Dick Allen - The Long Road to Cooperstown

The phone call finally came on a cold December day in 2020. Dick Allen, one of baseball's most electrifying and misunderstood stars, had been voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame by the Classic Baseball Era Committee. For thousands of fans who had watched his towering home runs and witnessed his battle against prejudice, the news brought tears of joy. For Allen himself, it represented a long-delayed recognition of his brilliance on the baseball diamond.

Sadly, Allen never got to enjoy his enshrinement. He passed away at age 78 in 2020, just 17 days before the announcement. This weekend, as his plaque is officially unveiled in Cooperstown, baseball fans can finally celebrate the career of a man who should have been enshrined decades ago.

"It's about time," says former teammate Mike Schmidt, himself a Hall of Famer. "Dick was the most talented player I ever saw. What he did with a bat in his hands was nothing short of amazing."

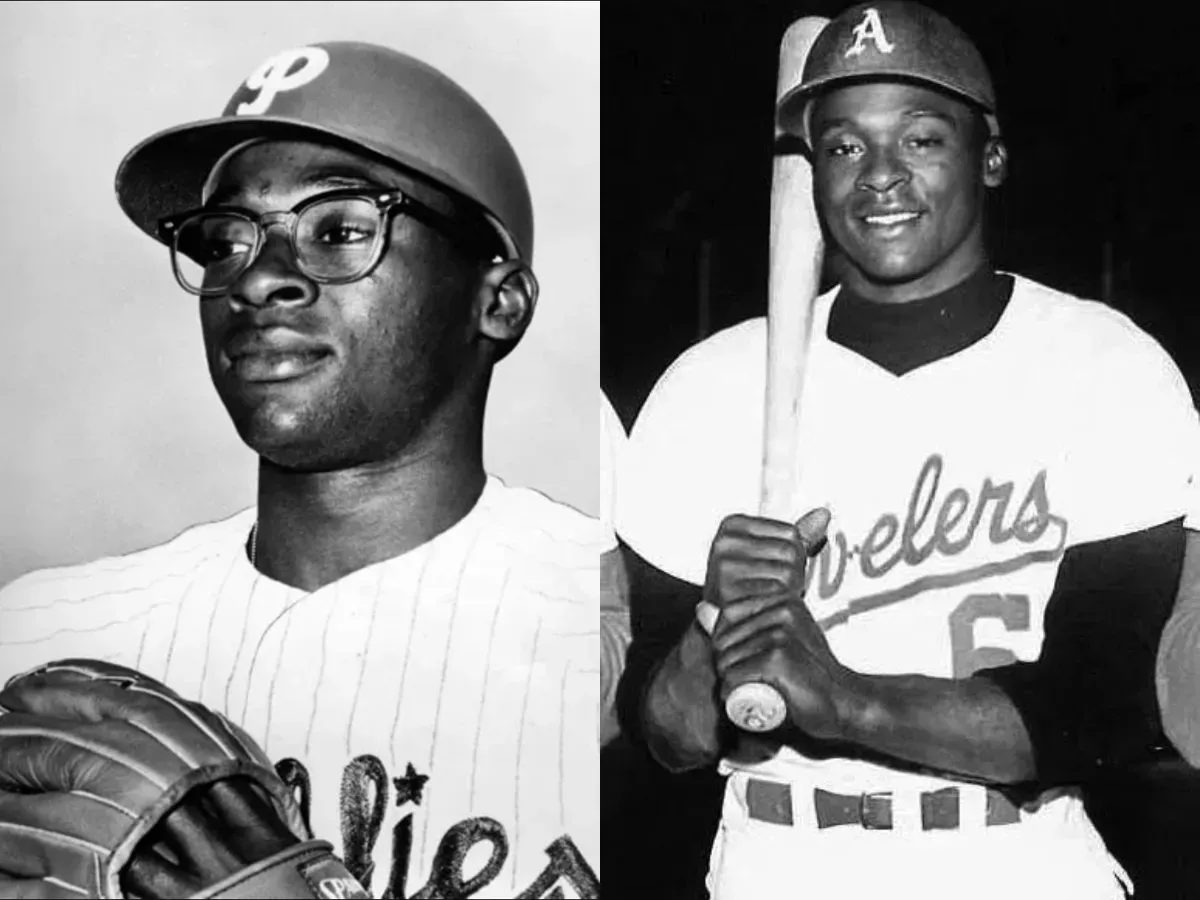

Amazing barely covers it. During his 15-year career with the Phillies, Cardinals, Dodgers, White Sox, and A's, Allen hammered 351 home runs, won the 1964 National League Rookie of the Year award, claimed the 1972 American League MVP, and made seven All-Star teams. His career OPS+ of 156 ranks him among the all-time greats, tied with Willie Mays and Frank Thomas.

