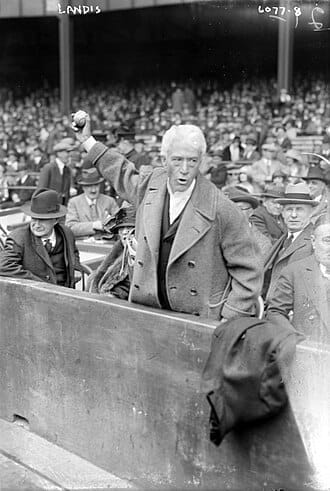

Kenesaw Mountain Landis: Baseball's Iron-Fisted First Commissioner

Kenesaw Mountain Landis

The judge had a name as unusual as his methods were severe. Kenesaw Mountain Landis ran baseball like he ran his courtroom. Absolute authority. Zero tolerance for anything he considered a threat to the game. For nearly 25 years, from 1920 until his death in 1944, Landis wielded more power over America's pastime than any commissioner before or since.

His father had been wounded at the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain during the Civil War. He named his son after it, dropping one "n" in the spelling. Born November 20, 1866, in Millville, Ohio, Landis stood just 5-foot-6 and weighed about 130 pounds. But his presence filled every room he entered. Players and owners alike feared being summoned to his Chicago office.

From Federal Judge to Baseball's Czar

President Theodore Roosevelt appointed Landis as a United States District Judge for the Northern District of Illinois in March 1905. He quickly made a national name for himself. In 1907, Landis slapped Standard Oil Company with a $29 million fine for antitrust violations. It was the largest fine in American history at that time. The decision was later overturned on appeal, but Landis had cemented his reputation as a trust-busting judge unafraid of powerful interests.

Baseball came calling in 1915. The upstart Federal League sued Major League Baseball under antitrust laws. The Federal League claimed organized baseball had monopolized the business of baseball exhibitions in violation of the Sherman Act. The case landed on Landis' docket. He was a Cubs fan who attended games and paid for his own tickets. During the trial, Landis declared from the bench that "any blows at baseball would be regarded by this court as a blow to a national institution."

Then he did something remarkable.

Nothing.

Landis never ruled on the case. He let it sit on his docket until the end of 1915 when the Federal League collapsed and the parties reached a settlement. When the Baltimore franchise later sued and the case reached the Supreme Court in 1922, the Court ruled that baseball was not interstate commerce. Therefore it wasn't subject to federal antitrust laws. This decision gave baseball its famous antitrust exemption, which remains controversial to this day.

Years later, Landis admitted he had delayed the decision. He would have been forced to rule against baseball, which would have severely damaged the sport he loved. Baseball's owners never forgot how Landis had protected them. When they needed someone to restore the game's integrity after the 1919 World Series scandal, they knew exactly who to call.

The Black Sox and Baseball's Darkest Hour

The 1919 World Series nearly destroyed baseball. Eight Chicago White Sox players were accused of conspiring with gambler Arnold Rothstein to throw the Series to the Cincinnati Reds. Fans were outraged. The game's integrity was in tatters. Baseball needed someone with an iron fist to clean up the mess.

On January 12, 1921, Landis was elected baseball's first commissioner. He insisted on keeping his federal judgeship while serving as commissioner. This led to an impeachment effort in Congress and censure from the American Bar Association. But Landis didn't care about critics. He agreed to take the job on one condition: his baseball salary of $50,000 would be reduced by the $7,500 he received as a judge.

His first major act set the tone for everything that followed. The eight Black Sox players were acquitted in court (after key evidence mysteriously disappeared). Landis banned all eight from baseball for life anyway. He declared: "Regardless of the verdict of juries, no player that throws a ball game, no player that entertains proposals or promises to throw a game, no player that sits in a conference with a bunch of crooked players and gamblers where the ways and means of throwing games are discussed, and does not promptly tell his club about it, will ever again play professional baseball."

The banned players pleaded for reinstatement over the years. Landis never wavered.

He wasn't done cleaning house, either. He also banned New York Giants outfielder Benny Kauff for theft in 1921. Giants pitcher Phil Douglas got the boot in 1922 for suggesting he would leave the club to help them lose the pennant. Several others connected to gambling followed. Players learned quickly that gambling on baseball was a career-ending decision under Landis.

