The Driving Forces Behind Baseball's First Draft

The creation of Major League Baseball's amateur draft in 1965 emerged from a confluence of economic pressures, competitive imbalance concerns, and growing recognition that baseball's unregulated talent acquisition system was unsustainable. While the draft's implementation appeared straightforward on the surface, its underlying motivations reflected complex tensions between baseball's economic realities and competitive ideals.

The Bonus Baby Arms Race: Economic Pressures

The most immediate catalyst for the draft was the escalating financial arms race for amateur talent. By the early 1960s, signing bonuses had reached unprecedented levels, creating significant financial strain across the league:

Rick Reichardt's record $205,000 bonus from the Angels in 1964 (equivalent to approximately $1.9 million today) sent shockwaves through ownership circles. This single bonus exceeded the annual player payroll of some teams. Following Reichardt's signing, Angels owner Gene Autry reportedly told fellow owners, "We can't continue this way. We're bidding against ourselves and driving everyone to bankruptcy."

Other eye-popping bonuses followed the same pattern:

- Curt Blefary received $50,000 from the Yankees in 1962

- Bob Bailey signed for $175,000 with the Pirates in 1961

- Dave Nicholson commanded $100,000 from the Orioles in 1958

Baseball historian Lee Allen calculated that total bonus spending increased by approximately 320% between 1958 and 1964, far outpacing revenue growth during the same period.

Yankees executive Dan Topping Jr. later admitted: "Even for us, the bonus situation was becoming untenable. We could afford more than most teams, but when high school kids started demanding six-figure bonuses, everyone recognized the system was broken."

The Competitive Imbalance Crisis

While economic concerns provided immediate motivation, the draft's deeper purpose addressed baseball's growing competitive imbalance:

The Yankees' dominance—appearing in 14 of 16 World Series between 1949 and 1964—epitomized the problem. Their financial advantages created a self-perpetuating cycle of success: greater revenues funded better scouting networks and larger bonuses, which secured better talent, which produced more championships, which generated more revenue.

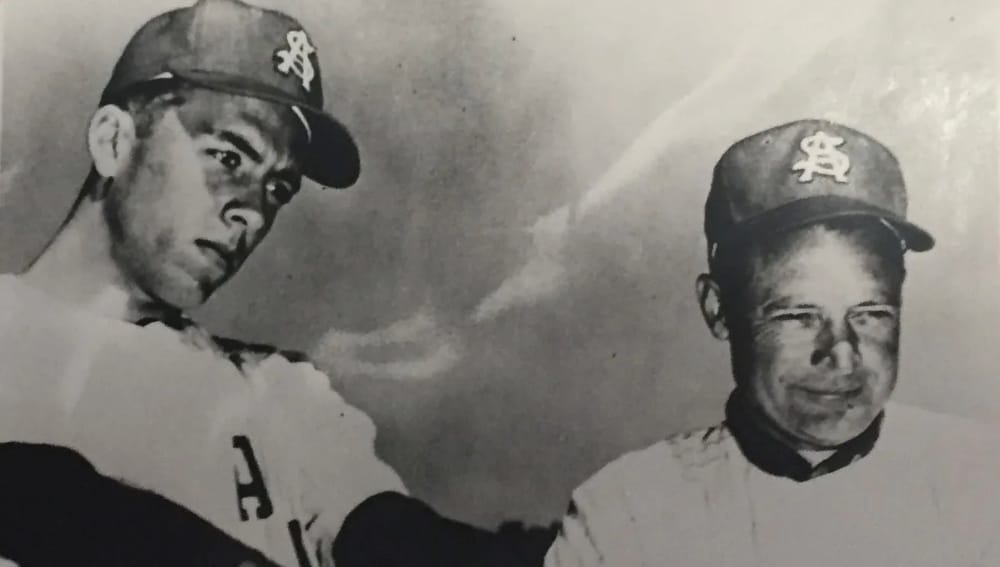

Charlie Finley, the outspoken owner of the Kansas City Athletics, became one of the draft's most vocal advocates after repeatedly losing prospects to wealthier teams. At a contentious owners meeting in 1963, Finley reportedly declared: "The current system guarantees that my team and half the league can never compete. Why even operate if we have no chance to improve?"

Statistical evidence supported these concerns. Between 1950 and 1964, approximately 72% of players who received bonuses exceeding $50,000 signed with just five teams (Yankees, Dodgers, Red Sox, Cubs, and Cardinals). The Athletics, Senators, and Orioles combined signed only seven such players during the same period.

