The Catcher Who Carried a Gun: Moe Berg's Secret War

Most catchers worry about stolen bases and passed balls. Moe Berg worried about atomic bombs.

On December 18, 1944, Berg sat in the front row of a physics lecture at the University of Zurich. He wasn't there to learn. He was there to kill. Hidden in his coat pocket was a pistol. In another pocket, a cyanide tablet. His orders were clear: if German physicist Werner Heisenberg revealed that Nazi Germany was close to building an atomic bomb, Berg was to shoot him dead. Right there in the lecture hall.

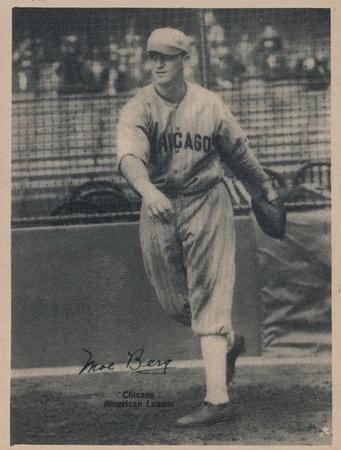

This was a long way from catching for the Chicago White Sox.

The Weakest Bat, The Sharpest Mind

Morris "Moe" Berg never belonged in the major leagues. At least not based on his baseball skills. Over 15 seasons from 1923 to 1939, he compiled a .243 batting average with just six career home runs. His -4.7 WAR tells you everything you need to know. He was worse than a replacement-level player. His best season came in 1929 with the White Sox when he hit .287 with an OPS+ of 64. Still well below average.

But Berg had something no other catcher possessed: he could discuss Plato in ancient Greek, recite poetry in Sanskrit, and argue philosophy in any of 15 languages.

At Barringer High School in Newark, he mastered Latin, Greek, and French. At Princeton, where he graduated magna cum laude, he added including Spanish, Italian, German, and Sanskrit. While playing baseball for Princeton, he'd call plays in Latin. Imagine trying to steal signs when the catcher is speaking a dead language.

He picked up Japanese, Chinese, Korean, Arabic, Portuguese, and Hungarian during studies at the Sorbonne in Paris and Columbia Law School. Teammates called him "Professor." Opposing players thought he was showing off. He was just bored.

Berg bounced around the majors. Brooklyn in 1923. Five years with the White Sox. Stops in Cleveland and Washington. He finished his career with five seasons in Boston, mostly riding the bench. In 1938, he played just 10 games. In 1939, his final season, he appeared in only 14.

He knew he wasn't good enough. But he loved the game. And baseball gave him something more valuable than statistics. It gave him cover.

A Kimono and a Camera in Tokyo

When Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig toured Japan in 1934 for a series of exhibition games, fans were puzzled. Why would the greatest sluggers in baseball bring along a .240-hitting backup catcher? Berg barely played in the games. He seemed more interested in sightseeing than baseball.

One afternoon, Berg dressed in a traditional kimono and carried a bouquet of flowers. He told teammates he was visiting the daughter of an American diplomat at St. Luke's Hospital. The hospital was the tallest building in Tokyo. Berg took the elevator to the top floor. He never delivered the flowers.

Instead, he climbed to the roof and pulled out a 16mm movie camera. For the next several minutes, he filmed everything he could see. Tokyo Harbor. Railway yards. Military installations. Industrial facilities. The footage was grainy but detailed. He smuggled the film back to the United States.

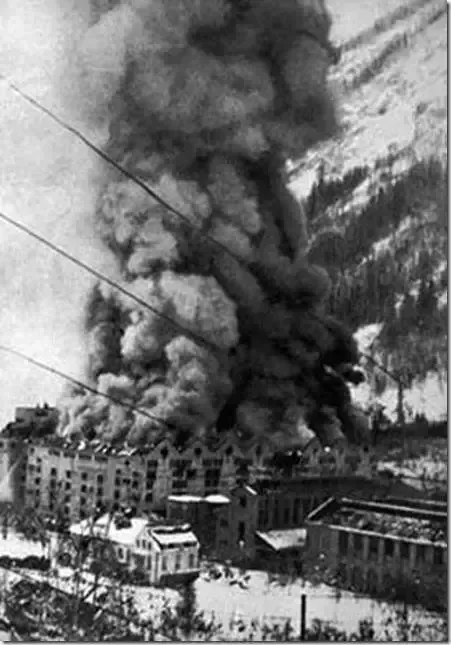

Eight years later, in April 1942, General Jimmy Doolittle studied Berg's films while planning the first American bombing raid on Tokyo. The mission was a success. Sixteen B-25 bombers struck the Japanese capital. Berg's footage had helped them find their targets.