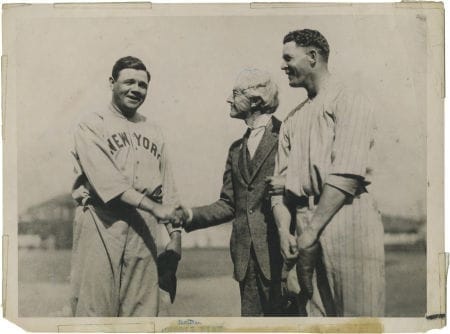

Babe Ruth Learns Who's Boss

Even the biggest star in baseball couldn't defy Judge Landis and get away with it.

After the 1921 World Series, Babe Ruth had just completed his best season to date. He batted .378 with 59 home runs and 171 RBI. He and teammates Bob Meusel and Bill Piercy decided to go on a barnstorming tour across the Northeast. There was just one problem: Section 8B of Article 4 of the Major League code, which took effect in February 1921, forbade World Series participants from playing exhibition games during the year the championship was decided.

Landis had warned Ruth not to do it. According to one account, when Ruth heard Landis meant to enforce the rule, he reportedly said, "Tell the old guy to go jump in the lake."

Ruth went ahead with the tour anyway. He played games in Buffalo, Elmira, and Scranton. After a barnstorming game in Elmira on October 17, 1921, Ruth said, "I am not in any fight to see who is the greatest man in baseball." He argued that players from second and third-place teams were allowed to barnstorm. So why not him? Ruth believed he was doing something good for baseball by giving fans a chance to see big-league players.

Landis waited until December to drop the hammer. He fined Ruth and Meusel their full World Series shares of $3,500 each. He suspended them for the first six weeks of the 1922 season—39 games total. The suspension meant Ruth missed Opening Day and didn't return until May 20, 1922.

The impact was immediate and measurable. Fans bought fewer than half the tickets to Yankees games at home and on the road in April and May of 1922 compared to 1921. Baseball needed Babe Ruth. But Landis had made his point: nobody was above the rules, not even the Sultan of Swat.

Ruth signed a three-year contract in early 1922 for $52,000 a year. That was more than three times what the next highest-paid Yankee earned. That extra $2,000, according to legend, was decided by a coin flip because Ruth liked making a thousand dollars a week. When he finally returned to the lineup, 40,000 fans welcomed him back to the Polo Grounds.

By July 1922, the barnstorming rule was changed. World Series players now needed to get consent from their club president and permission from the commissioner before joining tours. This eventually led to the famous barnstorming tours of Ruth and Lou Gehrig in the mid-1920s, with the Bustin' Babes facing the Larrupin' Lous.

The War Against Branch Rickey's Farm System

Branch Rickey was building something revolutionary in St. Louis. Landis hated it.

In 1919, Rickey purchased an 18 percent stake in the Houston Buffaloes of the Texas League. Then he acquired interests in players in two minor leagues and several other teams. His vision was clear: create an assembly line of young talent in the minor leagues that the Cardinals could develop without risk of losing them to other major league clubs. The farm system was born.

Landis opposed the whole concept. He believed it damaged baseball by blocking players from advancing to the majors. Players disparagingly called the farm system the "chain gang." To prevent players from stagnating in the minors, Landis implemented a policy allowing major league clubs to draft players who spent two consecutive seasons on one minor league team.

The Cardinals kept finding ways around Landis' policies. When the commissioner discovered the Cardinals owned affiliates in Dayton and Fort Wayne that played in the same league, he declared future Hall of Famer Chuck Klein a free agent.

Things came to a head in March 1938. On March 23, 1938, Landis opened an investigation into the Cardinals and their minor league system. He found they were blocking players from reaching the majors. Players would only be called up when a major leaguer retired. This created a logjam in the minors.

Landis freed 74 Cardinals farmhands from six minor league teams. He fined the owners of these teams a total of $2,176. The fines included $1,000 against Springfield, $588 against Cedar Rapids, and $580 against Sacramento. Only one released player, Jimmy Webb, received an invite to the Cardinals for a tryout. Most players simply re-signed with their former clubs, minimizing the practical impact.