But numbers alone can't tell the story of Dick Allen. His path to Cooperstown was paved with obstacles that most players never faced.

Standing Against the Storm

The August sun beat down on Connie Mack Stadium as Dick Allen took the field for pre-game warmups. The 23-year-old star was in the middle of another outstanding season, but that didn't matter to some of the fans who had come to see the Phillies play that Sunday in 1965.

As Allen tossed a ball near third base, the shouts began. First from just one fan, then spreading to a small group behind the dugout. Racial slurs rained down, along with cups and food wrappers.

"Go back to the jungle!" one man yelled, loud enough for everyone nearby to hear.

Allen's teammate Johnny Callison saw his jaw tighten. The older outfielder jogged over, putting a hand on Allen's shoulder.

"Just ignore them, Richie," Callison said. "They're not worth it."

Allen nodded but said nothing. This wasn't new. Since arriving in Philadelphia, he'd faced this treatment almost daily. Little Rock had been worse – death threats slipped under his hotel door, letters warning him not to take the field – but Philadelphia was supposed to be different. This was the big leagues, the major leagues.

As Allen walked back toward the dugout, a beer bottle crashed at his feet, sending glass and foam spraying across his cleats. The crowd noise swelled – some cheering the bottle thrower, others shouting at him to stop.

Inside the dugout, Phillies manager Gene Mauch was fuming. He grabbed Allen by the arm.

"You want me to pull you from the lineup?" Mauch asked. "No one would blame you."

Allen looked back at the stands, then down at his bat waiting on the rack. The same 40-ounce piece of lumber that had already hit 15 home runs that season.

"No," Allen said firmly. "That's what they want. I'm playing."

Hours later, with the Phillies trailing by a run in the eighth inning, Allen strode to the plate with two runners on base. The same fans who had hurled insults now held their breath. Allen dug in, his powerful wrists flexing around the bat handle.

The pitcher's offering came in belt-high. Allen's swing was a blur of controlled violence. The crack echoed throughout the stadium as the ball soared toward the light towers in left field, eventually landing 440 feet from home plate. A three-run homer.

As Allen rounded the bases, the stadium erupted – even those who had taunted him couldn't help but cheer the sheer athletic brilliance they had just witnessed. Allen touched home plate with his head down, accepted a few high-fives from teammates, and took his seat in the dugout without expression.

After the game, a reporter asked about the home run and the earlier incidents. Allen simply said: "I let the bat do my talking."

And it spoke volumes. For every slur, every bottle, every booing fan, Allen answered with excellence. It was his way of fighting back – not with his fists or his words, but with his extraordinary talent. It wouldn't change everyone's mind, but for that day at least, even his harshest critics had to acknowledge his greatness.

Years later, reflecting on those difficult early seasons, Allen would say: "Baseball was fun, but it wasn't always fun in Philadelphia. Still, I wouldn't change it. Those hard times made me stronger."

The Right Man at the Wrong Time

When Richie Allen (as he was first known) joined the Philadelphia Phillies in 1963, he stepped into a powder keg. The Phillies were the last National League team to integrate, and Philadelphia was a city with deep racial divisions.

At just 21 years old, Allen found himself cast as an unwilling pioneer. Before reaching the majors, he spent the 1963 season with the Phillies' Triple-A team in Little Rock, Arkansas, becoming one of the first Black players in the International League. There, he faced constant threats, hate mail, and shouts from the stands that no young man should ever hear.

His manager, Frank Lucchesi, later recalled: "I saw things happen to that kid that would've broken most men. But Dick just kept hitting the ball a mile and holding his head high."

When Allen reached Philadelphia in 1964, things hardly improved. The city's north side was experiencing racial tensions, and Allen became a lightning rod for criticism. Fans booed him mercilessly, writers questioned his character, and the Phillies organization did little to protect their young star.

In response, Allen developed a tough exterior. He started wearing a batting helmet in the field after fans threw batteries and other objects at him. He scrawled messages in the dirt around his position. He showed up late to games. The media painted him as a troublemaker, when in reality, he was a young Black man trying to survive in a hostile environment.

"They said I was troublesome," Allen once said. "All I wanted was to be treated like a man."

Chicago Renaissance: The Tanner Effect

Allen's relationship with teammates transformed in Chicago, largely due to manager Chuck Tanner's approach. Tanner, unlike previous managers, treated Allen like an adult, giving him freedom rather than imposing rigid rules.

"Chuck would say, 'Dick, just be in the batter's box when it's your turn to hit,'" recalls White Sox pitcher Wilbur Wood. "And Dick respected that trust. He was always there when it mattered."