The catcher who couldn't hit a curveball had just helped America strike back after Pearl Harbor.

From the Dugout to the OSS

Berg's playing career ended in 1939. He stayed on as a coach for the Red Sox through 1941, but his mind was already elsewhere. In 1942, he conducted a goodwill tour of South America. The tour had another purpose. Berg was gathering intelligence.

In August 1943, the Office of Strategic Services came calling. The OSS was America's wartime spy agency, the predecessor to the CIA. They needed someone who could speak multiple languages, understand complex scientific concepts, and blend in anywhere. Berg was perfect.

His first major assignment sent him to newly liberated Rome in 1944. American forces had just pushed the Germans out of Italy. Berg's job was to track down Italian scientists and find out what they knew about Germany's atomic bomb program. He conducted interviews, gathered documents, and sent reports back to Washington. The Nazis had been working with Italian physicists. Berg needed to know how much progress they'd made.

The news was troubling but not conclusive. Germany was working on a bomb. But how close were they?

Death in a Lecture Hall

That question led Berg to Zurich in December 1944. Werner Heisenberg was one of the greatest physicists in the world. He'd won the Nobel Prize. He understood quantum mechanics better than almost anyone alive. And he was working for Nazi Germany.

American intelligence needed to know if Heisenberg was building Hitler a bomb. They gave Berg an impossible task. Attend Heisenberg's lecture. Determine if Germany was close to a nuclear weapon. And if the answer was yes, kill him.

Berg posed as a Swiss graduate student in physics. American scientists had tutored him for weeks. He'd studied quantum theory, atomic physics, and Heisenberg's own work on S-matrix theory. He knew enough to understand what he was hearing. Maybe.

He arrived early and took a seat in the front row. Close enough to shoot. The pistol felt heavy in his pocket. Heisenberg entered and began his lecture. Berg listened carefully to every equation, every comment, every hesitation. He watched Heisenberg's body language. His confidence. His certainty.

The lecture was theoretical. Abstract. Nothing about uranium enrichment or bomb design. Nothing about weapons at all. Berg made his assessment. Germany was not close. The Nazi atomic program was years behind the Manhattan Project.

But Berg wasn't finished. He needed to be certain. That evening, he arranged an invitation to a dinner party where Heisenberg would be present. They talked for hours. Berg asked careful questions. Heisenberg answered them. By the end of the night, Berg was sure. Germany didn't have a bomb. They weren't going to get one before the war ended.

He kept the gun in his pocket. Heisenberg lived. Berg's report went to the highest levels. President Franklin Roosevelt read it. So did Winston Churchill. They trusted his judgment. A backup catcher who'd spent 15 years on major league benches had just made one of the most important intelligence assessments of the war.

Trailer for the documentary about Moe Berg

Moe Berg Documentary Trailer

The Medal He Refused

Berg continued working for the OSS through 1945 and into 1946. He operated in Switzerland, gathering intelligence and tracking scientists. When the war ended, America wanted to thank him. On October 10, 1945, he was awarded the Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor in wartime.

On December 2, 1945, Berg refused it. He couldn't explain why he deserved it. His work was classified. He couldn't tell anyone what he'd done. The secrecy that had protected him during the war now prevented him from accepting recognition. So he said no.

After leaving the OSS, Berg never held another steady job. For the next 26 years, he lived as an itinerant intellectual. He read voraciously. He attended lectures. He visited friends and wore out his welcome. In 1951, he tried to convince the newly formed CIA to send him to Israel. They declined.

He refused to write his memoirs. He had stories that would have made him famous and wealthy. But he wouldn't tell them. The secrets stayed locked inside.

Berg died on May 29, 1972. His last words, according to witnesses, were about the baseball scores. After everything he'd done, he still cared about the game. His sister Ethel later accepted the Medal of Freedom on his behalf. She donated it to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, where it hangs today.

Two Lives, One Man

Moe Berg's career WAR was -4.7. He was one of the worst hitters in baseball history to play 15 seasons. But his OPS+ of 49 doesn't measure what mattered. His 15 languages. His ability to film Tokyo Harbor without getting caught. His courage to sit in that lecture hall with a gun and a cyanide pill, ready to kill or die.

Baseball gave Berg access to places other spies couldn't reach. His glove got him into Japan. His reputation as an educated curiosity made him seem harmless. Who would suspect a backup catcher of espionage?

The game he loved became his cover. And when his country needed someone who could think in multiple languages and make life-or-death decisions in a foreign lecture hall, they called the guy who hit .243.

Most catchers are remembered for home runs or Gold Gloves. Moe Berg is remembered for the shot he didn't take.