Cardinals owner Sam Breadon sympathized with the released players. But he also defended Rickey, stating: "Rickey should be praised as the savior of the minor leagues through his development of the farm systems which has had, as everyone knows, the constant opposition of the Commissioner's office."

The irony is that Landis lost this war. Every other major league team copied the Cardinals' model. By 1940, the Cardinals had 32 affiliates. Only the New York Yankees (14) and Brooklyn Dodgers (18) had more than 10. The farm system became standard practice across baseball and remains so today. Rickey's vision, not Landis' opposition, shaped the future of player development.

The Unbreakable Color Barrier

This is the darkest chapter of Landis' legacy.

For his entire tenure as commissioner, from 1920 to 1944, baseball remained completely segregated. The Negro National League was founded in 1920 by Rube Foster. It operated independently outside of Organized Baseball. Black players, no matter how talented, were barred from the major leagues.

Landis maintained a public position that there was no rule preventing teams from signing Black players. He stated: "Negroes are not barred from organized baseball by the commissioner…there is no rule in organized baseball prohibiting their participation and never has been to my knowledge." He claimed signing Black players was the business of club owners. The commissioner's job, he said, was to interpret and enforce the rules.

This was technically true but practically meaningless. Landis had engineered and maintained a 1923 agreement outlawing interracial play. In 1923, Negro National League president Rube Foster proposed a series of games between the best Negro League and Major League teams. Landis responded by banning white major league teams from playing exhibition games against Black teams.

When integration advocates pushed for change, Landis stonewalled them. In 1942, ten leaders of progressive unions attended the annual meeting of baseball owners to demand teams recruit Black players. Landis refused to meet with them.

In December 1943, pressure finally forced Landis to act. Paul Robeson and several Black newspaper publishers met with Landis and the team owners to appeal for breaking the color line. Fans across the country wrote to Landis urging him to end segregation. A telegram from postal employees in College Station, Texas, said: "If Negroes are good enough to appear in the casualty lists, they are good enough to appear in the box score."

At the meeting, Landis reiterated there was no written rule against signing Black players. But he took no action to encourage integration. He declared that integration was a matter for the teams to decide, not the league. Baseball's color line remained in place for nearly four more years.

In 1943, Bill Veeck attempted to purchase the Philadelphia Phillies. He planned to stock the team with Negro League All-Stars including Satchel Paige. Landis blocked the purchase after learning of Veeck's intentions.

Landis died on November 25, 1944, at St. Luke's Hospital in Chicago. It was eight days after being elected to a new seven-year term. His death removed a major barrier for integration advocates. His successor, Happy Chandler, had a different perspective. When Branch Rickey signed Jackie Robinson to the Dodgers organization in 1945, Chandler overruled the owners' fifteen-to-one vote against Rickey. This allowed Robinson to begin his career in professional baseball in the spring of 1946.

Robinson broke the major league color barrier on April 15, 1947. Less than three years after Landis' death. In 2020, the Baseball Writers' Association of America voted to remove Landis' name from the Most Valuable Player Award, citing his "failure to integrate the game during his tenure."

The Complex Legacy

Two weeks after his death, Landis was voted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame by a special committee. His plaque credits his integrity and leadership with establishing baseball in the esteem and affection of the American people.

That's only part of the story. Landis saved baseball after the Black Sox scandal. He restored public confidence in the game when it desperately needed credibility. His suspensions and bans sent a clear message: baseball would police itself severely and honestly. No player, not even Babe Ruth, was above the rules.

But he also used his power to maintain baseball's shameful segregation. He fought against innovations like the farm system that became standard practice. His autocratic style left little room for disagreement or dissent.

American League president Will Harridge said of Landis: "He was a wonderful man. His great qualities and downright simplicity impressed themselves deeply on all who knew him." His first biographer wrote that Landis may have been arbitrary and unfair. But he "called 'em as he saw 'em" and turned over to his successor a game cleansed of the corruption that followed World War I.

History remembers Landis as both savior and barrier. He had the power to change baseball for the better, and sometimes he did. Other times, he used that same power to resist changes that would have made the game more just and competitive. The white-haired judge with the mountain for a name left baseball stronger in some ways and weaker in others.

That's the complicated truth about Kenesaw Mountain Landis. A man who wielded absolute power over America's pastime and used it both wisely and poorly, depending on what day you asked him.