The Cubs Dynasty: The Greatest Team You've Never Heard About [pt 1]

Origins of the Cubs (1876-1900)

Baseball in Chicago runs deep. Way before the ivy on the walls at Wrigley Field, the team we now know as the Cubs started building something special.

They weren't always the Cubs, though. When the National League formed in 1876, Chicago jumped in as the White Stockings. Later, they became the Colts, then briefly the Orphans. The "Cubs" nickname didn't stick officially until 1907 -- right when they were setting the baseball world on fire.

Adrian "Cap" Anson (1B/MGR, CHC) was the original face of Chicago baseball. A towering figure at 6'0" and 227 pounds (massive for the 1880s), Anson led Chicago to early dominance. His teams grabbed 6 of the National League's first 11 championships between 1876 and 1886.

"Cap ran that team like a military outfit," baseball historian Lawrence Ritter once noted. "The players either shaped up or shipped out."

Those early championships set expectations in Chicago. Fans grew used to winning. But by the turn of the century, the glory days seemed behind them. Little did anyone know, the best was yet to come.

Building the Dynasty (1900-1905)

The groundwork for the Cubs dynasty began with a key hiring: Frank Selee as manager in 1902. Selee, a future Hall of Famer, had a knack for spotting talent and building cohesive teams.

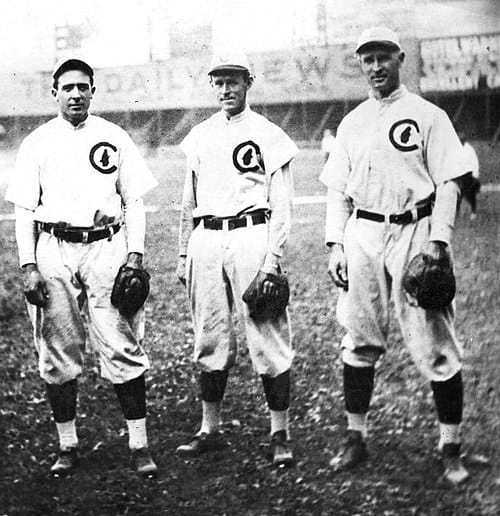

His biggest achievement? Assembling the infield that would soon become legendary. He converted Frank Chance (1B, CHC) from catcher to first base. He brought in Johnny Evers (2B, CHC) to play second. Joe Tinker (SS, CHC) was already at shortstop. Harry Steinfeldt (3B, CHC) would later complete the infield at third base.

By 1905, Selee's health forced him to step down. Frank Chance took over as player-manager, and the pieces were in place for something special.

"Chance wasn't just a great player," teammate Johnny Kling said years later. "He managed with his fists sometimes. Nobody dared cross him."

Under Chance's leadership, the Cubs developed an aggressive, scientific approach to the game. They practiced extensively, perfected defensive positioning, and mastered the hit-and-run. Baseball was changing, and the Cubs were at the front of that change.

The 1906 Juggernaut

The 1906 Cubs were flat-out ridiculous. They won 116 games and lost just 36 for a .763 winning percentage. Over a century later, it remains the highest winning percentage for any modern major league team. Just stop and think about that for a minute.

Their pitching staff was untouchable, posting a team ERA of 1.76 (for comparison, the league average was 2.66). Their team ERA+ of 149 meant they were roughly 49% better than the average pitching staff.

The offense wasn't too shabby either. While not loaded with power (just 20 home runs as a team), they got on base consistently and ran aggressively, stealing 283 bases.

Four players hit over .300, led by third baseman Harry Steinfeldt's .327 average. Frank Chance hit .319 with 103 runs scored and 57 stolen bases. They simply overwhelmed opponents from April through September.

"We didn't think we could lose," Chance said after the season. "We expected to win every day."

The 1906 World Series: Baseball's Greatest Upset

The 1906 World Series stands as perhaps the most stunning upset in baseball history, a David versus Goliath matchup that defied all expectations. This all-Chicago affair pitted the dominant Cubs against their crosstown rivals, the White Sox, in what became known as the "Streetcar Series" since fans could travel between ballparks using the city's public transportation.

