Bill Veeck: Baseball's Greatest Showman

Bill Veeck remains one of baseball's most colorful characters. As owner of the Cleveland Indians, St. Louis Browns, and Chicago White Sox (twice), Veeck brought innovation, fun, and occasionally outrage to America's pastime. Here are 13 unforgettable stories from his remarkable career.

The Ivy on Wrigley's Walls

Long before he owned his first team, Veeck made his mark on baseball history. As a 23-year-old working for his father, who was president of the Chicago Cubs, young Bill suggested planting ivy on Wrigley Field's brick outfield walls in 1937.

"The walls looked terrible," Veeck recalled years later. "Just bare brick that gave the park an unfinished look."

Veeck personally planted the bittersweet and Japanese ivy that became one of baseball's most iconic features. Today, Wrigley's ivy-covered walls remain perhaps the most recognizable feature of any American sports venue. Not bad for a young man's first contribution to baseball.

Ownership on a Shoestring

In 1946, Veeck purchased the Cleveland Indians despite having little money. He scraped together $500,000 from various investors - about $7.5 million in today's dollars, a fraction of what MLB teams cost now.

"I figured you didn't need money to run a ballclub," Veeck said. "You needed fans."

Veeck used a $25,000 insurance policy on his wooden leg (lost in WWII) as part of his collateral for the purchase. When his partners questioned his unconventional financing, Veeck replied, "If things go bad, I can always cut off my leg and collect."

Eddie Gaedel: The 3'7" Pinch Hitter

Perhaps Veeck's most famous stunt came on August 19, 1951. As owner of the struggling St. Louis Browns, Veeck sent 3-foot-7-inch Eddie Gaedel to pinch hit against the Detroit Tigers. Wearing uniform number "1/8," Gaedel crouched at the plate with a strike zone just 1.5 inches tall.

Tigers pitcher Bob Cain couldn't help laughing but then threw four straight balls. Gaedel walked to first base and was replaced by a pinch runner.

"He was the best darn ballplayer I ever owned," Veeck joked. "He had a perfect on-base percentage."

American League president Will Harridge was furious, calling the stunt "a mockery of the game," and banned Gaedel from baseball the next day. But fans loved it, and it remains one of baseball's most memorable moments.

Grandstand Managers Day

On August 24, 1951, Veeck introduced "Grandstand Managers Day" where fans actually made the strategic decisions during a game. About 1,000 fans received "YES" and "NO" cards and collectively voted on decisions like whether to bunt, steal, or change pitchers.

Browns manager Zack Taylor sat in a rocking chair in the dugout reading a newspaper while the fans called the shots. Remarkably, the fan-managed Browns beat the Philadelphia Athletics 5-3 that day.

"The fans outsmarted Connie Mack, which just proves anybody can manage," Veeck quipped after the game.

Exploding Scoreboard

When Veeck bought the Chicago White Sox in 1959, he installed baseball's first "exploding" scoreboard at Comiskey Park. After White Sox home runs, the $300,000 scoreboard erupted with fireworks, sound effects, and flashing lights.

"Baseball is entertainment," Veeck said. "If someone wants to pay me to watch baseball, I should give them something worth seeing."

Other owners complained the scoreboard distracted opposing pitchers, but fans loved the spectacle. Today, nearly every MLB stadium features some version of Veeck's innovation, with elaborate home run celebrations considered standard.

Bermuda Shorts Uniform

Of all Bill Veeck’s fan-focused innovations, perhaps none was more infamous or player-despised than the Bermuda shorts uniform. During his second ownership tenure with the Chicago White Sox in the mid-1970s, Veeck and his wife, Mary Frances, sought a solution to the brutal Chicago summer heat. Their answer, unveiled on August 8, 1976, for a doubleheader against the Kansas City Royals, was a radical uniform design featuring large, floppy-collared jerseys and, most shockingly, navy blue Bermuda shorts. Veeck’s logic was simple: if golfers and tennis players could wear shorts for comfort, why not baseball players?