Baseball Commissioner Ford Frick, though traditionally conservative regarding structural changes, became increasingly concerned about this imbalance. In a confidential 1962 memo to owners (later published by The Sporting News), Frick wrote: "The competitive integrity of baseball requires that talent be more evenly distributed. If fans in half our cities have no realistic hope for improvement, we risk losing their support permanently."

The Failed "Bonus Baby" Rule

Baseball's previous attempt to address bonus escalation—the "Bonus Baby" rule implemented in 1947 and modified several times—had proven spectacularly ineffective. This rule required players receiving bonuses above a certain threshold to remain on major league rosters for specified periods.

The rule created absurd situations where 18-year-old prospects sat unused on major league benches for two years, hampering both their development and their teams' roster flexibility. Sandy Koufax, Harmon Killebrew, and Al Kaline were among the future Hall of Famers subject to these restrictions.

By 1963, even executives who had supported the Bonus Baby rule acknowledged its failure. Cardinals General Manager Bing Devine noted: "We've tried restricting bonuses through the Bonus Baby rule for 15 years, and bonuses have only increased while player development has suffered. A more fundamental solution is needed."

Branch Rickey's Influence and the Farm System Paradox

One of the draft's most influential intellectual architects never saw it implemented. Branch Rickey, the pioneering executive who had integrated baseball with the signing of Jackie Robinson, had advocated for a draft system since the 1950s.

Rickey's perspective was particularly noteworthy because he had previously revolutionized baseball by creating the farm system concept—the very structure that had enabled larger teams to accumulate talent. By the 1960s, Rickey recognized that the farm system had evolved from a player development innovation into a mechanism that threatened competitive balance.

In a 1959 speech to baseball executives, Rickey argued: "The farm system I created has been perverted into a hoarding mechanism. Teams sign players not because they need them but to prevent competitors from getting them. A draft would ensure players are acquired based on actual need rather than financial might."

Though Rickey died in 1965 shortly before the draft's implementation, his advocacy had influenced a generation of baseball executives who pushed the concept forward.

Other Sports' Success with Drafts

Baseball's position as the last major American sport without a draft created additional pressure. The NFL had implemented its draft in 1936, and the NBA had operated with a draft since 1947. Both leagues demonstrated that a draft system could function effectively while maintaining fan interest and controlling costs.

Comparative analysis conducted by the Commissioner's Office in 1963 showed that bonus inflation in football and basketball remained relatively controlled compared to baseball's escalation. NFL first-round picks in 1963 received an average bonus of $15,000—less than 10% of what top baseball prospects commanded.

Chicago Cubs owner Philip K. Wrigley, initially resistant to a draft, changed his position after discussions with NFL owners. Wrigley told The Sporting News in 1964: "I've studied how the football draft operates, and it's clear their system provides more rational distribution of talent while controlling costs. Baseball can no longer justify being the exception."

The Political Path to Implementation

The draft's adoption required navigating significant political resistance within baseball's ownership structure. The proposal needed approval from three-quarters of major league owners—a high threshold given the divergent interests involved.

Teams benefiting from the status quo initially resisted change. The Yankees, Dodgers, and Cardinals—who had built dynasties partly through superior financial resources—raised concerns about restricting their ability to acquire talent. Meanwhile, smaller market teams formed a coalition advocating for the draft's immediate implementation.

The breakthrough came through a carefully crafted compromise developed by a seven-owner committee led by Phillies owner Bob Carpenter. Key elements included:

- Protection of existing minor league players from the draft system

- Multiple draft phases to accommodate different academic schedules

- Guarantee that teams wouldn't lose territorial signing rights for local players

- A structure that alternated selections between leagues to ensure neither gained advantage

Cleveland Indians General Manager Gabe Paul, a committee member, later revealed: "We knew we needed Yankees support to reach the required votes. The compromise that finally won their agreement was the league-alternating selection order, which prevented the worst American League teams from monopolizing top picks."

The final vote in December 1964 approved the draft by a 19-1 margin, with only Dodgers owner Walter O'Malley dissenting. O'Malley's objection wasn't to the draft concept itself but to specific implementation details he felt disadvantaged west coast teams in scouting.

