The Deal That Changed Baseball Forever

The Deal That Changed Baseball Forever: How Harry Frazee Sold a Dynasty

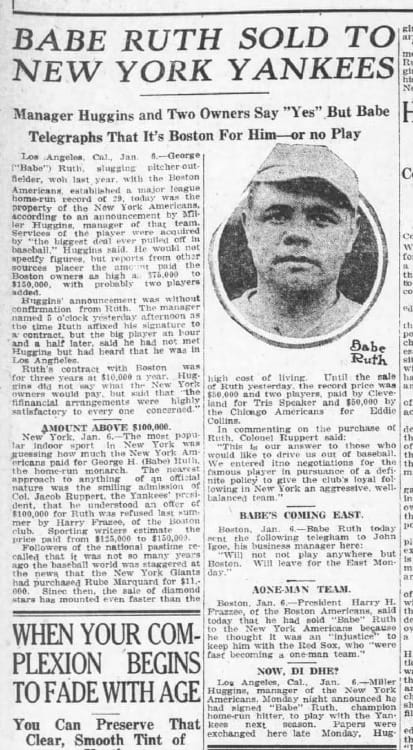

The winter of 1919 should have been a victory lap for Harry Frazee. His Boston Red Sox had won the World Series just a year earlier. They had Babe Ruth (OF/RHP, BOS), a 24-year-old phenomenon who'd just shattered the single-season home run record with 29 bombs while posting a ridiculous 1.114 OPS.

Instead, Frazee was drowning.

A Theater Man's Baseball Nightmare

Harry Frazee never really wanted to be a baseball owner. He was a Broadway producer first, a businessman second, and a Red Sox owner a distant third. That priority list would cost Boston an 86-year championship drought.

By November 1919, Frazee's world was collapsing. His theatrical productions were flopping. The war years had crushed attendance at Fenway Park. Gate receipts dropped 35% in 1918, even after winning the World Series. Now he faced a brutal reality: the promissory note he'd used to buy the Red Sox from Joseph Lannin was due. Immediately.

Frazee didn't have the cash. He owned valuable assets, a World Series-winning baseball team, the contract of the game's biggest star—but he was effectively broke. He needed money fast, and he needed a lot of it.

The timing couldn't have been worse. Frazee also wanted to buy the Harris Theater on Broadway and purchase the remaining shares of the Fenway Realty Trust that controlled his ballpark. He was a man with champagne dreams and a beer budget, except his brewery was going bankrupt.

The Yankees Pounce

Jacob Ruppert saw blood in the water.

The Yankees co-owner was everything Frazee wasn’t, fabulously wealthy from his family's brewing empire, laser-focused on building a winning baseball team, and patient enough to wait for the right moment. That moment arrived in December 1919.

Ruppert had watched Ruth demolish American League pitching all season. The numbers were absurd. Ruth's 29 home runs weren't just a record; they were more than five entire AL teams hit that year. The Yankees as a team managed only 45 homers in 1919. Ruth alone would have accounted for 64% of their output.

His 217 OPS+ meant Ruth was 117% better than the average American League hitter. Nobody else was close. Ty Cobb (OF, DET) finished second in OPS at .942. A great season by any measure, but Ruth's 1.114 OPS made Cobb look ordinary. Joe Jackson (OF, CHW) checked in at .928. George Sisler (1B, STL) posted .921. Then there was a massive drop to everyone else.

When Ruppert allegedly asked manager Miller Huggins what the Yankees needed to win, Huggins supposedly replied, "Get Ruth from Boston." Ruppert had been eyeing Ruth since watching him crush a home run at the Polo Grounds in 1918. Now he had his opening.

