The Polo Grounds: Where Baseball History Lived and Breathed

Nine Moments That Defined a Ballpark · 1905 – 1954

Coogan's Hollow, Upper Manhattan · New York City · Est. 1880 · Demolished April 1964

Note: the timeline interactive is causing a miscalculation on read time for this article. The correct read time is eight minutes.

There are ballparks, and then there is the Polo Grounds. No stadium in baseball history witnessed more drama, more heartbreak, or more brilliance than that old horseshoe-shaped fortress at the foot of Coogan's Bluff in Upper Manhattan. For more than eight decades, it stood as the beating heart of New York baseball, and in many ways the beating heart of the sport itself. When it finally fell to the wrecking ball in 1964, baseball lost one of its true irreplaceable shrines.

A Stadium That Kept Reinventing Itself

The Polo Grounds was really four different stadiums that shared the same name and the same baseball soul.

The original opened in 1876 as an actual polo field, sitting north of Central Park between 110th and 112th Streets. The New York Metropolitans converted it to a baseball stadium in 1880, with the New York Gothams joining them in 1883. The Gothams would soon be renamed the Giants. The two teams literally shared the field, with separate diamonds laid out side by side. That first Polo Grounds held about 12,000 fans. It would not survive the decade. New York City's northward expansion required extending West 111th Street straight through the outfield, and after the Giants' last game there on October 13, 1888, the old park was gone.

The Giants landed in 1891 at Coogan's Hollow at 155th Street, where the final and most famous version would eventually rise. That structure grew steadily through the 1890s and into the new century. By 1911, capacity had reached 31,000, making it the largest stadium in baseball. Then, on April 14, 1911, fire destroyed most of the wooden structure. Owner John T. Brush hired architect Henry Beaumont Herts and ordered him to build something magnificent. In just 11 weeks, a new stadium of steel, concrete, and marble rose from the ashes. It reopened on June 28, 1911. Brush tried to rename it Brush Stadium. Nobody called it that. It was the Polo Grounds, and the Polo Grounds it stayed.

That final version served baseball from 1911 through 1957 with the Giants, then hosted the expansion New York Mets in 1962 and 1963 before its final game on September 18, 1963. The wrecking ball arrived in April 1964. Public housing towers, known today as the Polo Grounds Towers, stand on the site.

A Shape Unlike Any Other

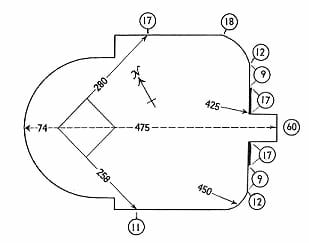

What made the Polo Grounds unlike any other park in baseball was its extraordinary shape. Writers at the time called it a bathtub. Others compared it to a horseshoe. Both descriptions fit.

The foul lines were absurdly short. The left field line measured just 279 feet. Right field was even shorter at 257 feet, barely a long flyball from home plate. Mel Ott exploited that short right-field porch for his entire career, lifting that famous high leg kick and driving ball after ball into the seats.

Then there was center field. The distance to the wall was a staggering 483 feet, and during some configurations it stretched even deeper. Only four men ever cleared that wall. Luke Easter of the Negro Leagues did it in 1948, Joe Adcock in 1953, and Lou Brock and Hank Aaron on consecutive days in June 1962.

The grandstand rose in a sweeping horseshoe curve from the left-field corner around home plate to right field, with an upper and lower deck along both baselines. The upper deck facade featured ornate bas-relief carvings of all eight National League team emblems. The clubhouses sat beyond the center-field wall, meaning players had to walk across the entire outfield before and after games. Fans on Coogan's Bluff, the rocky rise above left field, could watch for free. Generations of New Yorkers who could not afford a ticket did exactly that.

The Teams That Called It Home

The Polo Grounds was primarily the home of the New York Giants from 1883 through their departure to San Francisco after the 1957 season. But the stadium housed some notable tenants along the way.

The New York Yankees played there from 1913 through 1922 while Yankee Stadium was being built. Babe Ruth called it home during those years, including both the 1921 and 1922 World Series, each played entirely at the Polo Grounds. John McGraw had no love for the American League, and he made the Yankees unwelcome tenants. When they finally moved to their own house in 1923, McGraw's relief was palpable.

The New York Mets occupied the Polo Grounds for their first two seasons in 1962 and 1963 while Shea Stadium was being completed. The Mets lost 120 games in 1962, a modern record for futility, but the old park kept National League baseball alive in New York while a new era took shape.

The New York Cubans of the Negro National League also called the Polo Grounds home for most seasons between 1935 and 1950. They brought some of that era's finest players to the same grounds where Willie Mays would later make history.

The Top 9 Moments That Defined the Polo Grounds

The events that unfolded within those odd-shaped walls could fill several books. Here are the ten that stand above the rest.

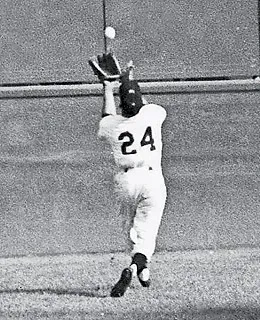

1. The Catch (1954)

Game 1 of the 1954 World Series produced what most fans and historians consider the single greatest defensive play in baseball history. The score was tied 2-2 in the eighth inning when Vic Wertz drove a pitch toward the deepest part of center field. Willie Mays turned his back to the plate and ran, flat out and full speed, toward the warning track. At roughly 460 feet from home plate, he caught the ball over his shoulder without breaking stride. Then he spun and fired back to the infield. The Giants won in the tenth on Dusty Rhodes' pinch-hit homer and swept the heavily favored Indians four games to none. But it was that one play in the eighth inning that people remember. Some things in this game are simply perfect, and The Catch was one of them.

