The Strike Zone: A History of Baseball’s Most Contested Territory (part 1)

For more than a century, the strike zone has been baseball's most debated piece of real estate. It's invisible, but it's always there. The rulebook defines it, but umpires interpret it. Since 1900, it's been redrawn at least six times. Each change was a response to the never-ending battle between pitchers and hitters.

The story of the strike zone is really the story of baseball itself. It's a game that's always trying to find balance between offense and defense. Between tradition and change. Between what the rules say and what actually happens on the field.

1950: Shrinking the Zone

By mid-century, baseball had changed. The dead-ball era was over. Babe Ruth's power revolution in the 1920s had transformed the game. Sluggers like Ted Williams, Joe DiMaggio, and Stan Musial kept it going. Offense was king. The game's leadership saw no reason to help pitchers.

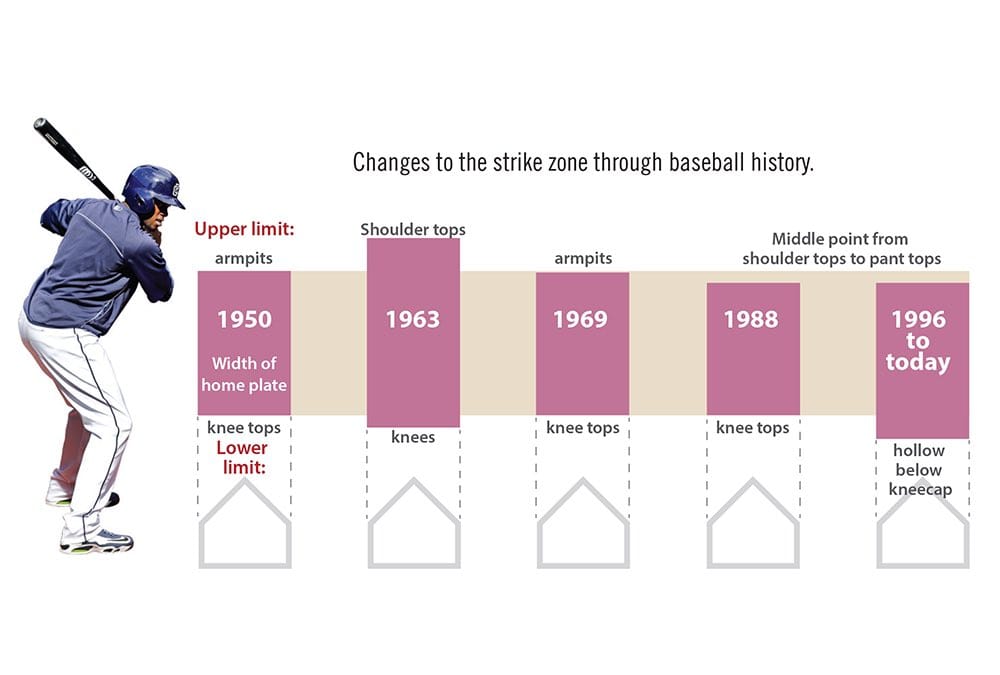

In 1950, Major League Baseball redefined the strike zone. They shrunk it from shoulders-to-knees down to armpits-to-knees. The change was subtle but important. By lowering the top of the zone, MLB gave hitters a better chance to lay off high pitches. Pitches that would have been strikes in the dead-ball era.

The 1950 adjustment made sense for the times. Offense was good for the game. Home runs sold tickets. Television was just starting to broadcast games nationally. Baseball's leaders understood something simple: a 2-1 pitcher's duel might be beautiful, but a 7-5 slugfest put fans in the seats.

1963: Expanding It Back

By the early 1960s, things had swung too far the other way. Offense wasn't just strong anymore. It was overwhelming. Roger Maris had just broken Babe Ruth's single-season home run record in 1961. League officials decided scoring had become too easy.

So in 1963, Major League Baseball expanded the strike zone again. They moved the upper boundary from the armpits back up to the top of the shoulders. The zone was shoulders-to-knees again, just like before 1950.

The official 1963 definition read: "The Strike Zone is that space over home plate which is between the top of the batter's shoulders and his knees when he assumes his natural stance."

At first, it worked. Pitchers got some leverage back. Offense cooled down a bit. But the change also set the stage for one of the most extreme imbalances in modern baseball history.

