From the Association to American League: The Early Washington Nationals

The history of baseball in Washington, D.C. goes back much further than most fans realize. Long before the current Washington Nationals took the field in 2005, our nation's capital had a rich--and often frustrating--baseball tradition. The story begins not with the more familiar Washington Senators, but with earlier teams that laid the groundwork for D.C. baseball.

THE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION YEARS: WASHINGTON'S FIRST MAJOR LEAGUE TEAM

Birth of the Original Nationals (1884)

Washington's first real taste of major league baseball came when the Washington Nationals joined the American Association. Back then, the American Association was considered a major league, though it operated as a rival to the more established National League.

The team played at Athletic Park, a simple wooden structure at 7th Street and Florida Avenue in 1884. Tickets cost 25 cents for the cheap seats, and fans could watch the game while enjoying a beer—something the more— straightlaced National League didn't allow.

Team owner Robert C. Hewitt hoped Washington's political crowd would embrace baseball, but the 1884 Nationals struggled badly. They finished with a miserable 12-51 record (.190 winning percentage), dead last in the 12-team league. After one terrible season, the Nationals folded. Washington wouldn't see another American Association team.

THE NATIONAL LEAGUE COMES TO WASHINGTON (1886-1889)

A Brief National League Stint

Two years after the American Association disaster, Washington tried again with a National League team, also called the Nationals. This version lasted a bit longer—four seasons from 1886 through 1889.

The team played at Swampoodle Grounds, located near present-day Union Station. The field got its nickname from the swampy conditions that plagued the area after heavy rains.

Washington's National League team provided few highlights for local fans. Their “best” season came in 1886 when they finished sixth (out of 8) with a 28-92 record. By 1889, attendance had dropped so low that the franchise folded after a 41-83 campaign.

During this brief run, the team featured catcher Connie Mack (C/MGR, WSH), who later became one of baseball's greatest managers with the Philadelphia Athletics. Mack hit just .201 in 1888 but showed the baseball intelligence that would later make him famous.

THE AMERICAN LEAGUE ARRIVES: BIRTH OF THE SENATORS

Ban Johnson's New League (1901)

After nearly a decade without major league baseball, Washington got another chance when Ban Johnson expanded his Western League and renamed it the American League in 1901, declaring it a major league to compete with the National League.

Johnson placed a franchise in Washington, bringing the national pastime back to the nation's capital. This team, originally called the Washington Nationals in official league documents, quickly became known as the Senators in newspaper accounts and among fans.

The new Washington club played at American League Park (later renamed National Park, then Griffith Stadium). The original wooden structure seated about 10,000 fans.

The Early Struggles (1901-1904)

The new Washington team looked a lot like the old Washington teams—they lost. A lot. They finished last in 1901 with a 61-72 record and sixth in 1902 at 61-75. A young pitcher named Walter Johnson (RHP, WSH) wouldn't arrive until 1907, so these early teams lacked star power.

Manager Tom Loftus couldn't build a winner despite future Hall of Famer Ed Delahanty (OF, WSH), who hit .376 in 1902. Tragically, Delahanty died during the 1903 season when he fell from a bridge into Niagara Falls under mysterious circumstances.

THE RISE OF WALTER JOHNSON

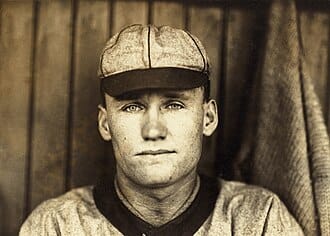

The Big Train Arrives (1907)

The fortunes of Washington baseball changed forever on August 2, 1907, when a shy farm boy from Kansas named Walter Johnson (RHP, WSH) made his debut. Johnson lost that first game 3-2 to the Detroit Tigers, but the 19-year-old's blazing fastball caught everyone's attention.

"The first time I faced him," Detroit star Ty Cobb later recalled, "I watched him take that easy windup, and then something went past me that made me flinch. I hardly saw the pitch, but I heard it. Every one of us knew we'd met the most powerful arm ever turned loose in a ballpark."

Johnson's nickname "The Big Train" came from his fastball that sounded like a locomotive as it popped into the catcher's mitt. Despite Johnson's talent, Washington remained a second-division team through his early years.

