The Bat That Built Baseball: How Louisville Slugger Shaped America's Pastime

On a sunny afternoon in 1884, a 17-year-old apprentice named John "Bud" Hillerich did what teenagers have done since time began. He skipped work to watch a baseball game.

That decision changed baseball forever.

Bud Hillerich's father, J. Frederick Hillerich, had emigrated from Germany to Louisville, Kentucky in 1856. By 1864, he operated a successful woodworking shop called J.F. Hillerich Job Turning. The business made bed posts, stair railings, bowling pins, and the elder Hillerich's pride and joy: a patented swinging butter churn. Baseball bats were not part of the plan.

But Bud loved baseball. He played amateur ball and crafted bats for himself and his teammates on his father's lathes. When he slipped away from the shop that afternoon to watch the Louisville Eclipse play, he had no idea he was about to launch an industry.

One Broken Bat, Three Hits, A Legend

Pete Browning was one of baseball's brightest stars in 1884. Known as "The Louisville Slugger" and "The Old Gladiator," he would finish his career with a .341 batting average, third-best of his era. But on this particular day, Browning broke his bat during the game.

This was a crisis. Browning had particular ideas about his bats. He named them. He talked to them. Some players thought he was superstitious. Others just thought he was eccentric. Either way, losing a favorite bat mattered to Pete Browning.

After the game ended, Bud Hillerich approached his idol. He offered to make Browning a new bat that very night at his father's shop. Browning agreed and accompanied the teenager to the First Street workshop.

They worked through the night. Browning selected a piece of white ash. Multiple times, Bud removed the bat from the lathe so Browning could test the feel. More shaping. Another test swing. Finally, Pete pronounced it "just right."

The next day, Browning went three-for-three with his new bat.

Word spread fast. Browning's teammates flooded to the Hillerich shop, all wanting custom bats. The baseball bat business had arrived, whether J. Frederick Hillerich wanted it or not.

Note: There is some debate among historians about the exact details of this story. Some accounts place different dates or circumstances around the first bat. But the core truth remains: Bud Hillerich made a bat for Pete Browning in 1884, Browning loved it, and Louisville Slugger was born.

Butter Churns vs. Baseball Bats

J. Frederick Hillerich hated the whole idea. He didn't like baseball. He didn't think there was money in baseball bats. The future of the family business, he insisted, lay in that beautiful swinging butter churn he had patented. For years in the 1880s, he actually turned away professional ballplayers who came seeking custom bats.

Bud persisted. He saw what his father couldn't: baseball was growing, and players wanted better equipment. The bats sold under the name "Falls City Slugger" at first, but in 1894, when Bud took over the family business, he registered a new trademark with the United States Patent Office.

"Louisville Slugger."

The name honored Pete Browning's nickname and the city where it all began. More importantly, it sounded like what it was: serious, professional, powerful.

By 1897, Bud joined his father as a full partner. The company name changed to J.F. Hillerich & Son. The bat business grew steadily, but it still needed something to push it over the top.

The Deal That Changed Sports Marketing Forever

In 1905, Hillerich & Son made history again.

Honus Wagner, the Pittsburgh Pirates shortstop known as "The Flying Dutchman," signed a contract giving the company permission to use his autograph on Louisville Slugger bats. Wagner became the first professional athlete ever to endorse an athletic product.

Think about that. Before Wagner, no player endorsed a bat. No athlete endorsed anything. The entire concept of sports marketing didn't exist in any formal sense. Wagner's deal with Louisville Slugger created the template that every athlete endorsement follows to this day.

The business impact was immediate. Players wanted the same bats their heroes used. Fans wanted bats with their favorite player's signature. Louisville Slugger began producing pattern bats, made to each player's specifications and stamped with their signature. Those formulas went into company vaults for future production.

By 1911, the company recognized another gap. The Hillerichs knew how to make bats, but they lacked professional sales and marketing expertise. Frank Bradsby, a successful salesman for one of the company's largest buyers, joined J.F. Hillerich & Son. His timing was perfect.

