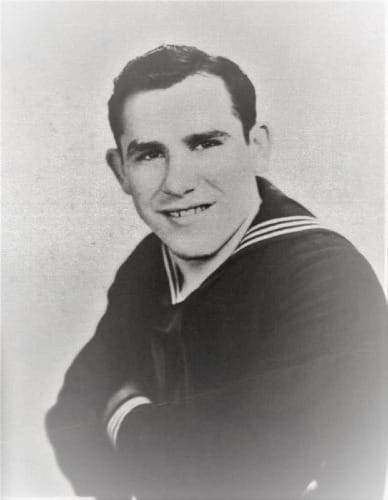

Yogi Berra: The Catcher Who Stormed Normandy

Before Lawrence Peter "Yogi" Berra became one of baseball's beloved figures, before he won 10 World Series rings and three MVP awards, he was a scared 19-year-old kid on a 36-foot rocket boat off the coast of France. It was June 6, 1944. The pre-dawn sky looked like the Fourth of July, he'd later recall, except the fireworks were German machine guns and artillery trying to kill him.

Most fans know Yogi Berra as the stocky catcher who anchored the greatest dynasty in baseball history. But before the championships and the All-Star games, Berra put his baseball dreams on hold to serve his country during World War II.

From The Hill to the Navy

Berra grew up in “The Hill,” an Italian neighborhood of St. Louis. His parents had immigrated from Italy and didn't know much about baseball. Lawrence dropped out of school after eighth grade to help with family finances, working in a shoe factory while playing American Legion ball.

In September 1942, the Yankees offered him a $500 signing bonus—double what the Cardinals had offered. He played 123 games for their Norfolk Tars affiliate in 1943, hitting .259 in the Class B Piedmont League.

Then came January 1943. Berra turned 18. Shortly after, he got word from Uncle Sam to report for his pre-induction physical. He passed. The Navy allowed him to finish the 1943 baseball season before reporting for duty, but his playing days were done for a while.

Berra initially planned to join the Army. But a Navy officer who ran baseball teams at Naval Station Norfolk told him they were losing players and needed a catcher. The pitch worked. Berra enlisted in the U.S. Navy in January 1944, figuring he'd stay clean and maybe even play some ball.

That's not quite how it worked out.

Training for Something Bigger

After basic training at Bainbridge, Maryland, Berra got bored during the winter months. When the Navy asked for volunteers for a "very (secret) mission" involving Landing Craft Support (LCS) (something called rocket boats) boats, Berra raised his hand. He later admitted he had no idea what a rocket boat even was.

In March 1944, he shipped to Little Creek, Virginia, for specialized amphibious training. The Landing Craft Support, Small LCS was a wooden-hulled vessel armed with rockets and machine guns. The boats were designed for one purpose: get close to enemy beaches and unleash hell so the infantry could land with a better chance of survival.

It was dangerous work. These 36-foot boats had six-man crews and no armor. They'd race to within 300 yards of the shore, fire their rockets at German defenses, then use machine guns to suppress enemy positions. German gunners loved targeting them.

In April 1944, Seaman Second Class Berra sailed for the British Isles aboard the USS Bayfield, an attack transport that would serve as the flagship for the Utah Beach invasion. He was assigned as a gunner's mate, manning a twin .50-caliber machine gun turret.

D-Day: June 6, 1944

Around 5:00 AM on D-Day, Berra and his crew were lowered from the Bayfield into the choppy waters of the English Channel. Their mission was straightforward but terrifying: provide covering fire for the troops landing at Utah Beach.

As dawn broke, Berra's boat moved to within 300 yards of the French coastline. The crew unleashed their rockets at German fortifications, then turned their machine guns on enemy positions. Tracers crisscrossed the sky. Explosions lit up the beach. The noise was deafening.

Berra later described himself as "scared stiff" but focused on his job. An officer had to yell at him to keep his head down. The sheer volume of fire was staggering.

After the initial assault, Berra's crew stayed off the coast of France for nearly two weeks. Their duties shifted to patrol work and a grimmer task: retrieving the bodies of fallen soldiers from the water. It was work that haunted Berra for the rest of his life. He rarely spoke about it, embodying the quiet humility of the Greatest Generation.

Operation Dragoon and a Purple Heart He Never Claimed

Two months later, in August 1944, Berra participated in Operation Dragoon, the Allied invasion of southern France. His rocket boat support, where German forces had converted a beachfront hotel into a machine gun nest.

As Berra's crew fired on the position, a German bullet struck him in the left hand. The wound qualified him for a Purple Heart. Berra refused to file the paperwork. He didn't want his mother to receive a telegram saying he'd been wounded. She was already worried enough.

Years later, his family tried to obtain the Purple Heart on his behalf. The effort hit a wall when they discovered Berra's military records had been destroyed in the 1973 fire at the National Personnel Records Center National Arc in St. Louis. The scar on his left hand was the only proof he carried.

Following Operation Dragoon, Berra was stationed in Tunisia, then returned to the United States in January 1945. He was assigned to the Naval Submarine Base in New London, Connecticut, where he played baseball for the base team. He also snuck off base to play for the Cranston, Rhode Island, Chiefs under an assumed name, earning $50 per game.

Berra was honorably discharged in May 1946 as a Seaman Second Class. By September, he was in the big leagues.

The Transition to Baseball Greatness

Berra made his major league debut on September 22, 1946, going 2-for-4 with a two-run homer. He was 21. The kid who'd survived D-Day was about to become a legend.

Those lost years to military service—1944 and 1945—might have cost Berra statistics, but they gave him something else. The discipline. The focus under pressure. The ability to perform when it mattered most. These weren't just baseball skills. They were survival skills he'd learned on a rocket boat off the coast of France.

