The St. Louis Browns: Baseball's Forgotten Franchise

Ever wonder what happened to that other St. Louis baseball team? For over 50 years, the Browns fought for the hearts of St. Louis fans before losing the city to the Cardinals and eventually becoming today's Baltimore Orioles. Their story has it all - weird promotions.

The St. Louis Browns: Arrival in the Mound City

St. Louis was booming when the Browns rolled into town in 1902. The city buzzed with excitement for the upcoming 1904 World's Fair, which would bring nearly 20 million visitors and put St. Louis on the map.

The Browns weren't brand new to baseball--they'd spent their first season as the Milwaukee Brewers in 1901, one of the American League's original eight teams. The league's ambitious president, Ban Johnson, figured he could make more money in St. Louis, so he helped broker a deal to pack up the team and head south.

Taking the "Browns" Name

The team grabbed the "Browns" name from St. Louis baseball history. The original St. Louis Browns had played in the National League back in the 1880s before eventually becoming the Cardinals. By picking up this old name, the American League newcomers hoped to connect with local baseball fans while building something fresh.

The St. Louis Republic newspaper welcomed them with open arms: "The American League Browns will bring a fresh spirit of competition to our baseball scene. With the National League Cardinals struggling, many fans are eager for a winning alternative."

Settling into Sportsman's Park

The Browns set up shop at Sportsman's Park, on the corner of Grand Boulevard and Dodier Street in north St. Louis. They started as renters, but in 1920 they bought the place outright, creating the odd situation where they owned the stadium and rented it to their National League rivals. "The Cardinals, who began sharing Sportsman’s Park in 1920, became tenants of their eventual rivals."

The original wooden ballpark held about 8,000 fans. Nothing fancy, but typical for early 1900s baseball--fans sat close to the action with few frills.

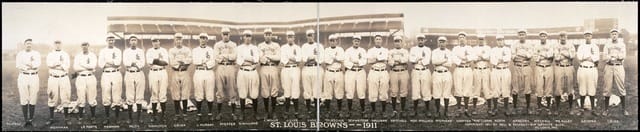

The First Browns Roster

That first St. Louis Browns team had a few standout players among the mostly forgotten names:

- Jesse Burkett (OF, STL) hit .306 and led the offense

- Jack Powell (RHP, STL) won 22 games as the staff ace

- Bobby Wallace (SS, STL) began what would become a Hall of Fame career with the Browns, sticking with the team for 15 seasons

Manager Jimmy McAleer guided this group to a solid 78-58 record and second place finish in 1902. Pretty good for a team in a new city!

Birth in the Mound City

After just one year in Milwaukee, the Browns found St. Louis at the perfect time. The city was growing fast with the World's Fair approaching, and the Cardinals weren't winning many games. The Browns moved into Sportsman's Park, which they'd eventually buy and then rent back to the Cardinals.

Early Years: Hope and Heartbreak

The Browns had some decent years early on. George Sisler (1B, STL) became their first real star in the 1910s, hitting an eye-popping .407 in 1920 and .420 in 1922. His 257 hits in 1920 stood as the major league record for 84 years until Ichiro broke it.

The team came tantalizingly close to a pennant twice, finishing second under manager Fielder Jones in 1916 and again under manager Lee Fohl in 1922. But second place was as good as it got--the Browns always found new ways to fall short.

The "Only in St. Louis" Years

By the 1930s, the Browns were stuck in the basement while watching the Cardinals become a National League powerhouse. With few wins to celebrate, they became known for wacky promotions instead of baseball success.

Owner Bill Veeck once sent 3-foot-7-inch Eddie Gaedel (PH, STL) to bat in 1951, wearing uniform number "1/8." Gaedel walked on four pitches in his only big league appearance before baseball commissioner Ford Frick banned the stunt.

Wartime Wonder: 1944 American League Champions

The Browns' only real glory came during World War II when many star players were in military service. In 1944, they shocked baseball by winning their only American League pennant with 89 victories.

This led to the famous "Streetcar Series" against the Cardinals, their Sportsman's Park roommates. The Cardinals won in six games, crushing the Browns' only shot at a championship.

The Streetcar Series: When St. Louis Owned October

The 1944 World Series between the Browns and Cardinals stands as one of baseball's most unusual championship matchups. Fans called it the "Streetcar Series" because they could hop a trolley to Sportsman's Park to watch both teams. It's still the only all-St. Louis World Series ever played.

