When Baseball's Writers Got It Wrong: The 1936 Hall of Fame Ballot Controversy

The greatest collection of baseball talent ever assembled on a single ballot, and somehow the writers managed to screw it up.

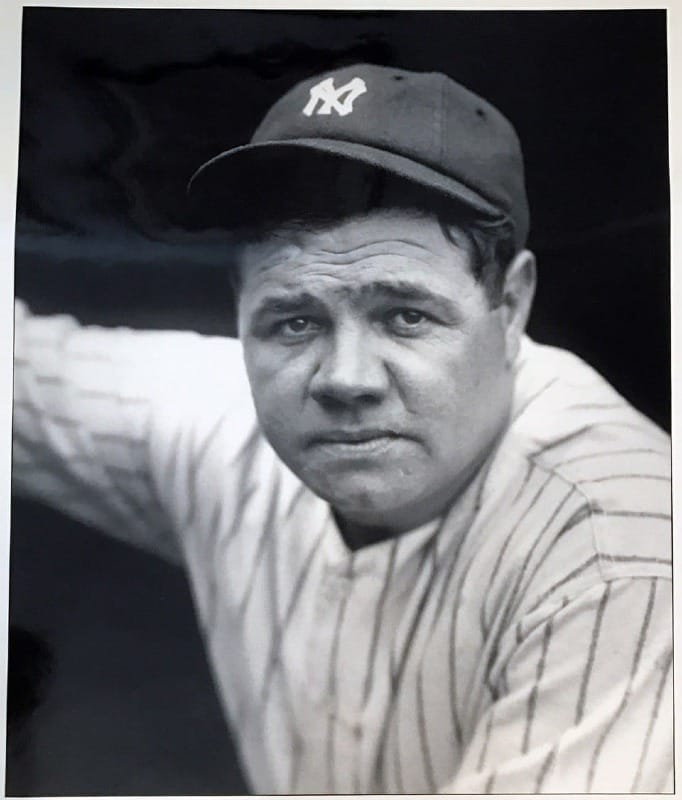

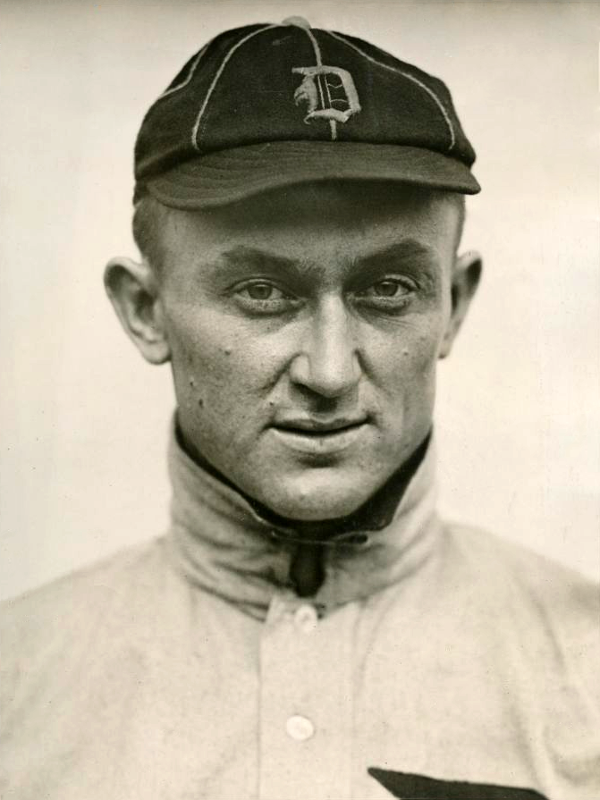

On February 2, 1936, the Baseball Writers' Association of America announced the first five inductees to the brand new Baseball Hall of Fame. Ty Cobb (OF, DET). Babe Ruth (OF, NYY). Honus Wagner (SS, PIT). Christy Mathewson (RHP, NYG). Walter Johnson (RHP, WSH). Five immortals. Five no-brainer selections.

Except the writers couldn't even get that right.

The Ballot That Broke Baseball's Brain

Here's what happened: 226 baseball writers cast ballots. Each could vote for up to 10 players. The threshold for induction was 75%, or 170 votes. Simple enough, right?

Ty Cobb received 222 votes—98.2% of the total. Babe Ruth, the most famous athlete in America, the man who'd transformed baseball from a dead-ball game into the national pastime's modern era, got 215 votes—95.1%. That's 11 ballots that left Ruth off completely.

Four writers looked at Ty Cobb's career and thought, "Nah, not one of the 10 best players in baseball history."