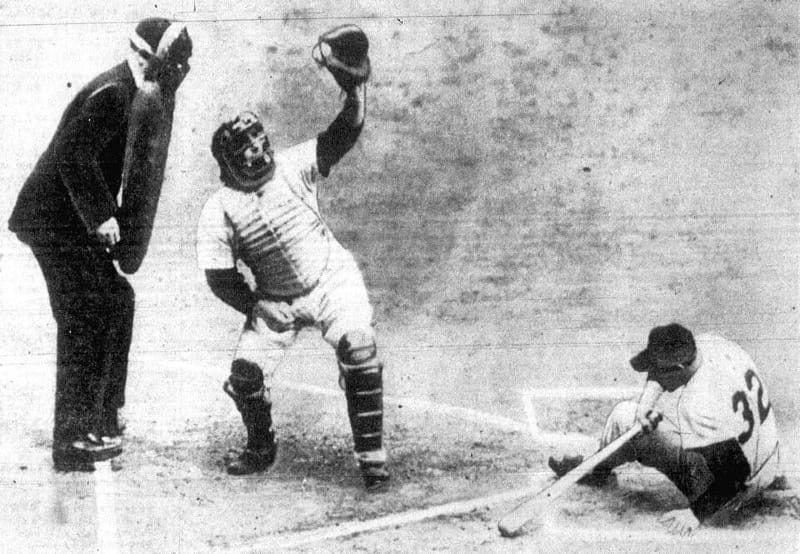

By 1948, Berra was the Yankees' first-string catcher. His career slash line of .285/.348/.482 with a 125 OPS+ is accurate. He hit 358 home runs, drove in 1,430 runs, and posted 59.5 WAR.

His peak years tell the real story. From 1950 to 1956, he was one of the most productive catchers in baseball. He won MVP awards in 1951, 1954, and 1955. In 1950, he hit .322/.383/.533 with 28 homers and 124 RBIs, posting a 135 OPS+.

Berra made 15 All-Star teams. He played in 14 World Series and won 10 of them—more than any other player in baseball history. He caught Don Larsen's perfect game in in the 1956 World Series. He led AL catchers eight times in games caught and six times in double plays.

The Competitive Edge

Behind the plate, Berra was relentless. He wasn't just catching pitches and calling games. He was working batters over with constant chatter, trying to break their concentration.

Hank Aaron learned this the hard way during the 1957 World Series. As Aaron stepped to the plate, Berra noticed something about his grip and mumbled, "Hank, you're holding the bat wrong. You're supposed to hold it so you can read the label."

Aaron didn't even look down. "I didn't come up here to read," he said. "I came up here to hit."

Ted Williams, one of the most focused hitters in baseball history, complained that Berra was the hardest catcher to hit against—not because of his pitch calling, but because of the noise. In one at-bat, Berra asked Williams about his relationship with his manager. Williams had to step out of the box to compose himself. "He was doing it just to agitate me," Williams admitted later. "And it worked."

Berra would ask about players' families during the pitcher's windup. He'd comment on swings and misses. "That was a good pitch to hit, Willie," he'd tell Willie Mays after a swing and miss. "You usually hit those."

The chatter wasn't mean-spirited. It was psychological warfare dressed up as friendly conversation. And it was incredibly effective.

The Harmonica Incident

By 1964, Berra had transitioned to manager. The Yankees were struggling, slumped in third place after a humiliating four-game sweep by the White Sox. The press was already speculating that Berra had lost control of the team.

On August 20, the team bus headed to O'Hare Airport. Utility infielder Phil Linz pulled out a harmonica and started practicing "Mary Had a Little Lamb". The screeching notes grated on everyone's nerves, especially Berra's.

"Knock it off!" Berra shouted from the front of the bus.

Linz didn't hear him clearly. He turned to Mickey Mantle and asked what Yogi had said.

Mantle, always looking for mischief, deadpanned: "He said to play it louder".

Linz did. Berra snapped.

The mild-mannered catcher-turned-manager stormed to the back of the bus and confronted Linz. "I said shove that harmonica!" He slapped it out of Linz's hands. It flew across the bus and hit Joe Pepitone in the knee.

The bus went silent.

The press had a field day. The Yankees fined Linz $200. But something shifted after that incident. The players realized the lovable Yogi had a breaking point. He wasn't just their former teammate. He was the boss.

The Yankees won 22 of their next 28 games and clinched the American League pennant. Linz later joked that he was more famous for the harmonica than his .235 career batting average. He even signed an endorsement deal with Hohner harmonicas.

The Legacy

Berra retired as a player after a brief stint with the Mets in 1965. He managed the Yankees (1964) and the Mets from 1972 to 1975, leading them to the 1973 World Series. He returned to manage the Yankees in 1984-85.

In 2009, the U.S. Navy honored Berra with the Lone Sailor Award. It was one of the few times he publicly discussed his wartime experiences.

In 2015, President Obama awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom (Berra died September 22, 2015), citing his military service and civil rights activism .

Yogi Berra's Hall of Fame plaque calls him "A legendary Yankee." That's true, but it's not the whole story. Before he was a legend, he was a sailor who put his life on the line. Before he caught 173 shutouts and won 10 World Series rings, he was a 19-year-old gunner's mate on a rocket boat, doing his job under fire.

The discipline he learned in the Navy—the focus under pressure, the ability to perform when it mattered most—became the foundation of everything that followed.

Ten rings, one for each finger. Berra was proud of that. But if you asked him what he was proudest of, he might have pointed to the scar on his left hand—the one he got off the coast of France in August 1944.