A City Divided

Fall 1944 turned St. Louis into baseball's capital. With gas rationed during World War II, the "Streetcar Series" got its name honestly--fans really did ride streetcars to games since driving wasn't an option for most.

The city split down the middle. The Cardinals had built a strong fan base through their success in the 1920s and 1930s, but the Browns' surprise pennant created a wave of underdog support. Even some longtime Cardinals fans pulled for the scrappy American Leaguers.

Local shops displayed both team pennants. Neighborhood bars became battlegrounds for baseball arguments. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch and Star-Times filled pages with player profiles and game breakdowns.

Same Park, Different Home Teams

What made this Series truly weird was that both teams called Sportsman's Park home. The Browns owned the stadium and rented it to the Cardinals. For the Series, they just took turns being the home team in the same ballpark.

The grounds crew had to switch the dugouts between games. When the Browns were "home," they sat in the first-base dugout. For Cardinals home games, the teams swapped sides. The scoreboard operator had to keep track of which team was "home" for each game.

Wartime Baseball Takes Center Stage

The 1944 Series happened while the world was at war. Many star players were serving in the military, which partly explains how the usually mediocre Browns managed to win the pennant.

Both teams featured players classified 4-F (unfit for military service) or those with deferments. Some had physical issues that kept them out of the service but not off the baseball field. Others were older players who stepped up when younger stars went to war.

The Browns' roster included guys like Sig Jakucki (RHP, STL), who hadn't pitched in the majors since 1936 before making his comeback, and Mike Kreevich (OF, STL), a 34-year-old outfielder having one of his best seasons.

The Series Itself

The Cardinals came in as heavy favorites despite the Browns winning more games between the teams during the regular season. Game 1 went to the Browns 2-1 behind Denny Galehouse's (RHP, STL) strong pitching, briefly raising hopes for an upset.

The Cardinals bounced back to win Game 2, but the Browns took a 2-1 series lead by winning Game 3. The pivotal Game 4 went to the Cardinals, tying the series. In Game 5, Cardinals ace Morton Cooper threw a brilliant shutout to win 2-0.

In Game 6, with a chance to force Game 7, the Browns took a 1-0 lead into the fourth inning. But the Cardinals scored three runs and held on for a 3-1 win, grabbing their second straight World Series title and fifth overall.

Vern Stephens (SS, STL) starred for those Browns teams, hitting 24 home runs in their pennant year. Jack Kramer (RHP, STL) won 17 games with a solid 2.49 ERA in 1944.

The One-Armed Wonder: Pete Gray

Pete Gray (OF, STL) played the 1945 season with one arm, inspiring fans nationwide while hitting .218 in 77 games.

Ned Garver's Remarkable 1951

Ned Garver (RHP, STL) somehow won 20 games for a team that lost 102 games in 1951, accounting for nearly a third of the team's 52 victories.

Goodbye St. Louis, Hello Baltimore

After the 1953 season, the Browns packed up and headed east. On September 27, 1953, they played their final game as the St. Louis Browns, losing 2-1 to the Chicago White Sox in front of just 3,174 fans.

The franchise became the Baltimore Orioles in 1954, eventually building a winning tradition with multiple World Series titles. Meanwhile, St. Louis became Cardinals-only territory, with memories of the Browns fading each year.

The Browns left St. Louis with a lousy overall record: 3,414 wins against 4,465 losses, for a .433 winning percentage. Still, they remain an important piece of baseball history--the team that couldn't quite make it in a city that only had room for one franchise.

The Numbers Tell the Story

The stats show how World War II affected baseball quality:

- The Browns won the 1944 AL pennant with just 89 victories -- one of the lowest win totals for a pennant winner in the 154-game schedule era.

- League-wide batting averages fell to .260 in the AL (down from .283 in 1936).

- Home runs dropped sharply across baseball.

- Strikeout rates decreased as pitching quality declined.

Browns manager Luke Sewell admitted in a Post-Dispatch interview: "We wouldn't have had a chance in a normal year. But these aren't normal times, and we took advantage."

Eddie Gaedel: The 3-foot-7 Pinch Hitter

When Veeck sent tiny Eddie Gaedel to bat against Detroit on August 19, 1951, the crowd of 18,369 (a rare big turnout at Sportsman's Park) didn't know what to make of it at first.

