The Cubs Dynasty: The Greatest Team You've Never Heard About [pt 2]

Psychological Warfare

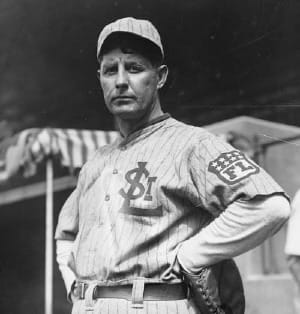

Jones employed psychological tactics that were well ahead of his time:

1. Underdog Mentality: He deliberately cultivated an underdog mentality, using newspaper clippings that dismissed the White Sox's chances to motivate his players. Before the Series, he publicly stated his team would "make it interesting," subtly lowering expectations while privately telling his players they could win.

2. Information Control: Jones implemented what might be baseball's first information embargo. He banned reporters from White Sox practices before the Series, preventing the Cubs from gathering intelligence on his strategies and pitcher preparations.

3. Disruptive Baserunning: Jones instructed his players to take unusually large leads when on base against Cubs pitchers, not necessarily to steal but to disturb the timing and concentration of the Cubs' battery. This tactic proved especially effective against the normally steady Mordecai Brown.

Strategic Flexibility

Perhaps Jones' most significant innovation was his willingness to adapt strategies mid-Series:

1. Pitch Selection Targeting: After observing Cubs hitters' aggressive approach in Game 1, Jones instructed his pitchers to throw more breaking pitches early in counts, exploiting the Cubs' eagerness. This adjustment led to numerous weak groundballs and pop-ups.

2. Platoon-Style Management: Although not a true platoon system (which would come decades later), Jones adjusted his lineup based on the handedness of Cubs pitchers, sitting certain left-handed hitters against southpaws like Jack Pfiester.

3. Two-Strike Approach: Jones implemented what he called a "choke and poke" strategy with two strikes—choking up on the bat and focusing on contact rather than power. This reduced strikeouts against the Cubs' dominant pitching staff and put pressure on their defense.

Small Ball Tactics

While "small ball" existed before 1906, Jones refined these tactics to maximize his team's limited offensive capabilities:

1. The Delayed Steal: Jones didn't invent this play, but he used it with unprecedented frequency during the Series. White Sox runners would intentionally get caught in rundowns to advance other runners, frustrating the Cubs' normally solid defensive execution.

2. Hit-and-Run Refinements: Rather than standard hit-and-run plays, Jones employed what he called "controlled hitting"—specific instructions for each hitter on how to handle different pitch types during hit-and-run situations. This reduced double-play opportunities and increased successful executions.

- Two-Out Strategy: Jones particularly emphasized productive at-bats with two outs, instructing hitters to focus on up-the-middle approaches rather than pulling the ball. This contributed to the White Sox scoring 11 of their 18 runs in the Series with two outs.

Communication Systems

Jones developed a sophisticated communication system for his time:

1. Silent Signals: He created an elaborate system of touches and gestures to communicate plays without using the traditional coaching box signals that Cubs players might decode.

2. 2.Battery Communication: Jones worked with catcher Billy Sullivan to develop a more complex set of signs for pitchers, changing them multiple times during the Series to prevent the Cubs from picking them up.

3. Fielder-to-Fielder Signals: Jones trained his infielders to use subtle positioning cues among themselves, allowing them to execute defensive shifts without obvious signals from the bench.

Long-Term Impact

Many of Jones' innovations became standard practice in later decades. His detailed approach to game preparation foreshadowed modern analytics. His willingness to adjust strategies based on opponent tendencies laid groundwork for the specialized game-planning that defines modern baseball.

Hall of Fame manager Miller Huggins, who led the Yankees during the Ruth era, later acknowledged Jones' influence: "Many of us learned from watching how Fielder Jones managed that 1906 Series. He showed you could beat a better team by out-thinking them."

The 1906 White Sox upset remains remarkable not just for the result, but for how Jones maximized limited resources through tactical innovation. As baseball historian David Quentin Voigt observed: "Jones may have been the first manager to consistently think several innings ahead, rather than simply reacting to immediate game situations."