Johnson's Amazing 1913 Season

By 1913, Johnson had developed into baseball's most dominant pitcher. That season, he put together one of the greatest pitching performances ever: 36 wins, 7 losses, 1.14 ERA, 243 strikeouts, and 11 shutouts. His ERA+ of 259 remains one of the highest single-season marks in history.

The advanced metrics show just how special Johnson was. His 15.2 WAR (Baseball-Reference version) in 1913 stands as the highest single-season WAR for any pitcher in American League history.

Still, the Senators finished second that year, 6.5 games behind the Philadelphia Athletics. Despite having baseball's best pitcher, Washington couldn't build a championship team around him.

THE CLARK GRIFFITH ERA BEGINS

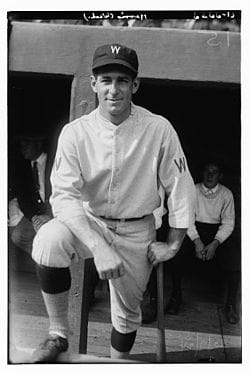

The Old Fox Takes Over (1912)

In 1912, a significant change came to Washington baseball when Clark Griffith, a former star pitcher turned manager, bought a 10 percent stake in the team and became manager. Griffith, known as "The Old Fox" for his baseball smarts, would shape Washington baseball for the next four decades.

Under Griffith's leadership, the team improved quickly. They jumped to second place in 1912 and repeated that finish in 1913. After years of failure, Washington fans finally had a competitive team to cheer for.

In 1919, Griffith increased his ownership stake and became team president. He renamed the ballpark after himself—Griffith Stadium—and began building what would eventually become a championship team.

Building Around Johnson

Griffith knew that Johnson was a once-in-a-lifetime talent, but he also knew that even the great Johnson couldn't win alone. Through the late 1910s and early 1920s, Griffith slowly built a team that could compete.

He signed a slick-fielding shortstop named Roger Peckinpaugh (SS, WSH), added slugger Goose Goslin (OF, WSH), and developed second baseman Bucky Harris (2B/MGR, WSH) into a team leader.

By 1923, Johnson was 35 years old, but still effective. Griffith knew his window for building a winner around Johnson was closing. He needed just a few more pieces.

THE 1924 WORLD CHAMPIONS: WASHINGTON'S FINEST HOUR

Bucky Harris Takes the Reins

In 1924, Clark Griffith made a bold move. He named 27-year-old second baseman Bucky Harris as player-manager, making him the youngest manager in the league. Many criticized the decision, but Griffith saw leadership qualities in the young infielder.

"I know he's young," Griffith told the Washington Post, "but he knows this team and he knows how to win."

Harris quickly proved Griffith right. He managed the team skillfully while continuing to play second base at a high level, hitting .268 with a .349 OBP.

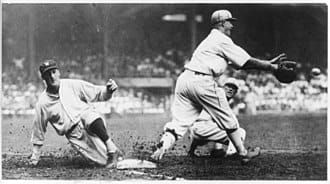

The Senators' Magical Season

The 1924 Washington Senators featured a mix of aging stars and young talents. Walter Johnson, now 36, remained the staff ace, going 23-7 with a 2.72 ERA. He was joined by George Mogridge (LHP, WSH) and Tom Zachary (LHP, WSH) in a solid rotation.

The offense was led by Goose Goslin (OF, WSH), who hit .344 with 12 home runs and a .421 OBP. Sam Rice (OF, WSH) added speed and a .334 batting average, while Joe Judge (1B, WSH) contributed a .324 average.

After years of disappointment, the Senators finally reached the top of the American League, finishing 92-62 to edge out the Yankees by two games. Washington was going to the World Series!

The 1924 World Series: High Drama in D.C.

The Senators faced John McGraw's New York Giants in the World Series. The Giants had won the previous two World Series and entered as heavy favorites.

The Series opened at Griffith Stadium with Walter Johnson on the mound. Surprisingly, the Giants roughed up the Big Train, winning 4-3 in 12 innings. Washington bounced back to win Game 2 behind rookie pitcher Tom Zachary (LHP, WSH).

After splitting the next two games, Johnson returned for Game 5 but lost again, putting Washington on the brink of elimination, down 3-2 in the Series.

The Senators weren't done, though. They won Game 6 in New York, setting up a decisive Game 7 at Griffith Stadium.