Allen flourished, winning the 1972 AL MVP award and becoming a team leader. He took young players like Goose Gossage and Terry Forster under his wing, teaching them about pitching to tough hitters.

"Dick saved my career," Gossage has stated repeatedly. "He taught me how to set up hitters, how to use my fastball more effectively. I might not have made it without his help."

In Chicago, Allen also formed a close friendship with teammate Bill Melton. The two were inseparable, often arriving at the park together and taking extra batting practice.

"We called them Batman and Robin," laughs former White Sox outfielder Pat Kelly. "Where you saw one, you'd find the other."

Road Trip Generosity

On the road, Allen was known for taking rookies under his wing, particularly in cities known for being unwelcoming to Black players.

"My first road trip to Atlanta in 1973, I was one of only a few Black players on the team," recalls White Sox outfielder Ken Henderson. "Dick made sure I knew which areas of town to avoid, which restaurants would serve us without hassle, and he never let me eat alone. He'd been through it all before and wanted to make it easier for me."

Allen frequently paid for team meals on the road and organized card games in his hotel room, creating team bonding opportunities. Despite his reputation as a loner, former teammates describe him as surprisingly social in comfortable settings.

"Dick's hotel room was like the team clubhouse after games," says White Sox pitcher Jim Kaat. "He'd order food for everyone, turn on music, and just create this relaxed space where guys could unwind. He paid for everything and never made a big deal about it."

The Christmas Connection

One of Allen's most consistent but least-known habits was remembering teammates' children at Christmas. For years after his retirement, he sent gifts to the families of players he'd been close with.

"Every December like clockwork, packages would arrive for my kids," says Tony Taylor, Allen's teammate from the 1960s Phillies. "Even 10 years after we played together, Dick never forgot them at Christmas. That's not something you do for publicity – the media never knew about it. That's just who he was."

Former White Sox catcher Ed Herrmann shared a similar experience: "My son was born in December 1972. Every year until he was 18, Dick sent him a birthday/Christmas gift. We moved three times, but Dick always found our address. My son never met him, but Dick never forgot him."

The Ultimate Gift: His Time

Perhaps Allen's greatest generosity was giving his time and attention – particularly remarkable given his desire for privacy.

When Phillies infielder John Vukovich was diagnosed with cancer in the mid-2000s, Allen visited him regularly, sitting quietly for hours providing companionship during treatments.

"Dick would drive two hours each way just to sit with Vuk during chemo," says Larry Bowa. "No publicity, no fanfare. He'd bring lunch, sometimes a chess board, and just be there. That's real friendship."

Similarly, when White Sox teammate Bill Melton suffered a serious back injury that threatened his career in 1972, Allen visited his home almost daily during rehabilitation.

"I was in a back brace, depressed about my career possibly being over," Melton remembers. "Dick would come by, bring dinner for my family, watch games with me, and just keep my spirits up. He didn't have to do any of that."

The Lasting Impact

The full extent of Allen's generosity may never be known. Many teammates have taken personal stories to their graves, while others learned only years later that Allen was behind anonymous acts of kindness.

What's clear is that the public image of Dick Allen as selfish or isolated from teammates couldn't be further from the truth. The real Allen was thoughtful, generous, and deeply loyal to those who earned his trust.

"The Dick Allen I knew for over 45 years wasn't just a great baseball player," Mike Schmidt said at Allen's memorial service. "He was one of the most generous men I've ever known. Not with grand gestures for attention, but with small, meaningful acts that changed lives when it mattered most."

Perhaps that's the most fitting tribute to Allen's character – not that he gave, but how he gave: quietly, personally, and without seeking credit or publicity. For a man so often misunderstood by the public, his teammates knew the truth.

As Goose Gossage put it: "Some guys are generous because they want everyone to know it. Dick was generous because that's just who he was. And if you were lucky enough to be his teammate, you saw the real man behind the headlines."

Teaching the Game

Beyond material generosity, Allen gave freely of his baseball knowledge. As one of the game's great hitters, his advice was invaluable, and he shared it willingly.

Greg Luzinski, who would become a Phillies slugger, was a raw rookie when Allen returned to Philadelphia in 1975. "I was swinging at everything, trying to pull everything for power," Luzinski says. "Dick spent hours teaching me pitch recognition. He'd call out what was coming based on the pitcher's grip or delivery – 'Fastball in!' or 'Slider away!' – and he was almost always right. He taught me how to read pitchers."

With the White Sox, Allen worked extensively with young hitter Jorge Orta on hitting breaking pitches. Their sessions often stretched long after teammates had left the ballpark.

"Dick wouldn't just say 'do this' or 'do that,'" Orta explains. "He'd break down exactly why certain adjustments worked. He was like a hitting professor who could also hit 500-foot home runs."