The reaction was immediate and overwhelmingly negative. Players were mortified, feeling unprofessional and ridiculous. Outfielder Ralph Garr famously quipped, "You can't slide in shorts," while others worried about exposing their legs to scrapes and bruises. The media and opposing teams had a field day, mercilessly mocking the "South Side Hitmen" for looking more like a beer-league softball team. While the stunt generated immense publicity, it was almost entirely ridicule. The players' rebellion was so strong that the shorts made only two more appearances that month before being permanently retired. Despite the team winning two of the three games they played in them, the shorts went down in history as a step too far, even for baseball’s greatest showman. It perfectly encapsulated the Veeck ethos: a willingness to defy every tradition for the sake of comfort and buzz, even if it meant his own players wanted to hide in the dugout from embarrassment.

Signing Larry Doby

While Jackie Robinson rightfully gets credit as MLB's first Black player in the modern era, Larry Doby broke the American League color barrier just 11 weeks later when Veeck signed him to the Cleveland Indians in July 1947.

Unlike Branch Rickey's calculated, years-long plan with Robinson, Veeck made the Doby signing happen in days. He quietly purchased Doby's contract from the Newark Eagles of the Negro Leagues for $15,000, then announced the signing with little fanfare.

"Why all the noise about signing a ballplayer?" Veeck asked reporters. "I just signed a guy who can help us win."

Doby faced similar discrimination as Robinson but with less media support. He persevered to become a seven-time All-Star and helped Cleveland win the 1948 World Series.

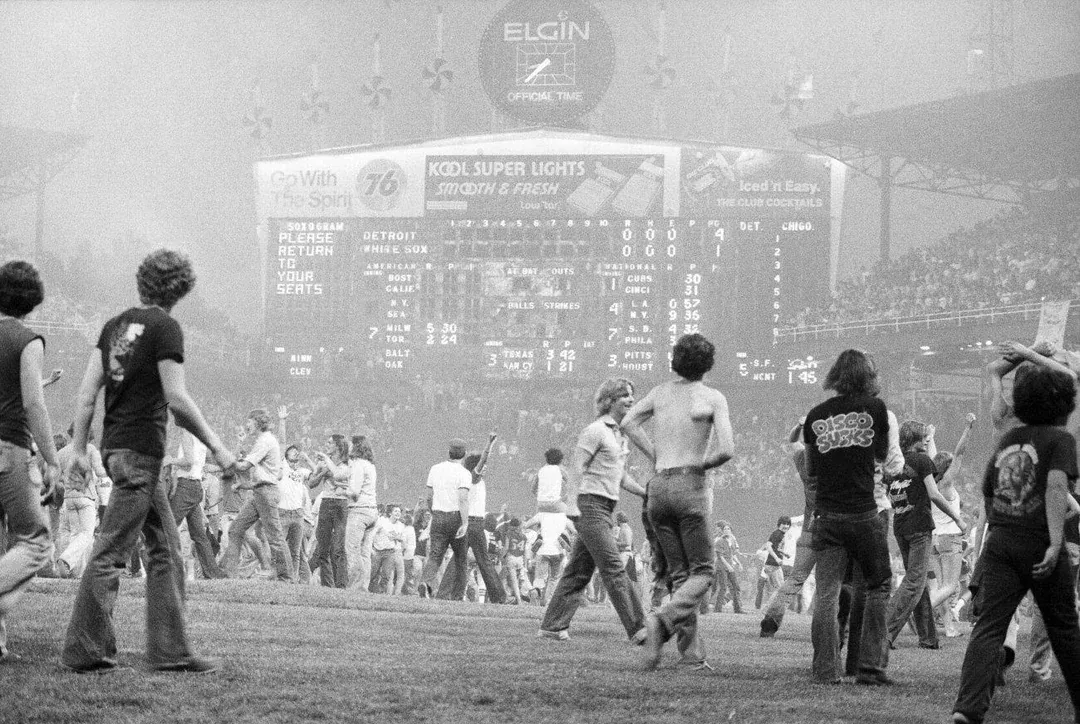

Disco Demolition Night

Not all of Veeck's promotions succeeded. The infamous "Disco Demolition Night" on July 12, 1979, at Comiskey Park stands as his most disastrous idea.

Fans were offered 98-cent tickets if they brought disco records to be blown up between games of a doubleheader against the Detroit Tigers. Instead of the expected 20,000 fans, nearly 50,000 packed the stadium with another 20,000 outside trying to get in.

