Baseball's Third Major League: The Rise and Fall of the Federal League

In the winter of 1913, a bunch of businessmen met in Indianapolis and kicked off what would become the biggest challenge to baseball's structure since the American League was formed. The Federal League—just a minor league in 1913—announced it would operate as America's third major league starting in 1914. This bold move would change baseball's landscape, drive player salaries through the roof, and eventually lead to the game's unique antitrust exemption that still exists today.

The Birth of a Challenger

Oil tycoon James A. Gilmore brought both vision and cash when he became the league's president. The 1913 version had just six teams in midwestern cities, but Gilmore and his financial backers wanted much more.

"We're not looking to fight anyone," Gilmore told reporters in December 1913, though his actions suggested otherwise. "We simply believe there's room for another major league that treats players fairly and gives fans quality baseball at reasonable prices."

The timing wasn't random. Baseball was booming in the early 1900s. Fans packed the stands, and profits soared. Yet player salaries barely budged thanks to the reserve clause, which tied players to their teams indefinitely unless traded or released.

The league put teams in eight cities for 1914: Chicago, St. Louis, Pittsburgh, and Indianapolis (competing directly with existing major league teams), plus Baltimore, Buffalo, Kansas City, and Brooklyn. Wealthy industrialists funded these teams, giving the league financial muscle that previous challengers lacked.

Chicago's team, first called the Chi-Feds and later the Whales, had the deepest pockets. Owner Charles Weeghman, who made his fortune in lunch restaurants, built a modern steel and concrete stadium at Clark and Addison Streets—a ballpark we now know as Wrigley Field.

The Brooklyn team attracted Harry F. Sinclair, the oil magnate who would later get caught up in the Teapot Dome scandal. Baltimore's franchise had backing from attorney Ned Hanlon, a former manager who had led the Baltimore Orioles to National League pennants in the 1890s.

This group of wealthy owners gave the Federal League staying power. Unlike earlier "outlaw leagues" that quickly folded, the Federals had enough money to weather losses while building their brand.

The Player Raid Begins

To win over fans, the Federal League needed players people recognized. Despite the reserve clause binding players to their teams, Federal League owners opened their wallets and started aggressively recruiting established stars.

Their first big catch was Joe Tinker, the famous shortstop from the Cubs' championship teams and part of the "Tinker to Evers to Chance" double-play combo. Tinker jumped to the Chicago Federals as player-manager for the 1914 season. The Cubs had traded Tinker to Cincinnati after the 1912 season, and when the Reds tried to send him to Brooklyn, he refused—creating an opening for the Federals.

Other big names soon followed. First baseman Jack Quinn left the Yankees. Pitcher Eddie Plank (P, PHA), who had won 284 games for the Philadelphia Athletics, signed with the St. Louis Terriers. Three-finger Brown (P, CHC), the Cubs' pitching star from the previous decade, joined the Brooklyn Tip-Tops.

Hall of Famer Napoleon Lajoie (2B, CLE) would join in 1915, as would pitching star Chief Bender (P, PHA). The Federals even made serious offers to Ty Cobb (OF, DET) and Tris Speaker (OF, BOS), with contracts that would have doubled their pay.

By opening day 1914, about 80 players with major league experience had signed with Federal League teams. While many were past their prime or marginal talents, enough stars made the jump to give the league credibility.

"These aren't just castoffs," a Baltimore newspaper wrote. "These are legitimate major leaguers who see the Federal League as a better opportunity."

The established leagues initially brushed off the threat. Ban Johnson, the powerful American League president, called the Federal League "a minor league with major league pretensions" and predicted it wouldn't last a single season. National League president John Tener called it "a temporary annoyance."

Their tone changed as player raids continued and salaries shot up. When the Federals targeted Walter Johnson (P, WAS), the Washington Senators' ace, alarm bells rang throughout organized baseball. Johnson signed a three-year contract with the Chicago Federals for $17,500 per year—nearly double his Senators salary.

The Senators' owner, Clark Griffith, personally traveled to Johnson's farm in Kansas to persuade him to reconsider. After intense talks, Johnson returned to Washington with a new contract matching the Federal offer—a massive raise made entirely to prevent his departure.

Similar stories played out across baseball, as teams suddenly found themselves bidding to keep their own players. Ty Cobb's salary jumped from $15,000 to $20,000 when the Detroit Tigers feared losing him to the Federals. Tris Speaker saw his pay increased by the Boston Red Sox for the same reason.

Financial Reality Sets In

Despite decent attendance and competitive play, the Federal League's money problems worsened in 1915. Most teams lost between $80,000 and $120,000 during the season. Even Weeghman's well-backed Chicago franchise lost money.