1969: The Year of the Pitcher and the Response

The 1968 season was statistically bizarre. It was the Year of the Pitcher. The numbers were staggering.

Bob Gibson posted a 1.12 ERA. That's the lowest single-season mark in the modern era for a qualified starter. Denny McLain won 31 games. He was the last pitcher to win 30 in a season. Don Drysdale threw 58 consecutive scoreless innings. Luis Tiant led the American League with a 1.60 ERA.

Carl Yastrzemski won the AL batting title with a .301 average. He was the only player in the league to finish above .300.

Across both leagues, pitchers threw 339 shutouts. The combined league batting average was .237. Strikeouts outnumbered walks by nearly two to one. Runs per game fell to 3.42. That was the lowest since the dead-ball era.

Baseball had a problem. The game had become unwatchable for casual fans. Offense—the lifeblood of entertainment—had been choked out. Dominant pitching was part of it. The expanded strike zone was another part. And those elevated pitcher's mounds gave hurlers even more of an advantage.

Major League Baseball acted fast. For the 1969 season, they made two big changes.

First, they lowered the pitcher's mound from 15 inches to 10 inches. That reduced the downward angle pitchers had been using.

Second, they shrunk the strike zone again. It went from shoulders-to-knees back down to armpits-to-knees. The same dimensions as 1950.

The 1969 definition: "The Strike Zone is that space over home plate which is between the batter's armpits and the top of his knees when he assumes a natural stance."

The impact was immediate. In 1969, the combined league batting average jumped to .248. Runs per game increased to 4.07. Balance had been restored. Baseball had pulled itself back from the edge.

1988: Tightening the Top Again

Even after the 1969 fix, the strike zone remained a problem. The rulebook said armpits to knees. But umpires often called it differently. The upper edge was all over the place. Some umpires called letter-high fastballs as strikes. Others didn't.

In 1988, Major League Baseball redefined the strike zone again. This time they got very specific. The new definition said the upper limit was "a horizontal line at the midpoint between the top of the shoulders and the top of the uniform pants." The lower edge stayed at the top of the knees.

This was a big change. The midpoint between shoulders and belt is lower than the armpits. So the 1988 definition shrunk the zone again. Taller pitchers who had been exploiting the high strike lost some advantage.

The reason was clear. MLB wanted to close the gap between what the rulebook said and what actually happened. Umpires had been inconsistent on high strikes for years. By lowering the official upper boundary, MLB hoped to standardize things. They wanted to give hitters more clarity about what would be called.

1996: Lowering the Bottom

The 1988 change fixed the top of the zone. But by the mid-1990s, another problem showed up. The bottom edge was being called inconsistently too. Pitchers felt they were losing strikes on pitches that just grazed the knees.

In 1996, Major League Baseball adjusted the lower boundary. They moved it from the top of the knees down to the hollow beneath the kneecap. This gave pitchers back some territory at the bottom. A small but meaningful expansion that rewarded breaking balls and sinkers that dipped low.

The 1996 definition is basically the strike zone we still have in the rulebook today. From the midpoint between the shoulders and the top of the pants down to the hollow beneath the kneecap. Over the width of home plate.

The Gap Between Rule and Reality

But here's the thing. The rulebook definition and the actual zone have never matched up perfectly.

Even with the 1988 and 1996 adjustments, umpires kept calling the zone their own way. Some umpires had reputations for wide zones. Others for tight ones. Some gave pitchers the high strike. Others didn't. The corners were all over the place.

Catchers who could "frame" pitches became more valuable than ever. If you could subtly receive a borderline ball and make it look like a strike, you were worth your weight in gold.

This inconsistency wasn't malicious. Umpires are human. Calling balls and strikes at 95 miles per hour with late movement is incredibly difficult. But the gap between what the rules said and what actually got called created frustration. For players, coaches, and fans.

By the early 2000s, technology started exposing just how inconsistent the zone really was. PITCHf/x tracking systems got installed in every MLB stadium by 2008. They captured the location of every pitch with incredible precision. Suddenly, the data was undeniable. Umpires were missing calls. Lots of them.

Studies showed umpires were calling the zone wider than the rulebook said. Especially on the outer edges. They were also calling it higher than the official definition. Particularly for taller batters. The "shadow zone"—pitches just off the plate that regularly got called strikes—became a documented fact.

The stage was set for the next evolution. And in 2026, that evolution arrived.