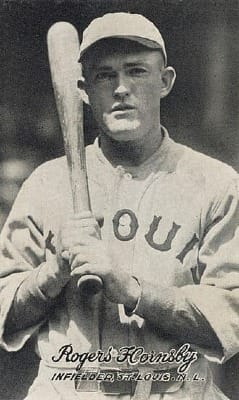

By the Numbers: Hornsby's Statistical Legacy (Part 2)

Beyond the traditional statistics and advanced metrics already discussed, several statistical oddities highlight just how extraordinary Hornsby's career was:

• Hornsby is the only player in MLB history to hit .400 with 40+ home runs in the same season (1922: .401, 42 HR).

• His .424 batting average in 1924 is the highest single-season mark in National League history.

• After winning the batting title with a .370 average in 1920, Hornsby embarked on an unprecedented five-year tear, hitting .397, .401, .384, .424, and .403.

• From 1921 to 1925, Hornsby led the National League in batting average, on-base percentage, slugging percentage, OPS, and OPS+ every single year – a five-year sweep of the slash-line categories unmatched in baseball history.

• Hornsby's career .577 slugging percentage is higher than Hank Aaron's (.555) and Willie Mays' (.557).

• Despite playing in the early live-ball era, Hornsby's 301 career home runs ranked 11th all-time when he retired.

• Among players with at least 8,000 plate appearances, Hornsby's .358 career batting average trails only Ty Cobb's .366.

• Hornsby hit over .400 three times in his career. In MLB history, only Ty Cobb matched this feat.

• In 1925, Hornsby led the NL with 39 homers while striking out just 39 times – a 1:1 HR/K ratio that seems impossible by modern standards.

His peak from 1921-1925 produced a five-year slash line of .402/.474/.690, resulting in a 1.164 OPS and 202 OPS+. For context, Mike Trout's best five-year run produced a 1.000 OPS and 176 OPS+.

"Statistics can't fully capture greatness," baseball writer Roger Angell once wrote, "but in Hornsby's case, they come closer than for almost anyone else."

The What-Ifs: Hornsby in Modern Context

When evaluating Hornsby's career, several "what-ifs" emerge that make his accomplishments even more impressive:

What if Hornsby played in a hitter-friendly park? Unlike many great hitters of his era, Hornsby didn't benefit from a particularly favorable home park. Sportsman's Park in St. Louis had fairly neutral dimensions. Had he played in the Baker Bowl (like Chuck Klein) or Fenway Park, his numbers might have been even more astronomical.

What if Hornsby had modern training methods? Hornsby built his physique through farm work and basic exercise. With modern strength training, nutrition, and recovery methods, his power numbers might have reached even greater heights.

What if Hornsby played in integrated baseball? This is a complex counterfactual. While Hornsby would have faced a deeper talent pool in an integrated league, potentially lowering his numbers, he also would have had the opportunity to prove his skills against the complete spectrum of baseball talent.

What if Hornsby had played his entire career with one team? Hornsby's constant team changes likely hurt his overall production and legacy. Had he stayed with the Cardinals for his entire career, his counting stats and team success might have been even more impressive.

The Final Verdict: Hornsby's Place in Baseball History

So where does Rogers Hornsby rank in baseball history? The answer depends somewhat on how we weigh different factors, but a few conclusions seem inescapable:

- Hornsby is unquestionably the greatest second baseman in baseball history. The statistical gap between him and other great second basemen is larger than at any other position.

- Hornsby ranks among the greatest right-handed hitters ever, alongside Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, Albert Pujols, and Mike Trout.

- When considering peak performance, Hornsby's 1921-1925 stretch stands with any five-year period in baseball history, including Ruth's best years, Bonds' early 2000s, and Williams' dominant stretches.

- Hornsby's personality issues and defensive limitations prevent him from ranking at the very top of the all-time list, but his offensive brilliance places him comfortably in the top 15-20 players ever.

Bill James ranked Hornsby as the 9th greatest player in baseball history in his Historical Baseball Abstract. Baseball Reference's WAR leaderboard places him 9th among position players all-time.

"If you're building an all-time team," Joe Posnanski wrote in The Baseball 100, "and you don't have Hornsby at second base, you're doing it wrong."

While modern fans may not immediately recognize Hornsby's name the way they do Ruth's, Mays', or Aaron's, his statistical legacy ensures that serious baseball historians and analysts will always place him among the game's immortals.