The Golden Age of Louisville Slugger

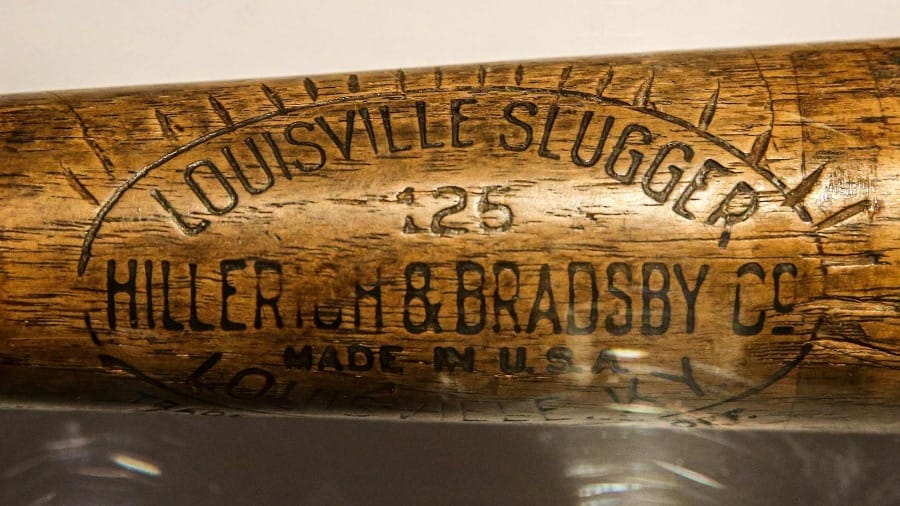

In 1916, Bradsby became a full partner. The company name changed for the last time to Hillerich & Bradsby Co. (H&B). What happened next transformed Louisville Slugger from a regional success into a national icon.

By 1923, H&B was selling more bats than any other bat maker in the country. The reason? Every legendary player swung a Louisville Slugger.

Ty Cobb used them. Lou Gehrig used them. And most famously, Babe Ruth used them.

Ruth's bats became the stuff of legend. His model number, R-43, represented power in its purest form. During the early 1920s, Ruth swung bats weighing between 42 and 44 ounces. Some reports claim he used a 54-ounce bat early in his career. For comparison, Hank Aaron's bat measured 35 inches and weighed just 33 ounces. Ruth's bats were 36 inches long and weighed 9 to 11 ounces more.

No modern player swings anything close to Ruth's lumber. Today's players prefer bats three ounces lighter than their length. Ruth swung bats that were heavier than they were long. He called them his "war clubs."

In 1927, when Ruth hit his record-setting 60 home runs, he began carving small notches on his bats to commemorate each blast. One surviving bat features 28 notches around the Louisville Slugger brand. Ruth later explained it started as a joke, but it served a practical purpose: his teammates stopped borrowing his bats.

Ruth's success with Louisville Slugger cemented the brand's dominance. If the greatest slugger in baseball history trusted Louisville Slugger, why would anyone use anything else?

Through War and Flood

The company's commitment to baseball was tested repeatedly through the 1930s and 1940s. In 1937, a disastrous flood along the Ohio River hit Louisville hard. H&B's factory suffered significant damage. Frank Bradsby worked almost nonstop for weeks to repair the facility and save the business.

Bradsby died later that year. He had no heirs, but the Hillerich family kept his name in honor of his contributions. That's why it's still called Hillerich & Bradsby today.

During World War I and World War II, the company redirected production to support the war effort. They made M-1 carbine gunstocks, track pins for tanks, and billy clubs for the armed forces. But they also continued making baseball and softball bats for the troops. The wars marked the first time women worked in the H&B factory.

After World War II, baseball roared back as America's pastime. Louisville Slugger dominated as the bat of choice for baseball's greatest players. Joe DiMaggio, Ted Williams, Jackie Robinson, Roberto Clemente, Hank Aaron, George Brett, Ken Griffey Jr., Derek Jeter. Generations of legends swung Louisville Sluggers.

The company meticulously tracked every professional player's bat orders. Those records, still housed at the Louisville Slugger Museum, provide a detailed history of how players liked their bats. Weight, length, barrel diameter, handle thickness, finish. Every detail was recorded and duplicated when players reordered their favorites.

The Aluminum Challenge

In 1970, Louisville Slugger faced its biggest competitive threat. Aluminum bats were approved for Little League play. In 1975, they were approved for college baseball.