"There was this strange silence," recalled Bob Broeg of the Post-Dispatch. "Then laughter rippled through the stands. By the time he reached the batter's box, people were standing and cheering."

Fans' shock quickly turned to delight. When Gaedel walked on four pitches and trotted to first base, the crowd gave him a standing ovation. One fan yelled, "Throw him a low one!" which got everybody laughing.

While fans loved it, baseball big shots were furious. American League President Will Harridge called it "making a mockery of the game" and immediately voided Gaedel's contract. St. Louis sportswriter J. Roy Stockton called it "a belittling burlesque."

But fans disagreed. The Browns' switchboard lit up with calls praising the stunt, and attendance jumped for several games afterward. Letters to the Post-Dispatch sports section ran about 8-to-1 in favor of Veeck's creativity.

Pete Gray: The One-Armed Outfielder

Pete Gray (OF, STL) played the 1945 season with one arm, becoming an inspiration to wounded war veterans and disabled Americans everywhere. Despite his physical limitation, Gray hit .218 in 77 games--a remarkable achievement that went beyond baseball.

Gray's presence on the Browns roster highlighted both wartime baseball's unique character and the Browns' willingness to think outside the box. His story got national media attention that the Browns rarely received otherwise.

Though Gray's major league career lasted just one season, his legacy lives on through books, documentaries, and his inspiration to generations of disabled athletes. His Browns uniform and glove (which he would shift to his playing hand after catching a ball) remain on display at the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Grandstand Managers Day

In 1951, Veeck handed out thousands of "YES" and "NO" cards to fans, letting them vote on game decisions during a matchup against the Athletics.

"It was like being at a political convention," said longtime Browns fan Harold Mueller in a 1983 interview. "Everyone waving cards, arguing with neighbors about whether to bunt or hit away. Most fun I ever had at a ballgame."

The Browns won 5-3, and fans celebrated "their" victory. After the game, manager Zack Taylor joked, "Maybe we should let them manage more often."

Traditional baseball men weren't amused. Yankees manager Casey Stengel said, "If that's what it takes to get people to watch the Browns, maybe they shouldn't have a team." But attendance for the promotion hit 4,500--nearly double their season average.

Grandma Promotion Day

When Veeck announced "Grandmothers Day" in 1952, inviting grandmothers to attend free and join pre-game activities, many expected another circus. Instead, it became one of his most heartwarming promotions.

More than 5,000 grandmothers showed up, with 97-year-old Ida Johnson the oldest. Before the game, the grandmothers paraded around the field. Several told reporters it was their first live baseball game.

"I've seen grown men cry watching those ladies circle the field," said Browns usher Frank Marston years later. "It wasn't about gimmicks--it connected generations."

Even hard-boiled sportswriters praised this promotion. Sid Keener wrote, "For once, Veeck found the perfect balance between promotion and respect for the game."

The George Sisler Era: Baseball's Forgotten Superstar

George Sisler (1B, STL) was probably the greatest player ever to wear a Browns uniform. From 1915-1927, he amazed St. Louis fans with incredible hitting and fielding. His 1920 season (.407 average, 257 hits) and 1922 campaign (.420 average) rank among baseball's all-time best offensive performances.

What makes Sisler's story sad is how his career path changed after a bad sinus infection damaged his vision before the 1923 season. Though he played several more seasons, he never got back to his superstar level. Despite this setback, Sisler made the Hall of Fame in 1939.

The Browns' failure to build a winner around a player of Sisler's talent says a lot about the franchise's problems. While with the Browns, Sisler never played in a World Series despite his individual brilliance.

Urban Shocker and the Great Pitching Staff That Never Was

Urban Shocker (RHP, STL) was one of baseball's most underrated pitching talents. From 1918-1924, he dominated for the Browns, winning 20+ games four straight seasons with pinpoint control and a nasty spitball.

The Browns briefly built an impressive rotation around Shocker that included Dave Danforth (LHP, STL) and Dixie Davis (RHP, STL). If the team had kept their finances in order and held this core together, they might have contended throughout the 1920s.

Instead, they traded Shocker to the Yankees in 1925, where he helped New York win pennants while the Browns sank in the standings. This pattern--developing talent only to see it succeed elsewhere--became a Browns trademark.