The counting room literally stopped when Ruth's name didn't appear on a ballot. According to newspaper reports, the tabulation committee was "amazed" and paused for a discussion about "how anyone could leave the great Ruth off the list of immortals."

They should've kept counting. It got worse.

The Snubs That Made No Sense

Honus Wagner tied Ruth at 215 votes. Mathewson got 205. Johnson scraped in with 189—just 19 votes above the minimum.

The chaos continued.

Napoleon Lajoie (2B, CLE)—career .338 batting average, revolutionized second base defense, won the Triple Crown in 1901—finished sixth with 146 votes. That's 64.6%. He needed 24 more votes.

Tris Speaker (OF, CLE)—.345 career average (sixth all-time), 792 doubles (still the record), 3,514 hits, greatest defensive center fielder of his generation—got 133 votes. Just 58.8%.

Cy Young (RHP, CLE/BOS)—511 career wins, a record that will never be broken—received 111 votes. Not even 50%.

Let that sink in. Cy Young, the pitcher with the most wins in baseball history by 94 games, couldn't crack 50% on the first Hall of Fame ballot. Today they give an award with his name on it to the best pitcher each year. In 1936, writers looked at 511 wins and thought, "Eh, maybe next year."

Rogers Hornsby (2B, STL), the greatest right-handed hitter who ever lived with a .358 career average, got 105 votes—46.5%. He was still active as a player-manager at the time, which hurt him. But still.

George Sisler (1B, SLB)—.340 career average, 257 hits in 1920 (still the AL record)—received just 77 votes, 34.1%.

Eddie Collins (2B, PHI/CHW)—.333 average, 741 stolen bases, one of the smartest players ever—got 60 votes, 26.5%.

Why Cobb Over Ruth?

Here's where it gets interesting. Why did Cobb receive more votes than Ruth?

The simple answer: baseball writers in 1936 valued different things than we do today.

Cobb represented old-school baseball. Scientific hitting. Manufacturing runs. Playing the game "the right way." He held the all-time hits record (later broken by Pete Rose) and owned a .366 career batting average that still stands as the highest ever. Writers who'd grown up watching dead-ball era baseball saw Cobb as the epitome of baseball excellence.

Ruth? Ruth was a revolutionary, but he was also a drunk, a womanizer, and a guy who broke all the old rules. He swung for the fences when smart baseball said you should slap the ball around. He ate hot dogs and drank beer and lived like there was no tomorrow. Some writers, the older ones especially, saw Ruth as the beginning of baseball's decline, not its savior.

Dan Daniel, writing in the New York World-Telegram on February 4, 1936, disagreed. "Ruth is the standout," he wrote. "Ruth made over baseball, lifted it into the big stadium era, raised the financial plane of the game, attracted to baseball millions who never before had gone into ballparks. And Ruth never made a mistake on the field."

But John Kieran, writing in The New York Times the same day, focused on the mystery of the four voters who left Cobb off entirely. "It remains a mystery that any observer of modern diamond activities could list his version of the 10 outstanding baseball figures and have Ty Cobb nowhere at all in the group."

Neither columnist could figure out what those writers were thinking.

Neither can we.

The Numbers Tell a Different Story

Let's look at what the sabermetrics say about the First Five versus some of the snubs.

The First Five:

- Ty Cobb: 151.4 WAR, .366 BA, .433 OBP, .512 SLG

- Babe Ruth: 162.2 WAR, .342 BA, .474 OBP, .690 SLG (206 OPS+)

- Honus Wagner: 130.9 WAR, .328 BA, .391 OBP, .466 SLG

- Walter Johnson: 164.8 WAR, 417-279 record, 2.17 ERA (147 ERA+)

- Christy Mathewson: 95.2 WAR, 373-188 record, 2.13 ERA (136 ERA+)

Total WAR: 704.5

Some Who Didn't Make It:

- Tris Speaker: 134.4 WAR, .345 BA, .428 OBP, .500 SLG (157 OPS+)

- Cy Young: 163.6 WAR, 511-316 record, 2.63 ERA (138 ERA+)

- Nap Lajoie: 107.4 WAR, .338 BA, .380 OBP, .467 SLG (152 OPS+)

- Rogers Hornsby: 127.0 WAR, .358 BA, .434 OBP, .577 SLG (175 OPS+)

Speaker's 134.4 WAR was higher than Wagner's 130.9. Cy Young's 163.6 WAR beat everyone except Ruth. Hornsby's .358 batting average and 175 OPS+ were both superior to Cobb's numbers.

The writers weren't voting based on WAR, it wouldn't be invented for another 70 years. But even by the standards they did use (batting average, wins, hits), some of these omissions made no sense.