When local DJ Steve Dahl detonated a box of records in center field, thousands of fans rushed onto the field. The riot left the field unplayable, forcing the White Sox to forfeit the second game.

"It was a mistake," Veeck admitted years later. "We underestimated the anger people had toward disco."

Signing Satchel Paige

In 1948, Veeck signed 42-year-old Negro Leagues legend Satchel Paige to the Cleveland Indians. Many called it a publicity stunt, but Paige went 6-1 with a 2.48 ERA, helping Cleveland win the World Series.

When critics questioned Paige's age, Veeck responded: "How old would you be if you didn't know how old you were?"

Twelve years later, at age 59, Veeck brought Paige back for one game with the Kansas City Athletics in 1965. Paige pitched three scoreless innings against the Boston Red Sox, allowing just one hit.

"Age is a question of mind over matter," Veeck said. "If you don't mind, it doesn't matter."

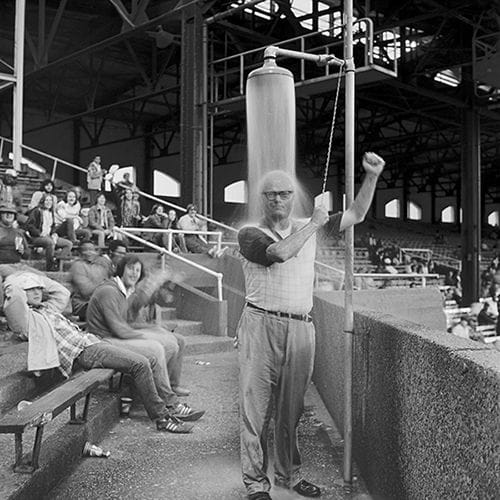

Shower Night

Veeck understood the Chicago summer heat made Comiskey Park uncomfortable. His solution? An outdoor shower in the center field bleachers where fans could cool off during games.

"Baseball should be fun, not torture," Veeck said. "If people are hot, let them cool off and enjoy the game."

The shower became so popular that Veeck added "Shower Night" promotions where fans in bathing suits got in free if they watched from the shower area. Other owners considered it undignified, but White Sox attendance increased despite the team's poor record.

Free Pregnancy Tests

When Veeck owned the St. Louis Browns in the early 1950s, he tried everything to draw fans to watch baseball's worst team. One of his most outrageous but little-known promotions: offering free pregnancy tests to women at the ballpark.

"We couldn't promise good baseball," Veeck explained, "but we could provide useful services."

The promotion lasted just one game before baseball commissioner Ford Frick shut it down, calling it "inappropriate for a family setting." Veeck's response: "Baseball is a family business. What's more family-oriented than helping people start families?"

Putting Player Names on Uniforms

Today it’s standard, but in 1960 it was a revolution. With the White Sox, Veeck became the first owner to add player names to the back of the jerseys. His reasoning was simple and entirely fan-focused: he wanted the fan in the last row of the upper deck to know who they were watching without a program.

Other owners initially derided the move as a "bush-league" tactic that cluttered the classic uniform. But the innovation was so popular with fans that, within a decade, nearly every team had adopted it. It was a simple, brilliant idea that put the fan experience first.

The Wooden Leg Anecdotes

Veeck lost his right leg below the knee from an injury sustained serving with the Marines in World War II, but he never let it define him. Instead, he treated his prosthesis with a legendary lack of sentimentality. He was known to carve holes into his wooden leg to use as a makeshift ashtray during long meetings.

He would often shock people by propping the leg up on a desk or pulling up his pant leg to make a point. When a reporter once asked him how he dealt with the daily inconvenience, Veeck shot back with his typical wit, "I don't have to worry about my feet getting cold." His humor and resilience were as much a part of his character as his showmanship.

Bill Veeck died in 1986, leaving behind a legacy of innovation and entertainment. While many of his ideas seemed crazy at the time, numerous Veeck innovations are now baseball standards: exploding scoreboards, player names on uniforms, regular promotional giveaways, and more.

"Baseball is a game to be enjoyed," Veeck once said. "Too many people forget that."

He made sure fans never did.