Several factors caused the mounting losses. Legal costs for fighting organized baseball drained resources. Player salaries, driven up by the bidding war, created huge payroll expenses. And while attendance was okay, it fell short of what teams needed to break even.

By late 1915, some Federal owners started looking for a way out. Organized baseball, also feeling the pinch from the salary wars, became open to settlement talks. Informal negotiations began in October 1915, partly arranged by John Conway Toole, who knew leaders from both sides.

The talks picked up speed in December, with an agreement reached on December 22, 1915. The settlement heavily favored the established leagues:

• The Federal League would shut down immediately

• Chicago owner Weeghman could buy the Chicago Cubs and move them to his Weeghman Park (later Wrigley Field)

• St. Louis owner Phil Ball could buy the St. Louis Browns of the American League

• Brooklyn owner Harry Ward would be allowed to buy a stake in the Brooklyn Dodgers

• The owners of the other five Federal League teams would receive cash payments totaling about $600,000

• All pending lawsuits would be dropped

Notably left out was the Baltimore franchise, owned by Harry Goldman and Ned Hanlon. Their rejection of the settlement terms would have severe consequences down the road.

Legacy and Impact

The Federal League's brief run permanently changed baseball in several important ways:

Player Salaries

The most immediate impact came in player pay. The average major league salary jumped from about $3,000 in 1913 to around $5,000 by 1915—a big increase when $1,000 was a comfortable middle-class yearly income.

Unfortunately for players, this boost didn't last. Once the Federal League threat disappeared, salaries gradually dropped again. By 1918, the average had fallen back to around $3,500. Still, the episode showed that competitive bidding for talent could dramatically increase player compensation—a lesson that stuck around.

Geographical Expansion

The Federal League ventured into markets that the established leagues had ignored, particularly Kansas City and Baltimore. While neither city got a major league team right after the Federal League collapsed, their strong fan support helped make the case for later expansion.

Most concretely, the league left behind two ballparks that would become legendary: Weeghman Park in Chicago (renamed Wrigley Field in 1926) and Federal League Park in Baltimore (later redeveloped as Oriole Park).

The Antitrust Exemption

The most lasting impact came through an unexpected legal channel. The Baltimore franchise owners, excluded from the settlement, filed their own antitrust lawsuit against organized baseball in 1916. The case, Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore v. National League, eventually reached the Supreme Court in 1922.

In a unanimous decision, the Court ruled that baseball was not subject to federal antitrust laws because it was not interstate commerce. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote that baseball games were "purely state affairs" despite teams crossing state lines to play each other.

This ruling gave baseball a unique antitrust exemption that has survived to this day—the only major professional sport with such protection. This exemption gave owners tremendous leverage over players for generations until collective bargaining and arbitration emerged in the 1970s.

The Commissioner's Office

The Federal League war exposed weaknesses in baseball's governance. The three-person National Commission, which had governed the game since 1903, proved ineffective at addressing the Federal League challenge in a unified way.

When baseball owners reformed their governance after the 1919 Black Sox scandal, they created the commissioner's office—a position with broad powers held by a single person. Their first choice? Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, who had so effectively stalled the Federal League's antitrust suit.

The Human Cost

Beyond the business impact, the Federal League's collapse created personal hardships. Players who had jumped to the Federals found themselves blacklisted when they tried to return to organized baseball. Some never played in the majors again despite having good years left in them.

Hal Chase, once considered among baseball's greatest first basemen, saw his career effectively ended after his Federal League stint. Though his reputation was already damaged by gambling connections, his Federal League jump gave teams an excuse to shut him out.

Investors in Federal League teams took big financial hits. Baltimore's investors lost approximately $100,000—about $2.5 million in today's dollars. Many smaller investors lost significant chunks of their life savings.

Conclusion

The Federal League represents a key chapter in baseball's development—a serious challenge to the established order that ultimately failed but left lasting marks on the game's structure, economics, and legal standing.

For just over two years, baseball fans in eight cities experienced a genuine third major league that played competitive baseball, built impressive ballparks, and forced the established powers to take notice. The league's willingness to treat players more fairly helped highlight problems with the reserve clause system, even if permanent reform would take decades more to achieve.

While the Federal League couldn't overcome the financial and legal advantages of organized baseball, it showed that the national pastime's structure wasn't set in stone. The fan interest and investor money that the Federals attracted suggested baseball could support more teams in more cities—a lesson that would eventually lead to expansion in the 1950s and beyond.

"We didn't win the war," James Gilmore said years later, "but we changed how the battle would be fought in the future."

Here is a review of the events that connect the Federal League with the eventual end of the Reserve Clause and Free Agency.