Rogers Hornsby was difficult. He was abrasive. He made enemies everywhere he went. But when he stepped into the batter's box, he was nothing short of genius. As teammate Frankie Frisch put it: "Hornsby was a pain in the neck, but boy, could he hit that baseball."

Nearly a century after his prime, no second baseman has come close to matching The Rajah's offensive brilliance. And given the specialized nature of modern baseball, it's likely none ever will.

The Prickly Rajah: How Hornsby's Personality Shaped His Career

Rogers Hornsby could hit a baseball like few in history. He could also clear a room faster than anyone in the game.

"Hornsby never met a teammate he couldn't insult," said longtime Cardinals pitcher Jesse Haines. "He'd tell you exactly what he thought, even if you didn't ask him."

While Hornsby's bat made him indispensable to teams, his personality created a wake of burnt bridges that followed him throughout his career. Let's examine how The Rajah's abrasive character affected his relationships with teammates and ultimately shaped his unusual career path.

"I'm Not Here to Make Friends"

Hornsby had a simple philosophy about teammates: he wasn't there to socialize. Baseball was a job, and his co-workers were just that – people who happened to work at the same place he did.

"I don't pay attention to whether players like me or not," Hornsby once said. "I'm paid to hit the ball, not to make friends."

This business-only approach might have been tolerable if Hornsby had kept to himself. But he combined his disinterest in friendship with a brutal honesty that alienated nearly everyone around him.

Cardinals outfielder Taylor Douthit recalled a typical Hornsby interaction: "I asked him for hitting advice as a rookie. He looked at me and said, 'Kid, the way you swing, you'll be lucky to hit .220 in this league.' No hello, no encouragement – just the cold truth as he saw it."

Even his managers weren't spared. When Cardinals manager Branch Rickey suggested a hitting adjustment, Hornsby reportedly responded: "Mr. Rickey, I hit .370 last year. When you hit .370, you can tell me how to hit."

The Anti-Social Ballplayer

While baseball teams of the 1920s were known for their carousing and night life, Hornsby wanted no part of it. He didn't drink, smoke, or go to movies (to protect his eyesight). He didn't join teammates for meals or social outings. He rarely even sat with them in the dugout, preferring to keep to himself.

"Rogers was the loneliest man I ever saw in baseball," said Cardinals teammate Specs Toporcer. "He'd sit alone on the bench, alone on trains, alone at the hotel. Nobody dared approach him."

This self-imposed isolation might have been acceptable to teammates if Hornsby hadn't simultaneously criticized their lifestyle choices. He routinely berated players who stayed out late or showed up with hangovers. When he became player-manager of the Cardinals, he implemented strict rules about curfews and drinking that were unpopular with the team.

"The boys resented his holier-than-thou attitude," said Cardinals outfielder Ray Blades. "He'd lecture us about taking care of ourselves, then wonder why nobody wanted to be around him."

The Player-Manager Problem

Hornsby's teammate issues intensified when he became player-manager of the Cardinals in 1925. Now his judgments and criticisms carried real consequences – playing time, job security, and money.

"As a teammate, you could ignore Hornsby," said Cardinals pitcher Bill Sherdel. "As your manager, you had to deal with him, and that wasn't easy for anybody."

Hornsby managed as he played – with brutal honesty and no concern for feelings. If a player made a mistake, Hornsby would call him out publicly. If a pitcher wanted to stay in a game, Hornsby would tell him exactly why he wasn't good enough to continue.

Despite these issues, the Cardinals won the 1926 World Series under Hornsby's leadership. But the victory celebration demonstrated just how disconnected he was from his team. While players celebrated in the clubhouse, Hornsby quietly changed and left without joining the party.

"We won the World Series, and our manager didn't even stick around to celebrate," recalled Cardinals infielder Jimmy Cooney. "That tells you everything about Rogers."

The Cubs Mutiny

Perhaps the most telling example of Hornsby's teammate relationships came during his time with the Chicago Cubs. In 1932, as player-manager, he alienated his team so thoroughly that they essentially revolted against him.

"Hornsby rode us constantly," Cubs outfielder Riggs Stephenson later recalled. "Nothing was ever good enough. He'd fine players for the smallest mistakes and berate them in front of the team."

The situation came to a head in August 1932, when Cubs players approached owner William Wrigley and demanded Hornsby's removal. Wrigley, to his credit, listened to his players and fired Hornsby despite the team being in contention.

The real gut punch came after the season. When the Cubs won the pennant under replacement manager Charlie Grimm, the team voted 19-4 against giving Hornsby a World Series share – despite his having managed the team for two-thirds of the season. It was an unprecedented rejection by teammates.