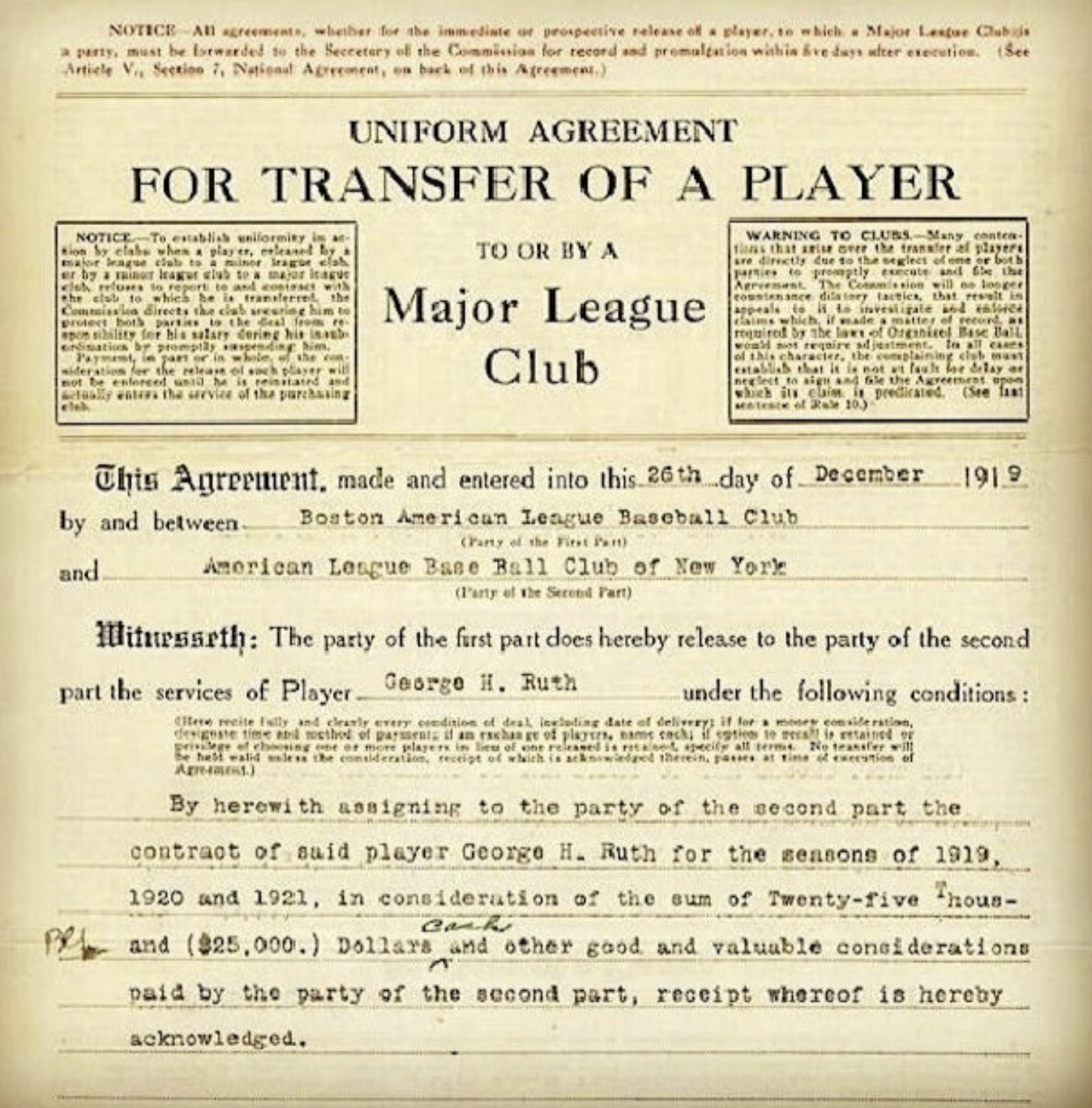

A Deal More Complex Than Anyone Knew

The announced terms seemed simple enough: $100,000 cash for Ruth's contract, payable in four annual installments of $25,000 at 6% interest. The first payment was made December 19, 1919. The deal was consummated December 26, 1919, but kept quiet until January 5, 1920.