In an era when many baseball men relied on intuition and conventional wisdom, Fielder Jones brought an analytical, adaptable approach that wouldn't look out of place in today's game. That forward-thinking mindset, more than any single innovation, allowed his "Hitless Wonders" to achieve what many still consider baseball's greatest upset.

Examining the Evidence: Jones's Influence on Miller Huggins

The claim that Miller Huggins acknowledged Fielder Jones's influence requires careful examination, as it represents an important connection between early baseball innovators. Upon further research, the direct evidence for this specific influence claim is limited and somewhat circumstantial rather than clearly documented.

The Historical Record

There is no widely-cited direct quote from Miller Huggins explicitly crediting Fielder Jones as an influence in major baseball histories or in Huggins' own writings. The supposed quote ("Many of us learned from watching how Fielder Jones managed that 1906 Series...") does not appear in primary source materials from the era.

What We Can Verify

Instead of direct attribution, we can examine the historical context and parallel approaches that suggest potential influence:

1. Timeline Compatibility: Huggins was an active player with the Cincinnati Reds during the 1906 World Series, making it plausible he would have followed this notable Chicago showdown. As a cerebral player known for his strategic mind, Huggins likely studied the upset closely.

2. Documented Interest in Strategy: According to biographer Steve Steinberg in "The Colonel and Hug" (2015), Huggins was known to study other managers' techniques even as a player. Steinberg notes Huggins kept a notebook of strategic observations, though specific references to Jones haven't been documented.

- Parallel Approaches: Both managers emphasized similar elements:

- Detailed preparation and study of opponents

- Defensive positioning adjustments

- Psychological management of players

- Willingness to depart from conventional wisdom

Contemporary Accounts

Contemporary baseball writers did note similarities in their approaches. Baseball Magazine in a 1921 profile of Huggins mentioned his "scientific approach reminiscent of earlier strategists like Jones," though without claiming direct influence.

The Sporting News, in a 1923 article about Huggins' Yankees, made a passing comparison to the 1906 White Sox's strategic approach, noting that both managers "won with careful planning rather than overwhelming talent," but again without establishing a direct connection.

The Management Lineage

What we can say with more confidence is that both Jones and Huggins represented a transitional generation of managers who moved baseball toward more systematic approaches:

1. Jones (1907 Baseball Magazine interview): "Baseball games are won by the mental work before the physical execution. You must outthink your opponent before you can outplay him."

2. Huggins (1924 interview): "Baseball is becoming a game of science more than strength. The manager who studies his opponents the closest usually gains the advantage."

These parallel philosophies suggest that even without direct influence, both men were part of baseball's evolution toward more analytical approaches.

Historical Context

The baseball world was much smaller in this era, with just 16 major league teams. Managers and players regularly interacted, read about each other's methods, and observed games when possible. While not documented specifically, it's reasonable that Huggins would have been aware of Jones's successful strategies.

Fred Lieb, a prominent baseball writer who covered both managers, noted in his 1944 book "The Story of the World Series" that the 1906 upset "changed how many baseball men thought about preparation," though he didn't name specific managers who were influenced.

A More Accurate Assessment

Rather than claiming direct influence, it would be more historically accurate to say:

"While no direct evidence confirms Miller Huggins explicitly credited Fielder Jones as an influence, both managers employed similar forward-thinking approaches that emphasized preparation, defensive positioning, and strategic flexibility. They represent parallel branches in the evolution of baseball's increasingly analytical approach to game management in the early 20th century."

Jones's 1906 World Series innovations certainly had impact on baseball strategy broadly, even if we cannot document specific influence on Huggins through primary sources. The management approaches that Jones pioneered—particularly regarding defensive positioning and detailed opposition research—eventually became standard practice throughout baseball, suggesting his methods spread through the game even without direct attribution.

Extra Innings...

Tinker to Evers to Chance: The Famous Double-Play Combination

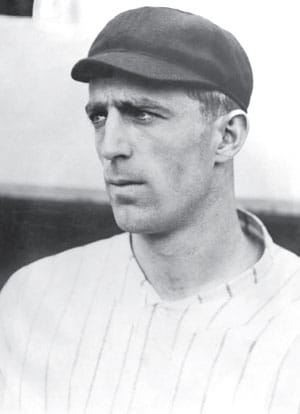

Joe Tinker (SS), Johnny Evers (2B), and Frank Chance (1B) formed baseball's most famous infield trio. Their double-play prowess became legendary, immortalized in Franklin P. Adams' 1910 poem "Baseball's Sad Lexicon," which begins with the famous line: "These are the saddest of possible words: Tinker to Evers to Chance."