The Confusion Factor

Part of the problem was sheer confusion about what voters were supposed to do.

The original ballot listed 33 suggested names. After complaints that obvious candidates like Ed Delahanty, Willie Keeler, and Cy Young were missing, the BBWAA sent amended ballots with seven more names. This led some voters to think those were the only eligible candidates.

They weren't. Write-ins were allowed.

But some voters didn't know that, so they squeezed their 10 votes into the names on the ballot, leaving deserving write-in candidates off entirely.

Worse, 58 ballots were initially cast as "All-Star teams"—one player at each position. When reminded this was wrong, 10 voters sent back their ballots unchanged, insisting that's how they wanted to vote regardless of instructions.

The Veterans Committee was supposed to handle 19th-century players separately. But the voting rules were so confusing that nobody got elected from that era in 1936. The whole process was a mess.

What This Tells Us About Baseball in 1936

The 1936 vote reveals how baseball viewed its own history.

First, there was a clear bias toward hitters over pitchers. Ruth, Cobb, and Wagner were locks. Johnson and Mathewson barely made it, and Young—with more wins than God—didn't. Baseball had always celebrated hitting more than pitching, and the 1936 vote proved it.

Second, recency bias was real. The writers were mostly older guys who'd grown up watching dead-ball era baseball. Cobb started his career in 1905. Ruth started in 1914. The writers knew Cobb better, respected his old-school approach more, and voted accordingly.

Third, character mattered—or at least, the appearance of character. Ruth's off-field behavior cost him votes. So did Speaker's, probably. In 1926, Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis had investigated allegations that Speaker and Cobb had been involved in fixing a 1919 game. Both were cleared, but the stink lingered. That might explain why four voters left Cobb off entirely.

Fourth, writers had no idea what they were doing. This was the first Hall of Fame election in any sport, ever. There was no blueprint. Some voted for the best players. Some voted for the most important players. Some voted for their childhood heroes. Some voted for guys they'd personally covered. Some tried to build an All-Star team.

The result was chaos disguised as consensus.

The Aftermath: Getting It Right Eventually

The good news? Most of the snubs got corrected quickly.

In 1937, Lajoie (83.6%), Speaker (82.1%), and Young (76.1%) all got elected. Hornsby made it in 1942. Sisler in 1939. Collins in 1939. Mickey Cochrane (C, PHI/DET), who got just 80 votes in 1936, made it in 1947.

Eventually, 40 of the 47 players who received at least one vote in 1936 were inducted into Cooperstown. The writers got it right in the end. They just needed a few tries.

The 1936 ballot also established a precedent that lasted 83 years: nobody was unanimous. Not Ruth. Not Cobb. Not Wagner. Not anyone. Writers seemed to believe that voting for all the obvious candidates was too easy, that leaving someone off proved you were thinking independently.

This ridiculous tradition lasted until 2019, when Mariano Rivera (RHP, NYY) finally became the first unanimous inductee with all 425 votes.

Eighty-three years. That's how long it took baseball writers to admit that some players are so obviously deserving that everyone should vote for them.

What the 1936 Vote Means Today

The Class of 1936 remains the greatest Hall of Fame class in history by total WAR: 704.5. The next closest is the Class of 1939 at 565 WAR.

But the controversy around that first vote established something else: Hall of Fame elections would always be arguments, not conclusions. Every year, deserving players would get left off. Every year, someone would complain. Every year, the standards would shift.

The 1936 ballot had everything—legends getting snubbed, confusion about the rules, debates over character versus performance, old school versus new school. It set the template for every Hall of Fame argument that followed.

Ty Cobb got the most votes because baseball in 1936 still valued his brand of baseball most. Babe Ruth got left off 11 ballots because some writers couldn't forgive him for changing the game. Cy Young didn't crack 50% because pitchers have always been undervalued.

The writers who left Ruth off those 11 ballots were wrong. The writers who left Cobb off four ballots were wrong. The writers who left Speaker, Young, and Lajoie below 75% were wrong.

But they were also human. They were making judgments about players they'd watched, admired, and covered. They didn't have WAR or OPS+ or any objective measure beyond batting average and win totals. They just had their memories and their opinions.

Turns out, that wasn't quite enough.

The Hall of Fame opened its doors on June 12, 1939, in Cooperstown, New York. The living members of the Classes of 1936, 1937, 1938, and 1939 gathered for a photo. Everyone was there except Ty Cobb, who skipped the ceremony.

Even in victory, Cobb stood apart.

Maybe those four writers who left him off the ballot knew something the rest of us missed.

Or maybe they were just as confused as everyone else.