Game 7: Washington's Greatest Baseball Moment

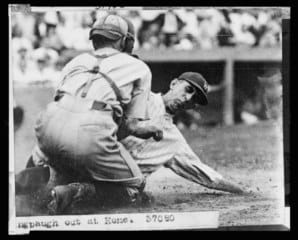

Game 7 turned into one of the most dramatic in World Series history. With the score tied 3-3 in the eighth inning, Bucky Harris called on Walter Johnson to pitch in relief. The Big Train, desperate for his first World Series win after two losses in the Series, threw four shutout innings.

In the bottom of the 12th, with Johnson still pitching, Senators catcher Muddy Ruel (C, WSH) hit a pop-up that Giants catcher Hank Gowdy dropped when he tripped over his own mask. Given new life, Ruel doubled. Then Earl McNeely (OF, WSH) hit a ground ball that took a bad hop over the third baseman's head, scoring Ruel with the winning run.

Washington had won its first World Series! The city went wild with celebration. President Calvin Coolidge welcomed the team to the White House the next day, and Walter Johnson finally had his championship after 18 seasons.

"I'd have given every honor I ever received to win this one," Johnson told reporters after the game, tears in his eyes.

THE 1925 AMERICAN LEAGUE CHAMPIONS

Back for More

Incredibly, the Senators didn't suffer a championship hangover. They came back even stronger in 1925, winning 96 games and returning to the World Series.

The '25 team featured many of the same stars: Goslin hit .334 with 18 home runs and 113 RBIs, while Rice batted .350 and Johnson won 20 games despite being 37 years old.

The Senators' shortstop, Roger Peckinpaugh (SS, WSH), won the award despite a modest slash line of .292/.367/.414 with four home runs and 65 RBI. His 4.4 WAR was third among the team's position players, trailing Sam Rice (4.5) and Goose Goslin (6.5). His selection was therefore surprising, especially over sluggers like Al Simmons (.387 BA, 34 HR, 129 RBI) and Harry Heilmann (.393 BA, 13 HR, 134 RBI).

The explanation lies in the award's unique philosophy and rules at the time. The American League's "League Award," as it was known, was intended to honor the player who provided the "greatest all-around service to his club," not just the best statistical performer. Furthermore, quirky voting rules made many top candidates ineligible; player-managers like Ty Cobb and previous winners like Babe Ruth and Eddie Collins could not be selected. This cleared the path for Peckinpaugh, the respected leader of a pennant-winning team, to claim the honor.

World Series Heartbreak

In the 1925 World Series, Washington faced the Pittsburgh Pirates. The Senators took a commanding 3-1 lead in the Series and seemed headed for back-to-back championships.

Then disaster struck. The Pirates won Game 5 in Pittsburgh, then Game 6 in Washington. In Game 7, played in a torrential downpour that should have caused a postponement, the Senators blew a 4-0 lead. Walter Johnson, pitching on two days' rest at age 37, couldn't hold the lead. Pittsburgh won 9-7, completing an improbable comeback.

The Senators had come within one game of a second straight title. They didn't know it at the time, but they'd never get that close again.

THE FINAL YEARS IN WASHINGTON

After their back-to-back pennants in the 1920s, the Senators remained competitive but couldn't get over the top, and the team's icon, Walter Johnson, retired after the 1927 season. However, the franchise had one final moment of glory in them.

Washington's Last Hurrah: The 1933 PennantIn 1933, led by 26-year-old player-manager Joe Cronin, the Senators surprised the baseball world by winning 99 games and capturing the American League pennant. The offense was powered by Cronin, Heinie Manush (.336 BA), and a returning Goose Goslin, while pitcher Alvin "General" Crowder anchored the staff with 24 wins.

In the 1933 World Series, Washington faced the New York Giants, the same club they had vanquished in 1924. This time, however, the result was different. The Giants, led by the brilliant pitching of Carl Hubbell, took the Series in five games. The championship magic of 1924 could not be recaptured.

The 1933 pennant would be the franchise's last. While the team followed up with a strong 99-53 record in 1934, it was only good for second place behind the 101-win Detroit Tigers. It was their last serious championship challenge in D.C., as financial pressures and mediocrity would soon define the club's final decades in the capital.