That $100,000 was double what any player had ever been sold for. It made headlines across the country. What didn't make headlines was the rest of the deal.

Ruppert also made a personal loan to Frazee for $300,000, with Fenway Park as collateral. This loan was finalized on May 25, 1920, after Frazee used it to pay off Lannin and buy out the Taylor family's shares in the Fenway Realty Trust. Ruppert now held the mortgage on Fenway Park.

There was more. The Yankees agreed to pay the Red Sox $10,000 to help cover Ruth's new salary demands. Ruth had been making $10,000 per year under his 1919 contract, but he wanted $20,000. The Yankees negotiated him down to $10,000 with $21,000 in bonuses spread over 1920-1921. By having Boston chip in, Ruppert effectively reduced his purchase price.

Here's the kicker: According to research by Michael Haupert, professor of economics at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse, when you factor in the loan interest Frazee paid Ruppert over the years, Frazee actually ended up paying Ruppert more money than he received for Ruth. By the time the deal finally closed, Ruppert had received nearly three times as much from the Red Sox owners as he paid for Ruth.[3] The Yankees didn't just get Babe Ruth—they got him for nothing, and then profited from the loan besides.

It was the steal of the century disguised as the sale of the century.

Ruth's Feelings: Boston or New York?

Ruth's initial reaction? "Will not play anywhere but Boston."

When his business manager Johnny Igoe telegraphed news of the sale, Ruth fired back that telegram from California. He'd invested in the cigar business in Boston. He had associations there. He preferred playing for the Red Sox.

That lasted about five minutes.

Miller Huggins tracked Ruth down on a golf course in Los Angeles. After some negotiation, Ruth agreed to the Yankees' terms. The money was good. The Polo Grounds' short right field porch was better. New York was the biggest stage in America, and Ruth had a showman's instincts.

Would Ruth have remained primarily a pitcher in Boston? Almost certainly not. In 1919, he appeared in just 17 games as a pitcher, going 9-5 with a 2.97 ERA (102 ERA+). Manager Ed Barrow had already made the shift; Ruth played 111 games in the outfield. The experiment was working. Ruth posted 9.1 WAR as a hitter and 0.8 WAR as a pitcher, nearly 10 WAR combined.

But Boston's decision-makers knew Ruth was trouble. He jumped the team multiple times in 1919. He drank heavily. He stayed out late. He was "selfish and inconsiderate," according to Frazee's later spin. The front office wanted him gone almost as badly as they needed the money.

New York Celebrates, Boston Rationalizes

The New York Times greeted the announcement with barely contained glee. They boldly predicted a pennant and noted "great excitement" among city fans. One columnist wrote that "Manhattan's fondest dreams of having a World Series at the Polo Grounds between the Giants and Yankees now becomes a tangible thing."

Yankees pitcher Bob Shawkey captured the clubhouse mood: "Gee, I'm glad that guy's not going to hit against me anymore. You take your life in your hands every time you step up against him."

Boston's reaction was... complicated.

The Boston Globe's headline read "Red Sox Sell Ruth for $100,000 Cash." Some Boston papers actually backed Frazee's spin, suggesting the sale made sense. One editorial argued that fans would eventually agree with Frazee once they "sized up the affair," comparing it to when the Sox let Cy Young and Tris Speaker go and still won championships.

Frazee tried his best to sell it. "I should have preferred to have taken players in exchange for Ruth, but no club could have given me the equivalent in men without wrecking itself," he told reporters. "With this money the Boston club can now go into the market and buy other players and have a stronger and better team."

He even took shots at Ruth's character: "While Ruth, without question, is the greatest hitter that the game has ever seen, he is likewise one of the most selfish and inconsiderate men that ever wore a baseball uniform."