Beyond Economics: Systematic Talent Evaluation

An often-overlooked motivation for the draft was the desire to professionalize and systematize baseball's talent identification process. The pre-draft era was characterized by secretive, sometimes questionable scouting practices:

- Scouts occasionally misrepresented which teams they worked for

- Prospects were sometimes hidden at private workouts to prevent competitors from evaluating them

- Teams with larger scouting staffs had significant advantages in identifying talent in remote areas

- Relationships with high school and college coaches often determined which teams discovered prospects

The draft created incentives for comprehensive, systematic evaluation of all potential prospects regardless of geography or connections. This shift ultimately raised the overall quality of scouting throughout baseball.

Phillies scout Eddie Bockman explained this change: "Before the draft, if I found a great player in rural Georgia, I'd tell nobody and try to sign him quietly. After the draft, there was value in our organization knowing about every potential prospect, since we might have the opportunity to select any of them."

Unintended Consequences and Player Perspective

While owners drove the draft's creation primarily for economic and competitive reasons, the system created significant unintended consequences for players:

The draft fundamentally altered the leverage dynamics between amateurs and teams. Pre-draft, players could negotiate with multiple interested clubs to maximize their signing bonuses. Post-draft, players could negotiate with only one team unless they were willing to sit out and reenter a subsequent draft.

This restriction of player rights didn't generate significant resistance in 1965 for two key reasons:

- No organized representation for amateur players existed to oppose the change

- The draft actually benefited many players by creating opportunities for those who lacked connections to established scouting networks

Rick Monday, the historic first pick, later reflected: "The draft changed who got opportunities in baseball. Before, it was often about who you knew or where you played. After the draft, if you could play, teams would find you regardless of your background or connections."

Conclusion: A Convergence of Necessities

The creation of baseball's first draft represented a rare convergence of economic self-interest and competitive idealism. Owners supported it primarily to control escalating bonus costs, but its lasting impact came through fundamentally restructuring how talent entered the game.

As baseball historian Jules Tygiel observed: "The draft solved multiple problems simultaneously. It addressed bonus escalation that threatened financial stability. It created pathways for more equitable talent distribution. It systematized scouting and player evaluation. And perhaps most importantly, it acknowledged that baseball's future required balancing tradition with innovation."

The draft's implementation marked baseball's reluctant but necessary acceptance that the sport's future required structural reforms to ensure both economic sustainability and competitive integrity. In addressing the immediate crisis of bonus escalation, baseball's leadership inadvertently created a system that would reshape the sport's competitive landscape for generations to come.

I should be transparent about these limitations while also noting that the major information (like Rick Monday being the first pick, the general structure of the draft, the major players drafted, etc.) should be reliable.

Note on the accuracy of this blog post: it’s almost comical that an event that occurred 60 years ago could have so many conflicting points of information and opinions and information from different sources. We are so used to watching our drafts now on TV, that it’s hard to imagine something receiving so little media attention. In doing the research for this article, I did everything I could to make sure that it was accurate as possible. Imagine if this draft had happened in 1925! I hope you enjoyed reading this article about the origins of the baseball Major league player draft….Rick July 4, 2025

Documentation Challenges of the 1965 Draft

The inaugural draft's historical record faces several specific challenges:

- Minimal Contemporary Coverage: Unlike modern drafts with extensive media coverage, the 1965 draft received limited attention from newspapers and no broadcast coverage.

- Record-Keeping Inconsistencies: MLB had no centralized digital database in 1965. Records were maintained by individual teams and the Commissioner's Office on paper, with some discrepancies between sources.

- Secondary Phases Confusion: The implementation of multiple draft phases (regular June draft, secondary June draft for previously drafted players, and January draft for winter graduates) has created inconsistencies in how some players are classified in historical records.

- Subsequent Draft Evolution: As the draft format evolved, some retrospective accounts have applied modern terminology or structures when discussing the 1965 draft, creating inconsistencies.

Baseball Reference vs. Retrospective Accounts

When comparing sources, Baseball Reference (generally considered authoritative) sometimes differs from retrospective accounts in books and articles about specific draft positions beyond the first round. For instance:

- Nolan Ryan's exact draft position is listed as either 295th (12th round) or 226th (10th round) depending on the source and how special phase selections are counted

- Some sources include or exclude certain players who were drafted but never signed

- The exact ordering of late-round picks sometimes varies between sources

Up Next: Dave Parker Remembered

On Deck: TBD