Financial Troubles and Declining AttendanceThroughout the late 1930s and 1940s, the Senators settled into mediocrity. They had stars like Roy Sievers (1B/OF, WSH) and Cuban star pitcher Connie Marrero (RHP, WSH)—but never came close to winning another pennant.

Attendance dropped as the team struggled. The old saying "Washington: First in war, first in peace, and last in the American League" became the team's unwanted slogan.

By the early 1950s, even with decent talents like Mickey Vernon (1B, WSH) and Eddie Yost (3B, WSH), the franchise was losing money. Television had begun changing baseball economics, and Washington—the 9th largest market in the 16-team major leagues—couldn't keep up financially.

The Move to MinnesotaOn October 26, 1960, after 60 years in Washington, the Senators played their final game in D.C., losing to Baltimore 2-1. Owner Calvin Griffith, who had taken over after Clark Griffith's death, announced the team would move to Minneapolis-St. Paul for the 1961 season.

"I didn't want to move the team," Griffith claimed, "but we couldn't make it financially in Washington."

The move shocked and angered Washington fans, who had supported the team through six decades of mostly losing baseball. As a consolation, Major League Baseball awarded Washington an expansion team, also called the Senators, who began play in 1961. They too would eventually leave, moving to Texas in 1972.

The original Senators, renamed the Minnesota Twins, found quick success in their new home, reaching the World Series in 1965. Washington would wait 44 years—until 2005—for major league baseball to return.

THE LEGACY OF WASHINGTON'S ORIGINAL TEAM

Hall of Famers and Franchise Icons

Despite their mostly losing ways, the original Washington franchise produced several Hall of Famers:

• Walter Johnson (RHP, WSH) - Perhaps the greatest pitcher ever, with 417 wins and a 2.17 ERA

• Goose Goslin (OF, WSH) - Hit .316 over his career with 248 home runs

• Sam Rice (OF, WSH) - Collected 2,987 hits and a .322 career average

• Joe Cronin (SS/MGR, WSH) - Batted .301 lifetime as a shortstop and successful manager

• Bucky Harris (2B/MGR, WSH) - The "Boy Wonder" manager who led Washington to its only World Series title

What Might Have Been

Washington's baseball history is filled with "what ifs." What if Walter Johnson had played for a consistently good team throughout his career? What if the Senators had held onto that 3-1 lead in the 1925 World Series? What if they had found a way to stay financially viable in Washington?

We'll never know those answers, but we do know that Washington's baseball roots run deep. The success of today's Nationals—who finally brought a World Series back to D.C. in 2019—helps heal some of the old wounds left by the original team's departure.

KEY PLAYERS IN FRANCHISE HISTORY

Walter Johnson: The Big Train

No discussion of Washington baseball can begin anywhere but with Walter Johnson. His 417 wins, 3,509 strikeouts, 110 shutouts, and 2.17 ERA established him as perhaps the greatest pitcher in baseball history.

Johnson's 152.3 career WAR ranks second all-time among all players, trailing only Babe Ruth. He led the American League in strikeouts 12 times and ERA five times.

Beyond his stats, Johnson was known for his sportsmanship and humble personality. Despite his blazing fastball, he refused to throw at hitters' heads, saying he couldn't bear the thought of seriously injuring someone.

When he died in 1946, President Harry Truman called him "one of the greatest Americans."

Goose Goslin: Washington's Slugger

While Johnson dominated on the mound, Leon "Goose" Goslin (OF, WSH) provided the offensive firepower for the great Washington teams of the 1920s.

Goslin hit .328 with a .429 OBP and 24 home runs for the 1924 championship team. His lifetime batting average of .316 and OPS+ of 128 show just how valuable he was with the bat.

Though not known for his defense (his nickname "Goose" came from his awkward fielding style), Goslin's hitting made him a fan favorite in Washington. He ranks as one of the most productive outfielders of the 1920s.

Sam Rice: The Hit Collector

Sam Rice (OF, WSH) spent almost his entire 20-year career with Washington, collecting 2,987 hits—just 13 shy of the magical 3,000 mark. His .322 career average and speed on the bases made him the perfect complement to Goslin's power.