The Overwhelming Favorites

The Cubs entered the Series looking nearly unbeatable. Their 116-36 record (.763 winning percentage) remains the best in modern major league history. Led by player-manager Frank Chance, they outscored opponents by an astounding 323 runs during the regular season. Their pitching staff posted a collective 1.76 ERA—nearly two full runs better than the league average.

The starting rotation featured three 20-game winners: Mordecai "Three Finger" Brown (RHP, CHC) (26-6, 1.04 ERA), Jack Pfiester (LHP, CHC) (20-8, 1.51 ERA), and Ed Reulbach (RHP, CHC) (19-4, 1.65 ERA). Brown's nickname came from a childhood farming accident that mangled his right hand, creating an unusual grip that produced one of baseball's most devastating curveballs.

Offensively, the Cubs weren't quite as dominant in the Dead Ball Era context, but still led the National League in runs scored. Frank Chance hit .319 and stole 57 bases, while third baseman Harry Steinfeldt led the team with 83 RBIs. They played an aggressive style featuring hit-and-runs, stolen bases, and squeeze plays that manufactured runs with machine-like efficiency.

Newspapers across the country viewed the Cubs as prohibitive favorites. The Chicago Tribune declared them "practically invincible," while the New York Times called them "the most formidable baseball machine ever assembled."

The Hitless Wonders

In stark contrast stood the Chicago White Sox, nicknamed the "Hitless Wonders" due to their anemic .230 team batting average—dead last in the American League. They had finished the season 93-58, an impressive record overshadowed by the Cubs' historic campaign.

The White Sox roster lacked stars but featured solid pitching and spectacular defense. Their best player was probably shortstop George Davis (SS, CWS), a future Hall of Famer nearing the end of his career. Nick Altrock (LHP, CWS)(20-13, 2.06 ERA) and Ed Walsh (RHP, CWS)(17-13, 1.88 ERA) anchored a pitching staff that kept them competitive despite the offensive struggles.

White Sox manager Fielder Jones employed a style focused on pitching, defense, and small ball tactics—similar to the Cubs but with considerably less talent at his disposal. Before the Series began, Jones boldly predicted: "We're going to surprise some people."

Few took him seriously. Oddsmakers installed the Cubs as 2-to-1 favorites, with some offering even longer odds against the White Sox.

The Series Unfolds

Game 1: The First Shock

The Series opened at the Cubs' West Side Grounds on October 9, with a crowd of over 12,000 fans expecting to see the National League champions assert their dominance. Cubs ace Mordecai Brown took the mound against Nick Altrock.

What happened next stunned the baseball world. The White Sox jumped on Brown early, scoring two runs in the first inning. The Cubs appeared tight, committing uncharacteristic errors. Altrock pitched brilliantly, limiting the mighty Cubs to just four hits. The final score: White Sox 2, Cubs 1.

A Chicago newspaper headline the next day read: "CUBS LOSE! IS IT POSSIBLE?"

Game 2: Order Restored?

The Cubs bounced back in Game 2 behind Ed Reulbach's masterful pitching. He threw a one-hit shutout, and the Cubs prevailed 7-1. This appeared to restore order, with many observers suggesting Game 1 had merely been opening-day jitters for the favored Cubs.

Game 3: South Side Surge

The Series shifted to South Side Park for Game 3. In front of their home crowd, the White Sox once again silenced the Cubs' bats. Ed Walsh, who would later become famous for his spitball, struck out 12 Cubs while allowing just two hits. The Sox won 3-0, taking a surprising 2-1 series lead.

Game 4: The Tables Turn

The Cubs again showed their resilience in Game 4, with Mordecai Brown redeeming himself by throwing a two-hit shutout. The 1-0 victory evened the Series at two games apiece.

Game 5: The Decisive Blow

Game 5 became the turning point. After falling behind 1-0, the White Sox scored three runs in the third inning, aided by Cubs errors. This 3-1 victory gave the Sox a 3-2 Series lead and pushed the mighty Cubs to the brink of elimination.

Game 6: The Unthinkable Happens

On October 14, the teams returned to West Side Grounds for Game 6. The Cubs needed a win to force a decisive Game 7. Instead, the White Sox completed their improbable triumph with an 8-3 victory. The "Hitless Wonders" had beaten baseball's greatest team four games to two.

How Did It Happen?