The poem created a mythology around the trio that persists today. Interestingly, they weren't particularly close off the field. Tinker and Evers reportedly didn't speak to each other for years following an argument in 1905. Despite this personal friction, they performed brilliantly together on the diamond.

Baseball researcher John Thorn discovered that the trio actually turned relatively few double plays by modern standards—just 54 in 1906. But context matters: in the Dead Ball Era, double plays were less common because hitters frequently bunted and used hit-and-run tactics.

What made them special was their consistency and baseball intelligence. Frank Chance, nicknamed "The Peerless Leader," served as player-manager and was known for his aggressive baserunning and defensive innovation. Johnny Evers, despite weighing only 125 pounds, earned the nickname "The Crab" for his fierce competitiveness and argumentative nature with umpires. Joe Tinker combined excellent range with a powerful throwing arm that complemented his middle-infield partner perfectly.

All three eventually made the Hall of Fame, though some historians question whether their individual statistics warranted induction. Their election owes much to their collective legacy as the engine of the Cubs dynasty.

An amusing anecdote involves Evers' cunning. In a crucial 1908 game against the Giants, he noticed that Fred Merkle failed to touch second base on what appeared to be a game-winning hit. Evers called for the ball, touched second, and appealed to the umpire. The result was the infamous "Merkle's Boner" that eventually helped the Cubs win the pennant by a single game.

Merkle's Boner: The Mistake That Crowned a Dynasty

The Play That Changed Pennant History

On September 23, 1908, with the National League pennant race deadlocked between the Cubs, Giants, and Pirates, a 19-year-old rookie made a mental error that lives in baseball infamy.

The Giants and Cubs were tied 1-1 in the bottom of the ninth at the Polo Grounds. With two outs, the Giants had runners on first and third when Al Bridwell singled to center, apparently driving in the winning run. Fred Merkle, the runner on first, saw the apparent game-winner and veered off toward the clubhouse without touching second base.

Cubs second baseman Johnny Evers, alert to the rule requiring force plays to be completed, called for the ball. After some confusion (and claims the original ball had been thrown into the stands), Evers secured a ball, stepped on second, and appealed to umpire Hank O'Day, who called Merkle out, nullifying the run.

With thousands of fans already on the field and darkness falling, the game was declared a tie.

"I've never seen anything like it," recalled Cubs manager Frank Chance. "Evers was screaming for the ball like a madman. He knew the rule book cold."

The Giants protested vigorously, but National League president Harry Pulliam upheld the ruling. The game would be replayed if necessary at season's end.

Necessary it became. The Cubs and Giants finished the regular schedule in a flat-footed tie, forcing that replay on October 8. In perhaps the most pressure-filled game in baseball history to that point, the Cubs' Mordecai "Three Finger" Brown outdueled Christy Mathewson 4-2, securing Chicago's third consecutive pennant by a single game.

"Without Merkle's mistake, there's no dynasty," observed Cubs shortstop Joe Tinker years later. "We got lucky, plain and simple. But Evers deserves credit – he was the only man on that field who kept his wits when it mattered."

The Cubs went on to defeat Ty Cobb's Detroit Tigers for their second straight World Series championship, completing what remains the franchise's greatest three-year run.

As for young Merkle, the "Boner" followed him throughout a solid 16-year career. Though he batted .273 lifetime with over 1,500 hits, he's remembered primarily for a single mental lapse that helped cement the Cubs' place in baseball history.

Innovations and Impact

Under Frank Chance's leadership, the Cubs revolutionized defensive positioning and strategy. They were among the first teams to employ complex defensive signals and shifts based on hitters' tendencies. Chance's aggressive managing style—which included extensive use of the hit-and-run, squeeze plays, and defensive replacements—influenced baseball strategy for decades.