The Baltimore Transition: From Browns to Orioles

The Browns' transformation into the Baltimore Orioles represents one of baseball's most dramatic franchise turnarounds. The move after the 1953 season initially looked like just relocating failure--the team finished seventh in their first Baltimore season.

However, under new ownership and management, the franchise slowly built a player development system that became baseball's gold standard. By the late 1960s, the former Browns had become a model organization, winning multiple World Series between 1966-1983.

The stark contrast between the St. Louis failure and Baltimore success makes you wonder whether environment, ownership, or just plain baseball luck determines a franchise's fate.

Could the Browns Have Survived Elsewhere? The Road Not Taken

The Browns' failure in St. Louis raises an interesting what-if question: Could the franchise have thrived if it had moved to a different city earlier? Several good options existed after World War II, each offering the Browns a fresh start without the Cardinals' shadow.

Milwaukee: The Missed Opportunity

Bill Veeck's attempt to move the Browns to Milwaukee in 1952 represents the franchise's biggest "what if" scenario.

Milwaukee offered several advantages:

- County Stadium was being built specifically for major league baseball

- The city had a strong minor league following with the Brewers averaging 300,000+ fans yearly

- Wisconsin had no major league team but loved baseball

- Local breweries could provide corporate sponsorship

When American League owners blocked Veeck's Milwaukee proposal in 1952, they basically sentenced the Browns to another year of St. Louis struggles. Just months later, they approved the Boston Braves' move to Milwaukee, where that team drew over 1.8 million fans in 1953--six times what the Browns attracted in St. Louis.

Fred Saigh, then Cardinals owner, later admitted: "Milwaukee would have embraced the Browns. The American League made a terrible mistake blocking that move."

Los Angeles: The Western Frontier

Los Angeles was another solid option that Veeck explored. Since St. Louis was the westernmost major league city until 1958, moving to California offered pioneering advantages:

- The Los Angeles market had over 4 million people by 1950

- The minor league Los Angeles Angels drew big crowds at Wrigley Field (LA)

- No major league competition existed west of St. Louis

- Television potential far exceeded anything in the Midwest

Sports historian David Quentin Voigt wrote in a 1976 SABR article: "Had the Browns moved to Los Angeles in 1952 or 1953, they likely would have established West Coast baseball years before the Dodgers and Giants. The first team in would have captured incredible market advantages."

The Browns could have beaten the Dodgers to LA by 5+ years, potentially becoming Southern California's established team.

Kansas City: The Regional Shift

Kansas City, which eventually got the Athletics in 1955, presented another logical landing spot:

- The city had MLB-caliber Municipal Stadium, home to the minor league Blues

- Geographic proximity to St. Louis would have kept some existing fan relationships

- The market had shown baseball interest through strong minor league support

- Regional rivalries with Detroit, Chicago, and Cleveland could have developed

Baseball economist Andrew Zimbalist noted in a 1990s retrospective: "Kansas City ultimately supported major league baseball adequately. Had the Browns arrived first, with a chance to establish loyalty before competing franchises, they might have found stability there."

Houston: The Southern Opportunity

Though less talked about, Houston emerged as a potential destination in early 1950s discussions:

- Texas had no major league team but strong baseball tradition

- Oil money could have provided financial backing

- The city's population was growing rapidly

- The climate allowed for year-round baseball operations

Browns general manager Bill DeWitt actually commissioned a market study of Houston in 1952 that concluded: "Houston represents the most promising untapped baseball market in America. Within five years, it will be capable of supporting major league baseball."

Conclusion: Viability Beyond St. Louis

The evidence strongly suggests the Browns could have succeeded in multiple alternative locations if they had moved earlier with adequate resources and leadership. Their failure in St. Louis reflected specific circumstances--primarily competition with the Cardinals--rather than inherent franchise defects.

The Orioles' eventual success in Baltimore confirms that the organization could build a winner given the right environment. Milwaukee's enthusiastic embrace of the Braves after rejecting the Browns shows that timing and league politics, rather than market potential, often determined franchise outcomes in the 1950s.

Perhaps the most telling evidence comes from Bill Veeck himself, who wrote in his memoir "Veeck as in Wreck": "The Browns didn't fail because they were the Browns. They failed because two teams couldn't survive in a city that barely had enough baseball passion for one. Anywhere else, with any kind of head start, they could have written a completely different story."