The upset remains remarkable over a century later. Several factors contributed to the shocking result:

- Defensive Collapse: The Cubs committed 12 errors in the six games, many at crucial moments. This uncharacteristic fielding breakdown from a team known for defensive excellence proved costly.

- Offensive Failure: The mighty Cubs hit just .196 in the Series. Frank Chance, normally reliable, batted .150 without an extra-base hit. The pressure of being overwhelming favorites appeared to affect their hitting approach.

- Strategic Advantages: White Sox manager Fielder Jones employed defensive shifts based on Cubs hitters' tendencies—an innovative approach for 1906. He also exploited the Cubs' aggressive baserunning by calling for pitchouts at key moments.

- Pitching Brilliance: Ed Walsh and Nick Altrock pitched beyond their regular-season performance levels. Walsh's spitball proved particularly effective against Cubs hitters who hadn't faced him during the regular season.

- Psychological Factors: The Cubs may have suffered from overconfidence, while the White Sox played with the freedom of having nothing to lose. As Mordecai Brown later admitted: "We thought we had only to show up to win."

The Aftermath and LegacyThe shocking upset provided the first hint that postseason baseball didn't always follow regular-season patterns. It established the concept that shorter series could produce unexpected results—a principle that remains central to baseball's playoff structure today.

For the Cubs, the loss proved motivational. They returned to win the next two World Series in 1907 and 1908, cementing their dynasty despite the 1906 stumble. Frank Chance reportedly kept newspaper clippings about the upset in the clubhouse as motivation throughout those championship seasons.

For the White Sox, the victory brought tremendous pride but no dynasty. They remained competitive but didn't return to the World Series until 1917 (which they won).

Chicago fans still debate which feat was more impressive—the Cubs' 116 regular-season wins or the White Sox's stunning upset. The crosstown rivalry gained considerable intensity from this Series, establishing a competitive dynamic that continues to this day.

Fielder Jones: The Innovative Manager Behind Baseball's Greatest Upset

Fielder Jones doesn't receive the same historical recognition as contemporaries like John McGraw or Connie Mack, but his innovative approach to managing the 1906 White Sox reveals him as one of baseball's most forward-thinking strategists. His methods helped the "Hitless Wonders" overcome their offensive limitations and topple the mighty Cubs in the World Series.

Defensive Positioning Innovations

Jones' most significant innovation came through his approach to defensive positioning. While rudimentary defensive shifts existed before 1906, Jones implemented them with unprecedented precision and consistency.

According to baseball researcher David Nemec, Jones kept detailed notes on Cubs hitters' tendencies from the few interleague exhibition games played during that era. During the 1906 World Series, he positioned his fielders differently for each Cubs batter—a revolutionary concept at the time.

For Frank Chance, known for hitting to the opposite field, Jones shifted his outfield significantly toward right field. Against Johnny Evers, who frequently bunted, Jones positioned his third baseman unusually shallow. For power hitter Frank Schulte (LHP, CHC), he employed what we'd now recognize as an early version of the "Ted Williams shift," with his second baseman playing deeper and shifted toward first base.

White Sox catcher Billy Sullivan(C, CWS) later recalled: "Fielder knew where every Cubs hitter was likely to hit the ball before they even swung. He'd signal us with subtle hand movements where to play for each batter. The Cubs kept hitting right to where we were standing."

Pitcher Utilization Strategies

Jones broke from conventional wisdom regarding pitcher usage. In an era when managers typically used their best pitchers until they tired, Jones employed what resembled a modern pitching strategy:

- Specialized Roles: He used Ed Walsh primarily as what we'd now call a "stopper" in crucial situations rather than strictly adhering to a rotation. Walsh appeared in three of the six World Series games, something virtually unheard of in 1906.

- Matchup-Based Decisions: Jones studied which types of pitchers gave certain Cubs hitters trouble. He started Doc White (LHP, CWS) in Game 3 specifically because White's pitching style—a combination of off-speed pitches—had previously frustrated Joe Tinker and Johnny Evers.

- Quick Hooks: Jones didn't hesitate to remove struggling pitchers, even though the common practice was to let starters finish games. In Game 6, he pulled Nick Altrock after just four innings despite Altrock having pitched a complete game earlier in the Series.

Part 2 Will Be Published on Thursday July 24, 2025