Not everyone bought it. Johnny Keenan, president of the Royal Rooters Red Sox fan club, was devastated: "Ruth was 90% of our ball club last Summer. The Red Sox management will have an awful time filling the gap caused by his going. Surely the gate receipts will suffer."

Keenan nailed it. Ruth wasn't just good—he was the whole show.

The Birth of a Dynasty

Was the Ruth sale THE turning point that created the Yankees dynasty?

Yes. Unequivocally, yes.

Before Ruth, the Yankees had never won an American League pennant. Not once in their 17-year existence. They finished third in 1919 with an 80-59 record—respectable but not championship caliber.

Ruth arrived in 1920 and obliterated his own record by smashing 54 home runs. He posted an otherworldly 1.379 OPS and 11.9 WAR. The Yankees won 95 games, their franchise record at the time, and drew nearly 1.3 million fans to the Polo Grounds, more than double their previous attendance record.

They won their first pennant in 1921. First World Series title in 1923. Built Yankee Stadium, "The House That Ruth Built," which opened in 1923. It won 11 pennants and eight World Series championships during Ruppert's lifetime.

Meanwhile, Boston cratered. They finished sixth in 1919 at 66-71. After selling Ruth, they plummeted to last place and didn't post a winning record again until 1934. They didn't win another pennant until 1946. Didn't win another World Series until 2004.

Eighty-six years. The Curse of the Bambino wasn't just superstition; it was what happens when you trade a once-in-a-generation talent because you'd rather finance Broadway shows than build a baseball team.

The Bigger Picture: A Rigged Game

Here's something that doesn't get mentioned enough: Frazee's options were severely limited by American League politics.

AL President Ban Johnson hated Frazee. He'd been trying to force Frazee out for years. Johnson pressured the "Loyal Five" teams—Cleveland, Detroit, Philadelphia, St. Louis, and Washington—to refuse any trades with Boston. Frazee could only deal with the Yankees or the Chicago White Sox.

Chicago offered Shoeless Joe Jackson and $60,000. Ruppert offered $100,000 cash plus the $300,000 loan. Frazee needed both the cash and the loan to survive. Johnson had effectively engineered a situation where Frazee had to sell to New York on New York's terms.

This wasn't just a bad baseball decision. It was a structural failure of league governance that concentrated talent in the largest market. Some contemporary editorials even warned about "the concentration of baseball playing talent in the largest cities" being "a bad thing for the game."

They were right. The Yankees have won 27 World Series titles. The Red Sox went 86 years between championships. That gap started on December 26, 1919.

What Frazee's Money Bought

Frazee used his cash to save his theater business. He eventually produced "No, No, Nanette," a massive Broadway hit that ran in New York, London, Chicago, and Australia. He made millions.

He also used the money to pay off Lannin, buy out the Taylor family, and purchase the Harris Theater. From a personal financial standpoint, Frazee came out fine.

The Red Sox? He left them in bankruptcy while he focused on his shows. The team didn't recover for a generation.

Ruppert, meanwhile, reinvested every Yankees profit back into the team. He never paid himself dividends. He just kept building, kept acquiring talent (much of it from Boston), and kept winning.

That's the difference between an owner who saw baseball as a business opportunity and an owner who saw it as a legacy.

The Verdict

The sale of Babe Ruth wasn't just a bad deal. It was baseball malpractice enabled by league politics, executed by a desperate theater producer who valued Broadway over Boston, and finalized with contract terms that actually made money for the buyer.

Ruth went from hitting 29 home runs in 1919 to 54 in 1920 to 59 in 1921 to 60 in 1927. He finished his career with 714 homers, a .690 slugging percentage, and 162.2 WAR. He changed how baseball was played, making the home run the game's central attraction.

The Yankees became American sports' greatest dynasty.

The Red Sox became a cautionary tale about what happens when you sell your soul for a Broadway show.

Harry Frazee got his theater.

New York got Babe Ruth.

Boston got 86 years of heartbreak.

And baseball was never the same.