Oddest RBI Crown

Walker followed his batting title with another remarkable season in 1945. He hit .300 with a 128 OPS+ and led the National League with 124 RBI. Here's what makes that fascinating: he hit just eight home runs.

Eight home runs. 124 RBI.

That's 15.5 RBI per home run, one of the highest ratios in baseball history for an RBI champion. Walker did it with 42 doubles, nine triples, and by hitting .300 with runners on base. He drove in runs the old-fashioned way, by putting the ball in play and moving runners along.

His 5.2 WAR in 1945 again ranked among the league leaders. In back-to-back seasons at ages 33 and 34, Walker posted a combined 11.0 WAR. That's an average of 5.5 WAR per season when most players are declining.

The Statistical Case Hidden by Circumstance

Walker's career WAR of 45.0 doesn't jump off the page. But look closer at his peak years from 1942 to 1947. In those six seasons, he posted 25.8 WAR despite playing in a low-offense era during World War II. His cumulative OPS+ over those seasons was 130. He was 30 percent better than league average for six straight years.

His career .306/.383/.437 slash line translates to a 121 OPS+. That places him among the better hitters of his generation. His .383 OBP ranks in the top tier of 1940s players. His 378 rOBA (runs created above average per out) shows he was a consistently above-average offensive force.

The problem? Injuries robbed him of his age 25 to 27 seasons, when players typically accumulate their best counting stats. He didn't become a regular until age 29. By the time he established himself as a star, he had already lost his prime years to shoulder and knee problems.

If Walker stays healthy with the Yankees from 1934 to 1938 and produces at even replacement level, he adds another 5 to 10 WAR to his career total. If he becomes a regular at age 25 instead of 29, his counting stats look completely different. He finishes with 2,500+ hits instead of 2,064. He accumulates 1,300+ RBI instead of 1,023.

Baseball history is full of "what ifs." Walker's career is a reminder that timing matters as much as talent.

The Ruth-to-Robinson Bridge

Walker was the only player to be teammates with both Babe Ruth and Jackie Robinson. That 16-year span from 1931 to 1947 encompassed baseball's most transformative era. When Walker played his first game, baseball still looked much like it had in 1910. By his last game, the sport was integrating, television was arriving, and the modern game was taking shape.

Walker witnessed all of it. He played with the greatest slugger of the Dead Ball era's aftermath. He played alongside the man who broke baseball's color barrier. He saw the game change from one generation to the next.

His statistics place him among the best players of the 1940s. His 1942 to 1947 peak compares favorably to many Hall of Famers. But the Hall of Fame isn't just about numbers. It's about legacy, and Walker's legacy is complicated by his resistance to integration.

The Unresolved Question

Should a 172 OPS+ season matter as much as a petition? Should 45.0 WAR and a .306/.383/.437 career line be weighed against a moral failing that the player himself later regretted? These aren't easy questions, and baseball hasn't answered them.

Walker died of colon cancer on May 17, 1982, in Birmingham, Alabama. He was 71 years old. He spent 52 years in baseball as a player, coach, manager, and scout. He won a batting title, an RBI crown, and played in two World Series. He also organized a petition to keep Jackie Robinson off his team.

Both things are true. Both things matter. And both things will define how we remember baseball's bridge player, the only man to stand on a field with both Babe Ruth and Jackie Robinson, who witnessed baseball's transformation and played a complicated role in its greatest chapter.