"That vote told the baseball world what the Cubs players thought of Hornsby," wrote baseball historian Harold Seymour. "They'd rather give up money than reward a man they couldn't stand."

The Foxx Contrast

Jimmie Foxx, Hornsby's contemporary and fellow Triple Crown winner, provides an instructive contrast in how personality affected teammate relationships. Foxx was universally liked – a friendly, supportive teammate despite being one of the game's biggest stars.

"Everyone loved Double X," said Athletics teammate Doc Cramer. "He'd take young players under his wing, celebrate their successes, and never act like he was better than anyone."

When Foxx was traded, teammates expressed genuine sadness. When Hornsby was traded, teammates often celebrated. After Hornsby was dealt from the Giants to the Braves in 1928, Giants first baseman Bill Terry reportedly said: "The best trade McGraw ever made was getting rid of Hornsby."

This personality difference likely contributed to their divergent career paths. Foxx played 14 of his 20 seasons with the Philadelphia Athletics, becoming a beloved franchise icon. Hornsby bounced between seven teams in seven seasons during his prime, never establishing a lasting home despite his superior statistics.

"The Truth as I See It"

Hornsby never apologized for his abrasive nature. He saw himself as simply honest in a world of phonies.

"I don't believe in patting a man on the back just to make him feel good," Hornsby once explained. "I tell them the truth as I see it. If they don't like it, that's their problem."

This unfiltered approach occasionally found admirers. Frankie Frisch, despite having a complicated relationship with Hornsby, admitted: "You always knew where you stood with Rogers. He'd insult you to your face rather than behind your back, which had a certain integrity to it."

But most players found Hornsby's "honesty" unnecessarily cruel. As Cubs pitcher Charlie Root put it: "There's telling the truth, and then there's being mean about it. Hornsby specialized in the latter."

The Generational Divide

Interestingly, many younger players who never played with Hornsby but received hitting instruction from him late in his life had much more positive experiences. After his managing career ended, Hornsby worked as a hitting coach and instructor, where his blunt assessments were received differently.

Ted Williams, who worked with Hornsby on hitting, said: "Rogers Hornsby was the only man who talked hitting with me that I listened to with 100 percent conviction."

Mickey Mantle similarly appreciated Hornsby's directness: "He told me my stance was all wrong, that I was swinging too hard, and that I'd never reach my potential the way I was hitting. It stung, but he was right."

This suggests that Hornsby's personality wasn't inherently toxic – it was the combination of his bluntness with his position as teammate and manager that created problems. When the power dynamic changed to teacher-student rather than peer-to-peer, his approach became more palatable.

The Statistical Impact

How much did Hornsby's personality issues cost him? While impossible to quantify precisely, we can make some educated guesses:

Shortened managerial career: Despite tactical knowledge and baseball intelligence, Hornsby's interpersonal issues limited him to just 15 partial seasons as manager.

Reduced playing time late in career: Teams became less willing to tolerate Hornsby's personality as his skills declined. He was out of regular playing time by age 35 despite still being an above-average hitter.

Constant team changes: From 1927 to 1933, Hornsby played for five different teams. Each trade meant adjusting to new teammates, ballparks, and managers – likely hurting his performance.

Limited endorsement opportunities: Despite being arguably the game's best player, Hornsby received few endorsement deals compared to more personable stars like Babe Ruth.

Baseball statistician Bill James has suggested that Hornsby's difficult personality cost him approximately 500 hits and potentially 15-20 WAR over his career – the difference between being the 9th greatest position player ever (his current rank by WAR) and potentially the 3rd or 4th.

The Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

The greatest irony of Hornsby's career is that his personality issues created a self-fulfilling prophecy. His belief that he needed to focus solely on hitting – avoiding teammates, socializing, and anything that might distract him – may have actually undermined his longevity and total statistical output.

"Hornsby's approach created a paradox," wrote baseball historian Donald Honig. "His singular focus on hitting made him the greatest right-handed batter ever, but his resulting isolation created conditions that ultimately shortened his career."

Modern sports psychology emphasizes team chemistry and mental well-being as factors in athletic performance and longevity. Hornsby's approach – maximizing short-term performance at the expense of relationships – ultimately may have been counterproductive to his career goals.

"I sometimes wonder what Hornsby might have accomplished with even a modicum of people skills," said baseball writer Jerome Holtzman. "He might have been not just one of the greatest ever, but the greatest."