How the Reserve Clause Finally Met Its End

The reserve clause that the Federal League challenged didn't disappear overnight. It actually took another 60 years after the Federals folded before players finally broke free from baseball's form of indentured servitude.

The Long Wait

After the Federal League collapsed in 1915, players had zero leverage. Team owners tightened the reserve clause, ensuring there was no wiggle room for players to negotiate. Salaries stagnated, and players were stuck wherever they landed.

Think about it - for decades, a ballplayer had three options: play for whoever owned your contract, quit baseball entirely, or hold out without getting paid. That was it. No shopping your talents around, no salary negotiations with multiple teams. The choice was to take it or leave it.

Curt Flood Takes a Stand

The first real crack in the system came from an unlikely source. Curt Flood wasn't the biggest star in baseball, but he sure changed it forever.

Flood was a really good center fielder for the Cardinals during the 1960s. He won seven Gold Gloves and hit over .300 six times. After the 1969 season, the Cardinals traded him to Philadelphia. Flood took one look at Philly's terrible old stadium, their losing record, and said, "No thanks."

But here's the thing - players couldn't refuse trades. The Phillies now owned Flood's rights, and that was that. Instead of accepting it, Flood wrote to Commissioner Bowie Kuhn: "I do not feel that I am a piece of property to be bought and sold irrespective of my wishes."

Flood sat out the 1970 season and took baseball to court. His case eventually reached the Supreme Court, where he lost 5-3. The Court basically said, "Yeah, the reserve clause might be unfair, but it's been around so long that Congress, not us, should change it."

Flood sacrificed the rest of his career for the fight. He played just 13 more games in 1971 before retiring. But he'd started something big.

The Loophole Nobody Noticed

The real breakthrough came because of a contract detail almost everybody overlooked.

In 1974, Oakland A's pitcher Jim "Catfish" Hunter discovered the team owner Charlie Finley hadn't made payments to an insurance policy that was part of Hunter's contract. An arbitrator ruled this breached the contract, making Hunter a free agent.

Hunter hit the open market and signed with the Yankees for $3.75 million over five years - an astronomical sum for 1975. This was technically a special case, but it showed what could happen when players negotiated freely.

Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally Change Everything

The final blow came through Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally. Both pitched the 1975 season without signing new contracts. They played under the "renewed" version of their previous contracts.

Here was their argument: The reserve clause let teams renew a player's contract for one year if they couldn't agree on terms. But what happened after that renewed year? Could teams keep renewing forever? Or did players become free after playing one season under a renewed deal?

Arbitrator Peter Seitz sided with the players in December 1975. His ruling said the reserve clause allowed for just ONE renewal, not infinite renewals. After playing that one renewed year, players became free agents.

Baseball owners freaked out. They fired Seitz immediately and tried to overturn the ruling. But the courts upheld it.

Free Agency Is Born

Instead of continuing to fight, owners and players negotiated a new system. Starting in 1976, players could become free agents after six years of major league service. This compromise gave teams control of young players for a reasonable time while giving veterans freedom to sell their services to the highest bidder.

Salaries exploded almost overnight. The average player salary was about $45,000 in 1975. By 1980, it had nearly tripled to $130,000. Today, the minimum wage is 700,000, and the average is around $4 million.

The Federal League Connection

It's incredible how this all connects back to the Federal League. When those rich guys decided to challenge organized baseball in 1913, they gave players a brief taste of what competition for their services could mean.

The Federal League lost its war, but players never forgot the lesson: freedom to negotiate means better pay and conditions. Sixty years later, when Flood, Hunter, Messersmith and McNally finally broke through, they finished what the Federal League started.

James Gilmore's words about changing how the battle would be fought couldn't have been more right. The Federal League planted the seeds, but they took a long, long time to grow.

Up Next: The Lost Dynasty

On Deck: TBA

Rick Wilton | Diamond Echoes

Keeping Baseball's Memories Alive

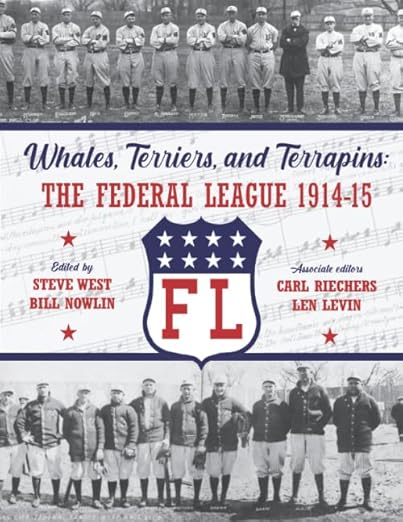

Recommended reading: