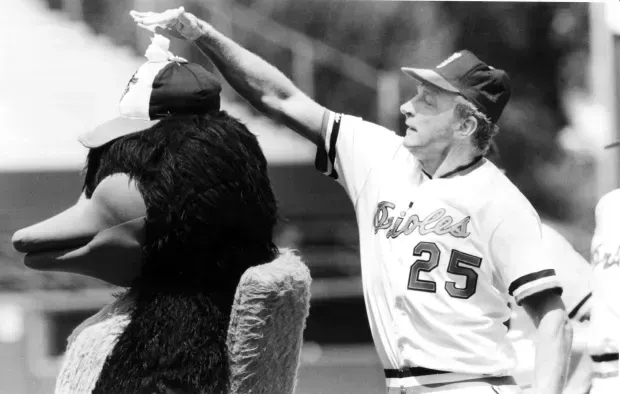

THE PRINCE OF PRANKS: HOW MOE DRABOWSKY ELEVATED BASEBALL'S PRACTICAL JOKES TO AN ART FORM

You never saw a shoe come off so fast in your life.

That's how Moe Drabowsky assessed the effectiveness of the hotfoot he administered to Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn during the Baltimore Orioles' 1970 World Series celebration. Think about that for a moment. A relief pitcher, in the midst of championship jubilation, took time to set the game's highest-ranking official on fire. And he got away with it.

Welcome to the world of Myron Walter "Moe" Drabowsky, baseball's undisputed Prince of Pranks.

Born in Ozanna, Poland, in 1935 and brought to America three years later, Drabowsky pitched 17 seasons in the major leagues. He compiled an 88-105 record with a 3.71 ERA for eight different teams. He earned an All-Star selection in 1967. In Game 1 of the 1966 World Series, he delivered one of the greatest relief performances in Fall Classic history, striking out 11 Dodgers in 6⅔ scoreless innings.

But when Drabowsky passed away in 2006 at age 70, the obituaries led with snakes, bullpen phones, and flaming footwear. And for good reason. Moe Drabowsky didn't just pull pranks. He elevated them to high art.

THE CRAFTSMAN'S APPROACH

What separated Drabowsky from garden-variety clubhouse cutups was his dedication to the craft. His pranks required planning, props, perfect timing, and often a dash of theatrical performance. Consider his masterpiece: the Kansas City bullpen caper of May 27, 1966.

Early in the game at Municipal Stadium, Drabowsky picked up the phone in the Baltimore bullpen and dialed the Kansas City Athletics' bullpen. He'd pitched for the A's previously and knew the phone system intimately. When someone answered, Drabowsky unleashed his best imitation of Kansas City manager Alvin Dark.

"Get Krausse up!" he barked. He ordered reliever Lew Krausse to start warming up immediately. This despite the A's starter cruising along just fine.

A few minutes later, he called again. "Sit him down!"

Then came the third call: "Get him up again!"

By this point, the A's bullpen crew realized they'd been had. They hung up the phone. "You should've seen them scramble, trying to get Lew Krausse warmed up in a hurry," Drabowsky recalled years later. "It was really funny."

The prank demonstrated Drabowsky's signature approach. He understood the phone system. He could impersonate voices. He had patience to make multiple calls and maximize confusion. And he maintained plausible deniability. Who would suspect an opposing team's reliever? This wasn't a whoopee cushion in the manager's chair. This was Ocean's Eleven in flannel.

Drabowsky's bullpen phone exploits became legendary. At Anaheim Stadium, he used the phone to order Chinese food from a restaurant in Hong Kong. When he discovered the Busch Memorial Stadium bullpen phone connected to the main switchboard during his stint with the Cardinals, he made an even bolder call. He phoned a Hollywood movie studio, tracked down actress Sophia Loren at a European hotel, and introduced himself as "Drabo, a great fan." The woman had no idea she was talking to a left-handed relief pitcher calling from a bullpen in St. Louis.

THE SNAKE CHARMER

If phone pranks showcased Drabowsky's logistical genius, his snake work revealed his understanding of psychology and showmanship. Drabowsky didn't just happen upon reptiles. He cultivated relationships with pet shop owners throughout Baltimore who would loan him their inventory for his schemes.

The victims were legion. He placed a garter snake in shortstop Luis Aparicio's pocket. He terrorized outfielder Paul Blair with a four-foot gopher snake draped around his neck as he strolled into the clubhouse. He scattered live snakes in teammates' lockers, shoes, and shaving kits with the frequency of a major league closer racking up saves.

But Drabowsky's pièce de résistance came at a Baltimore sports luncheon. While seated at the head table, he secretly placed a small python inside the bread basket. When Brooks Robinson reached for a roll, he discovered his carbohydrates came with scales. The future Hall of Fame third baseman nearly fell off the dais.

The snake pranks reached their apex during the 1969 World Series. Drabowsky, still maintaining his reputation despite being on the other side, arranged for a seven-foot black snake to be delivered to Memorial Stadium for Game 2. He'd also hired a plane to fly over the stadium during Game 1. The banner read "Beware of Moe" for his former Orioles teammates. Even Yogi Berra wasn't safe from the serpentine assault.

When Drabowsky joined the St. Louis Cardinals in 1971, catcher Ted Simmons discovered a large rubber snake hidden in a towel in his locker. According to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Simmons "let out a scream and broke the Olympic high jump record."

The genius of Drabowsky's snake work wasn't just the shock value. It was his study of human nature. He knew his victims. He understood their vulnerabilities. He timed his strikes for maximum impact. This was psychological warfare disguised as juvenile entertainment.

THE HOTFOOT VIRTUOSO

While other pranksters dabbled in hotfoots, Drabowsky turned it into a science. The hotfoot was a classic gag. You attached lit matches to an unsuspecting teammate's cleats. But Drabowsky didn't just light someone's shoe on fire. He engineered elaborate delivery systems.

For the Kuhn hotfoot, Drabowsky laid a trail of lighter fluid from the trainer's room to the clubhouse. This allowed him to ignite the Commissioner's foot while maintaining his distance and obscuring his identity. The technical sophistication rivaled anything Q provided to James Bond.

Teammate Dick Hall recalled the constant vigilance required in Drabowsky's presence. "You'd be standing there and suddenly feel twinges of heat. It made you jumpy. You can't be tense all the time. After a while we said, 'Hey, no more players.' The poor sportswriters really paid for that."

Indeed, Drabowsky surreptitiously lit the shoes and pants of unsuspecting journalists while they conducted clubhouse interviews. He turned the postgame media session into a potential fire hazard.

THE COMPLETE REPERTOIRE

But Drabowsky's artistry extended beyond his signature work. He inserted three goldfish into opposing teams' water coolers. He placed live mice in teammates' shoes. He lobbed firecrackers under benches and into bullpens. During long airport layovers in the pre-charter flight era, he tied string to a ten-dollar bill. He tossed it on the concourse floor. When strangers reached down to grab it, he yanked it away, sending his teammates into hysterics.

With Luis Aparicio, he swiped a huge papier-mâché Buddha from a Chinese art show in their hotel. They deposited it outside coach Charlie Lau's door. The variety was staggering. Drabowsky never fell into predictable patterns. He never relied too heavily on his greatest hits. Like any true artist, he kept pushing boundaries and exploring new mediums.

THE PRANKSTER PRANKED

Of course, Drabowsky's teammates eventually fought back. When he rejoined the Orioles in 1970, he opened his locker expecting to find his uniform. Instead, he discovered a white groundkeeper's suit, plus yellow raincoat and rain hat for use in tending the field when the weather is inclement. Rakes, shovels, and brooms for infield manicuring completed the ensemble.

Later, while coaching in the Orioles' minor league system, friends on the police force pulled their own prank. They "arrested" him on the field for "cruelty to animals" before revealing it was all a gag. Drabowsky, the master, had become the student.

THE METHOD BEHIND THE MADNESS

Drabowsky wasn't just a chaos agent. He held a college degree from Trinity College and worked as a stockbroker during the off-season. Teammate Denny Walling described him as "really smart." He was an early proponent of using film to study pitching mechanics. He believed deeply in what he called the "five C's" of relief pitching: comfortable grip, confidence, challenging the hitter, control, and concentration.

When asked about his pranks, Drabowsky explained they were "his way of easing the pressure of pitching for a contending team in the major leagues." This wasn't mindless mischief. It was a deliberate strategy for managing the mental demands of professional baseball.

But by 1987, while working as a minor league pitching coach for the Chicago White Sox, Drabowsky lamented what the game had lost. "The players are so serious now," he said. "I think you could still get away with the stuff I did, but no one does."

LEGACY OF LAUGHTER

Moe Drabowsky continued his pranking ways until the end. He brought snakes to fantasy camps and kept the spirit of baseball mischief alive well into the 2000s. When multiple myeloma claimed his life in 2006, he'd fought the disease for six years beyond his initial six-month prognosis. He displayed the same stubborn creativity that defined his playing career.

His teammate Boog Powell perhaps said it best. "Obviously, Moe's parents never let him have toys when he was little, so he had a lot of catching up to do. He sat around and dreamed up things. He was basically insane. That's all there was to it."

But Drabowsky wasn't insane. He was an artist working in an unconventional medium. He was a craftsman who understood that baseball's 162-game grind demanded relief of a different kind than what he provided from the bullpen. In an era when athletes are branded commodities afraid to show personality, when social media turns every misstep into a scandal, we could use a few more practitioners of Drabowsky's peculiar art form.

After all, any game that can't make room for a relief pitcher calling Hong Kong from the bullpen phone is taking itself far too seriously. The same goes for giving the Commissioner a hotfoot at a World Series celebration.