Weight Training Validation

While Allen didn't use formal weight training (it wasn't common in baseball then), his natural strength and physically demanding off-season work demonstrated what was possible with superior strength.

"Dick was built differently," says former Phillies trainer Larry Odenthal. "His forearms were like Popeye's. He didn't lift weights like players do today, but he worked hard labor jobs in the off-season – construction, farm work – and it gave him functional strength nobody else had."

Allen's success helped change attitudes about strength training for baseball players, which was still viewed with suspicion in the 1960s and early 1970s.

The Legend Grows

As years pass, Allen's power feats have taken on an almost mythical quality. Like Babe Ruth's "called shot" or Mickey Mantle's 565-foot homer at Washington's Griffith Stadium, some skeptics question whether Allen's longest blasts really went as far as reported.

What separates Allen's power legacy from mere baseball tall tales is the consistency of testimony from reliable witnesses – Hall of Fame players, respected managers, and objective journalists who saw the same displays of raw power across different ballparks and years.

Willie Mays, who witnessed baseball's greatest sluggers across four decades, put it simply: "Dick Allen could hit a baseball further than anyone I ever saw."

For a man often defined by controversy and misunderstanding, Allen's power was the one aspect of his game that was never in dispute. Even his harshest critics acknowledged that when it came to raw hitting ability, few if any could match what Dick Allen could do with a bat in his hands.

As baseball grows increasingly scientific, with launch angles and exit velocities measured to decimal points, there remains something magical about Allen's natural power – an elemental force that, to those who witnessed it firsthand, represented baseball power in its purest form.

The Comeback to Philadelphia

After years away, Allen returned to Philadelphia in 1975. The city that once booed him now cheered his every move. The young hothead was now a respected veteran, and fans who had grown up had gained perspective on his early struggles.

"I wasn't different when I came back," Allen said. "They were different."

In his first game back at Veterans Stadium, Allen received a standing ovation that lasted nearly two minutes. He tipped his helmet – the same helmet he once wore in the field for protection – to acknowledge the cheers.

Though his skills had diminished with age and injuries, Allen still had moments of brilliance in his second Philadelphia stint. He retired after the 1977 season, finishing with career numbers that deserved Hall of Fame consideration: 351 home runs, 1,119 RBIs, a .292 batting average, and a .912 OPS.

But the writers didn't see it that way. His highest vote percentage was just 18.9%, and he fell off the ballot after receiving less than 5% in 1997. The narrative of Allen as a troublemaker had stuck, overshadowing his on-field brilliance.

This table summarizes Allen's case by showing his rankings among all MLB players during his active years (1963-1977) in key offensive categories, compared to the average Hall of Fame first or third baseman.

Dick Allen's Hall of Fame Credentials - Statistical Summary

| Category | Allen's Rank (1963-1977) |

Value | HOF Average (1B/3B) |

|---|---|---|---|

| OPS+ | 1st | 156 | 138 |

| ISO | 2nd | .242 | .210 |

| wRC+ | 1st | 155 | 138 |

| SLG | 3rd | .534 | .490 |

| OBP | 6th | .378 | .362 |

| MVP Shares | 7th | 2.38 | 1.92 |

| Offensive WAR | 8th | 69.9 | 60.3 |

| WAR/650 PA | 9th | 5.2 | 4.6 |

This table summarizes Allen's case by showing his rankings among all MLB players during his active years (1963-1977) in key offensive categories, compared to the average Hall of Fame first or third baseman.

Allen led all of baseball in OPS+ and wRC+ during this 15-year period, ranking ahead of Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, Frank Robinson, and every other hitter of his generation. His isolated power trailed only Harmon Killebrew during this span.

In every key offensive category, Allen exceeded the average Hall of Fame corner infielder, often by substantial margins. His OPS+ was 18 points higher, his ISO was 32 points higher, and his offensive WAR was nearly 10 wins greater than the average Hall of Famer at his position.

The Statistical Verdict

The numbers make a compelling case for Dick Allen's Hall of Fame worthiness. When measured by rate statistics, he ranks alongside inner-circle Hall of Famers like Mays, Aaron, and Robinson. His peak performance from 1964-1974 represents one of the most dominant offensive stretches in baseball history.

Allen's relatively short career (1,749 games) and defensive limitations explain why his career WAR (58.7) falls below some Hall of Fame standards. However, when considering his performance in context – playing in pitcher-friendly parks during a pitcher-dominated era, while facing significant off-field challenges – his offensive brilliance becomes even more remarkable.

As baseball historian Bill James noted: "Dick Allen was more of an impact player offensively than anyone else in the game when he played." The statistical record supports this assessment and confirms that Allen's plaque in Cooperstown is well deserved.

Keeping Baseball's Memories Alive

Rick Wilton | Diamond Echos