Lessons from Hornsby

What can today's players learn from Hornsby's relationship struggles? Several lessons stand out: Technical excellence doesn't excuse poor behavior. Despite Hornsby's incredible talent, his teams repeatedly decided they could live without him. Even the greatest players need to maintain workable relationships.

Honesty requires tact. Hornsby's commitment to "telling it like it is" lacked the crucial element of knowing when and how to deliver criticism constructively.

Team chemistry matters. The Cubs' improvement after Hornsby's departure in 1932 suggests that team cohesion and morale can significantly impact performance.

Modern players with reputation for bluntness – like former pitcher Curt Schilling or infielder Chase Utley – learned to balance honesty with relationship management in ways Hornsby never mastered.

The Final Summary

Rogers Hornsby remains baseball's greatest second baseman despite his personality flaws. His statistical case is simply too overwhelming to argue otherwise. But his legacy is complicated by the trail of damaged relationships he left behind.

"If baseball were purely an individual sport, Hornsby might be considered the greatest player ever," baseball historian John Thorn has noted. "But baseball is fundamentally a team game, and Hornsby never quite grasped that part of it."

Perhaps Hornsby's former teammate Burleigh Grimes put it best: "Rogers Hornsby was the best right-handed hitter who ever lived. He was also the worst teammate I ever had. Both things can be true at once."

The paradox of Rogers Hornsby – baseball genius, relationship disaster – serves as a reminder that even in a sport obsessed with individual statistics, no player truly succeeds alone.

Footnotes

- Rogers Hornsby's .358 career batting average ranks second all-time behind Ty Cobb's .366 (minimum 3,000 plate appearances). Source: Baseball Reference

- Hornsby's .424 batting average in 1924 is the highest single-season mark in National League history and the second-highest in MLB since 1900 (behind Nap Lajoie's .426 in 1901). Source: Baseball Reference

- Hornsby hit over .400 three times (1922: .401, 1924: .424, 1925: .403), a feat matched only by Ty Cobb in MLB history. Source: Baseball Reference

- Hornsby is the only player in MLB history to hit .400 or better with 40 or more home runs in the same season (1922: .401 AVG, 42 HR). Source: Baseball Reference

- Hornsby won seven batting titles, including six consecutive from 1920 to 1925. Source: Baseball Reference

- Hornsby is the only player to win the National League Triple Crown twice (1922 and 1925). Source: Baseball Reference

- Hornsby's career .577 slugging percentage ranks 15th all-time and first among second basemen. Source: Baseball Reference

- His career 175 OPS+ ranks 9th all-time among all players with at least 5,000 plate appearances. Source: Baseball Reference

- His career 173 wRC+ ranks 11th all-time among all players and first among second basemen. Source: FanGraphs

- The 1.164 OPS Hornsby produced from 1921-1925 is the highest five-year peak for any second baseman in MLB history. Source: Baseball Reference

- Hornsby's career 127.0 Wins Above Replacement (WAR) ranks 9th all-time among position players. Source: Baseball Reference

- His 73.5 WAR7 (best seven seasons) ranks 10th all-time among position players and first among second basemen. Source: Baseball Reference

- Bill James ranked Hornsby as the 9th greatest player in baseball history in his New Historical Baseball Abstract (2001 edition).

- Jeff Kent's 377 home runs are the most by a player who primarily played second base, though Hornsby's overall offensive value (by WAR, OPS+, and wRC+) remains substantially higher. Source: Baseball Reference

- Hornsby managed parts of 15 seasons with six different teams, compiling a 701-812 record (.463 winning percentage). Source: Baseball Reference

- He played for five different teams in the seven seasons from 1927 to 1933 (New York Giants, Boston Braves, Chicago Cubs, St. Louis Cardinals, and St. Louis Browns). Source: Baseball Reference

- The 1932 Chicago Cubs voted 19-4 against giving Hornsby a World Series share, despite his having managed the team for the first 117 games of the season. Source: Chicago Tribune archives, October 1932

- Under replacement manager Charlie Grimm, the 1932 Cubs improved from a .526 winning percentage under Hornsby to a .654 winning percentage for the remainder of the season. Source: Baseball Reference

- Hornsby was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1942, his fifth year on the ballot, receiving 78.1% of the vote. Source: National Baseball Hall of Fame

- Ted Williams is quoted as saying, "Rogers Hornsby was the only man who talked hitting with me that I listened to with 100 percent conviction." Source: My Turn at Bat: The Story of My Life, Ted Williams autobiography, 1969.