H&B resisted at first. The company believed replacing wood with aluminum would detract from baseball's traditional character. But by 1978, the market reality was clear: aluminum dominated amateur baseball.

H&B bought the California manufacturer that had been producing aluminum bats on contract and entered the market seriously. The delay cost them. Competitors had established market share, and Louisville Slugger spent years playing catch-up in aluminum.

The wood bat business shrank dramatically outside the major leagues. By the early 1970s, H&B needed more space and moved its operations to a 56-acre facility in Jeffersonville, Indiana, just across the Ohio River. They called it "Slugger Park."

But something was lost in the move. Louisville Slugger belonged in Louisville. In 1996, the company moved back across the river to a new headquarters at 800 West Main Street, just seven blocks from J. Frederick Hillerich's original carpentry shop.

The new complex included the Louisville Slugger Museum & Factory, complete with a 120-foot-tall bat outside, visible for blocks. More than four million people have toured the museum and factory, watching bats being made the same way Bud Hillerich made Pete Browning's bat in 1884.

The Modern Era: Success and Challenges

In 1997, Louisville Slugger achieved what seemed like the ultimate validation. Major League Baseball named it the Official Bat of Major League Baseball. The partnership allowed Louisville Slugger to use the MLB trademark on bats and showcase them during the All-Star Game, Home Run Derby, and World Series.

But the baseball equipment business was changing. Larger multinational companies with deeper resources entered the market. Competition intensified.

In 2015, Hillerich & Bradsby made a difficult decision. They sold the Louisville Slugger brand to Wilson Sporting Goods. The Hillerich family retained ownership of the museum and factory, and H&B continues to manufacture Louisville Slugger bats. But the brand itself now belongs to Wilson.

John A. Hillerich IV, the current president and CEO, and the great-grandson of Bud Hillerich, explained the decision simply: The company could no longer compete with larger multinational competitors that had more resources.

Then came 2025. After 28 years as baseball's official bat, Louisville Slugger lost the designation. Marucci Bats became the new Official Bat of Major League Baseball.

It marked the end of an era, though Louisville Slugger remains hugely popular among MLB players and throughout amateur baseball.

The Legacy in Numbers

Since 1884, Louisville Slugger has sold more than 100 million bats. The company still produces about 1.8 million wood bats annually. For more than 140 years, the crack of a Louisville Slugger hitting a baseball has been one of summer's most recognizable sounds.

The bats are still made primarily from Northern white ash, though that tradition faces challenges. The emerald ash borer, an invasive insect first detected in Michigan in 2002, has destroyed vast sections of North America's ash forests. H&B now uses more maple and birch to compensate for the declining ash supply.

The company that J. Frederick Hillerich thought should focus on butter churns instead became one of baseball's most enduring brands. Four generations of Hillerichs have run the company. The name Louisville Slugger appears on awards for top power hitters at high school and college levels. The Silver Slugger Award recognizes Major League Baseball's best offensive performers at each position.

More Than Just a Bat

Louisville Slugger's influence extends beyond statistics and sales figures. The bats represent connection across generations. Fathers who watched Mickey Mantle gave their sons Louisville Sluggers. Those sons gave Louisville Sluggers to their children who watched Derek Jeter.

The company's museum displays bats used in some of baseball's greatest moments. Bats that hit record-breaking home runs. Bats that won World Series championships. Bats that belonged to legends who are now in Cooperstown.

Each bat tells a story. That's what Bud Hillerich understood when he made Pete Browning's bat in 1884. Baseball isn't just about statistics. It's about the connection between player and equipment, between past and present, between a kid watching a game and dreaming of becoming a star.

J. Frederick Hillerich never saw the potential in baseball bats. He died in 1924, long before Louisville Slugger became synonymous with baseball itself. But his son saw it. Bud Hillerich chose baseball over butter churns, and that choice echoes every time a hitter steps to the plate with a Louisville Slugger.

From one broken bat in 1884 to 100 million bats sold worldwide, Louisville Slugger defined the sound of baseball for more than a century. That 17-year-old apprentice who skipped work to watch a ballgame built more than a company. He built a piece of American culture that will endure as long as someone swings a bat and dreams of hitting a home run.