2. Shot Heard 'Round the World (1951)

On August 11, 1951, the Giants trailed the Brooklyn Dodgers by 13½ games. What happened next remains the most stunning comeback in baseball history. The Giants won 37 of their final 44 games to force a three-game playoff. Brooklyn led 4-1 heading into the bottom of the ninth in the decisive third game. The Giants scratched out a run and had two men on base when Bobby Thomson came to the plate against Ralph Branca. Thomson drove the pitch into the short left-field stands for a walk-off three-run homer. On the radio, Russ Hodges screamed "The Giants win the pennant!" so many times the recording became an American landmark. The pitch, the swing, the call. No single moment in baseball history has been replicated since.

3. Christy Mathewson's Three World Series Shutouts (1905)

In the 1905 World Series against the Philadelphia Athletics, Mathewson pitched three complete-game shutouts in six days. He went 27 innings, allowed just 13 hits, walked one batter, and struck out 18. His ERA for the Series was 0.00. Every single game was a shutout, a record that has never been matched and never will be. Connie Mack, who managed against Mathewson that October, later said he was simply the greatest pitcher who ever lived. Nothing from 1905 contradicts that.

4. John McGraw's Four-Year Dynasty (1921-1924)

For four consecutive years, the New York Giants won the National League pennant. It was the longest stretch of sustained excellence in franchise history. The 1921 and 1922 World Series were played entirely at the Polo Grounds, as the Giants faced their own stadium tenants, the Yankees, both times. McGraw won both. The Giants took the 1921 Series in eight games, then swept the Yankees in 1922. They fell short in 1923 and 1924, but those four straight pennants represented the last dynasty the Giants would produce in New York. McGraw ran the Polo Grounds like a general who had never known another command.

5. Merkle's Boner (1908)

September 23, 1908, was the day a 19-year-old rookie named Fred Merkle made a baserunning mistake that cost the Giants the pennant. With two out in the ninth and a runner on first, Al Bridwell singled what appeared to be the winning run home. Merkle headed for the clubhouse without touching second base. Cubs second baseman Johnny Evers retrieved the ball and stepped on second. Umpire Hank O'Day called Merkle out and nullified the run. The game was declared a tie. When the Giants and Cubs finished deadlocked in the standings, the game was replayed and the Cubs won, taking the pennant and eventually the World Series. Merkle played another 16 years in the majors. He was never allowed to forget that one afternoon at the Polo Grounds.

6. Ray Chapman (1920)

The darkest day in the stadium's history came on August 16, 1920. Cleveland shortstop Ray Chapman stepped in against Yankees pitcher Carl Mays, a man known for his submarine delivery and his willingness to pitch inside. Mays threw, and the ball struck Chapman in the left temple. The sound, witnesses said, was sickening. Chapman collapsed and was carried from the field. He died early the next morning, August 17, becoming the only player in major league history to die from an in-game injury. He was 29 years old. The tragedy eventually contributed to the mandatory use of batting helmets. At the Polo Grounds that August afternoon, the sport lost its innocence about the dangers it harbored.

7. Carl Hubbell's Five Consecutive Hall of Fame Strikeouts (1934)

The 1934 All-Star Game gave baseball one of its most astonishing pitching performances. Carl Hubbell took the mound and struck out five straight American League batters: Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Jimmie Foxx, Al Simmons, and Joe Cronin. In order. All five are in the Baseball Hall of Fame. Hubbell did not nibble or try to survive. He attacked. Nobody walked out of the Polo Grounds that day without knowing they had witnessed something that would never happen again.

8. The 1921 and 1922 All-Polo Grounds World Series

No stadium in baseball history ever hosted an entire World Series, let alone two in a row. The Polo Grounds did exactly that. In both 1921 and 1922, the Giants and Yankees shared the ballpark, so every game of each Fall Classic was played under the same roof. The 1921 Series saw the Giants rally from two games down to win five games to three. In 1922, the Giants swept with a tie game mixed in, holding Ruth to a .118 average. McGraw then evicted the Yankees at season's end, forcing them to build their own park across the Harlem River. The house that Ruth built exists because McGraw showed him the door.

9. Mel Ott's 500th Home Run (1945)

On August 1, 1945, Mel Ott became the first National Leaguer in history to hit 500 career home runs. Master Melvin spent his entire career exploiting that 257-foot right-field line. But the Polo Grounds was not merely a crutch. He hit 270 of his 511 career home runs on the road, proof that his power was genuine. He led the National League in home runs six times and drove in 1,860 runs over 22 seasons, all in one uniform. When he retired in 1947, only Babe Ruth and Jimmie Foxx had hit more home runs in major league history.

Gone, But Not Forgotten

The Polo Grounds sat empty and decaying after the Mets left in September 1963. The wrecking balls arrived the following April. By the time they finished, nothing remained of the old horseshoe but memories.

From Mathewson's mastery in 1905 to Mays' impossible catch in 1954, the Polo Grounds served as the setting for baseball at its absolute best. From Merkle's misfortune in 1908 to Thomson's thunderbolt in 1951, it captured the game at its most human. It was a place built for drama, with peculiar dimensions that invited the unexpected at every turn.

The Polo Grounds Towers now rise from Coogan's Hollow. Most New Yorkers passing by have no idea what once stood there. But for anyone who loves this game and its history, that old address at 155th Street and Eighth Avenue still echoes with the crack of the bat. Some places just matter more than others. The Polo Grounds was that kind of place.