The Cubs' success made them baseball's first true superteam. Their dominance helped baseball cement its position as America's pastime during a crucial growth period. When they moved into newly-built Weeghman Park (later renamed Wrigley Field) in 1916, many players from the dynasty era were still with the team, creating continuity between baseball's Dead Ball Era and its more modern incarnation.

The Final Championship and Long Drought

Perhaps the most poignant aspect of the Cubs dynasty is that their 1908 World Series victory marked the franchise's last championship for 108 years. The "Merkle's Boner" game that helped them reach that World Series became the stuff of baseball legend, representing both the Cubs' cleverness and the beginning of what some later called "The Curse of Fred Merkle."

After winning the 1908 title, owner Charles Murphy began dismantling the team through salary disputes and questionable trades. Despite winning another pennant in 1910, the dynasty effectively ended when Frank Chance departed after the 1912 season. This marked the beginning of what became baseball's longest championship drought.

Legacy in Chicago

The 1906-1909 Cubs created baseball's first large and dedicated fan base in Chicago. Baseball historian Ray Schmidt documented how the team's success led to the first season ticket waiting lists and the emergence of baseball as a central part of Chicago's cultural identity.

During the 1908 World Series, an estimated 30,000 fans gathered outside the Chicago Daily News building to follow the game on a primitive scoreboard. This marked one of the first major public gatherings to experience baseball collectively, establishing a tradition that would continue with radio and television broadcasts.

The dynasty left such an impression that decades later, older Chicago fans would still talk about Tinker, Evers, and Chance as if they had just played yesterday. This generational storytelling kept the memory of the dynasty alive even as championship hopes faded with each passing decade.

The Dynasty's Place in Baseball History

The 1906-1909 Cubs dynasty stands as a testament to what perfect team chemistry, innovative leadership, and pitching dominance could accomplish. While later dynasties may have captured more championships or featured more household names, few teams have ever dominated their league as thoroughly as these Cubs.

Their legacy includes not just their won-loss record, but also their role in establishing baseball's strategic foundations. The emphasis on "inside baseball"—manufacturing runs through bunts, steals, and hit-and-runs—defined the game until Babe Ruth's power revolution a decade later.

The fact that this dominant Cubs team kicked off what became baseball's most famous championship drought only adds to their mystique. Their story represents both the heights of baseball excellence and the fleeting nature of dynastic success—a fascinating contradiction that makes their four-year run all the more compelling a century later.

Rick Wilton | Diamond Echos

Keeping Baseball's Memories Alive

Footnotes:

- James, Bill. The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. Free Press, 2001.

- Verducci, Tom. "The Case for the 1906-10 Cubs as the Greatest Team of All Time." Sports Illustrated, June 15, 2016.

- Tinker, Joe, Johnny Evers, and Frank Chance Baseball Hall of Fame plaques, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, NY.

- Baseball-Reference.com, Chicago Cubs Team History & Encyclopedia, 1906-1909 seasons.

- Murphy, John. Spink Prize winning article: "Mendoza, Merkle, Mitchell & Morales: Infamous by Association." Baseball Research Journal, Society for American Baseball Research, 2009.

- Retrosheet.org, Box scores and play-by-play accounts, Chicago Cubs 1906-1909.

- Schmidt, Ray. "Taking the Measure of the 1906 Chicago Cubs." The National Pastime, Society for American Baseball Research, 2015.

- Wiles, Tim. Reason to Believe: A Personal Story. Random House, 2009.

- Fleitz, David L. Shoeless: The Life and Times of Joe Jackson. McFarland, 2001.

- Solomon, Burt. The Baseball Timeline. DK Publishing, 2001.

- Vincent, David, Lyle Spatz, and David W. Smith. The Midsummer Classic: The Complete History of Baseball's All-Star Game. University of Nebraska Press, 2001.

- Ritter, Lawrence S. The Glory of Their Times: The Story of the Early Days of Baseball Told by the Men Who Played It. William Morrow & Company, 1966.

- Riess, Steven A. Touching Base: Professional Baseball and American Culture in the Progressive Era. University of Illinois Press, 1999.

- Fangraphs.com, Advanced statistics for Tinker, Evers, and Chance careers and seasonal data.