Rice is best remembered for a controversial catch in the 1925 World Series, when he tumbled into the stands to grab a fly ball. Whether he actually held onto the ball became one of baseball's great mysteries, as Rice refused to say definitively until after his death, when a sealed letter revealed he had indeed made the catch.

Joe Cronin: Star Shortstop and Boy Manager

Joe Cronin (SS/MGR, WSH) joined the Senators in 1928 and quickly developed into a star. By 1930, he was hitting .346 with 126 RBIs. His OPS+ of 130 as a shortstop made him one of the most valuable players in the league.

In 1933, at just 26, Cronin was named player-manager, following Bucky Harris's example of a decade earlier. He led Washington to 99 wins and a third-place finish in his first season, then to the AL pennant in 1933 with a 99-53 record.

Cronin was later traded to Boston in a controversial deal that many saw as the beginning of Washington's decline.

WHAT WENT WRONG? WHY WASHINGTON LOST ITS TEAM

Economic Forces

The departure of the original Senators in 1960 resulted from several factors. Most importantly, the economics of baseball had changed dramatically after World War II.

Television had emerged as a major revenue source, but Washington's TV market, while not small, couldn't compete with New York, Chicago, or Los Angeles. The Senators' radio and TV contracts paid far less than those of teams in larger markets.

Poor Performance and Falling Attendance

After their 1933 pennant, the Senators rarely contended. They finished above .500 only three times between 1934 and 1960. This consistent losing drove fans away.

Attendance, which had topped 1 million in 1946, fell to just 743,404 by 1960. With 81 home games, that meant fewer than 10,000 fans per game in a stadium that held over 30,000.

Outdated Facility

Griffith Stadium, charming as it was, had become outdated by the 1950s. Built in 1911, it lacked the modern amenities fans expected. Parking was limited, concessions were basic, and the neighborhood around the stadium had declined.

Other teams were building new, suburban stadiums with ample parking and family-friendly features. Washington couldn't compete with these modern facilities.

Racial Changes in D.C.

A factor rarely discussed openly at the time involved the changing racial makeup of Washington. The city's population was becoming predominantly African American by the late 1950s.

Calvin Griffith later made infamous comments suggesting racial demographics influenced his decision to move the team to the predominantly white Twin Cities. While other factors certainly played major roles, the racial attitudes of the time cannot be dismissed as a contributing factor.

1933 World Series Disappointment

In the 1933 World Series, Washington faced the New York Giants, the same team they had beaten in 1924. This time, the result was different. The Giants, led by Carl Hubbell's brilliant pitching, took the Series in five games.

The Senators managed just 15 runs in the five games, as Hubbell and his teammates shut down Washington's offense. The championship magic of 1924 couldn't be recaptured.

THE EXPANSION SENATORS: A BRIEF ENCORE

Baseball Returns to D.C. (1961)

When the original Senators moved to Minnesota after the 1960 season, Major League Baseball quickly awarded Washington an expansion team to begin play in 1961. These new Senators, technically a different franchise from the original team, continued Washington's baseball tradition.

Unfortunately, they also continued Washington's losing tradition. The expansion Senators never finished above .500 in their 11 seasons in D.C.

The Short-Lived Return

Despite having a few stars, most notably slugger Frank Howard (OF, WSH), the new Senators couldn't build a winner. By 1971, owner Bob Short had decided to move the team. After the 1971 season, they relocated to Arlington, Texas, becoming the Rangers.

Washington would remain without Major League Baseball from 1972 until 2005, when the Montreal Expos moved to D.C. and became today's Washington Nationals.

THE WASHINGTON BASEBALL LEGACY

A City's Baseball Heritage

Washington's baseball story isn't just about losing teams and departing franchises. It's about a city that loved the game despite decades of disappointment.

From Walter Johnson's fastball to Goose Goslin's swing, from the 1924 World Series triumph to the heartbreak of two teams leaving town, Washington's baseball heritage is rich and complex.

The success of today's Nationals helps heal old wounds. Their 2019 World Series championship gave Washington fans their first baseball title since 1924, a span of 95 years.

But for those who remember the original Senators, there will always be something special about Walter Johnson pitching in relief in Game 7 of the 1924 World Series, finally winning the championship that had eluded him for so long.

That moment—perhaps the greatest in Washington sports history—remains the perfect symbol of a city's long, often frustrating, but occasionally glorious baseball journey.