Dancing with Chaos: The Knuckleball and its Masters

Imagine stepping into the batter's box, your muscles coiled to unleash on a 95-mph fastball, only to face a pitch that seems to float, dance, and dive in multiple directions at once.

This is the bewildering experience of facing a knuckleball, a pitch so erratic that it has been the secret weapon for some of baseball's most enduring and unlikely stars.

"I never knew if it was going to break in or out or up or down. All I knew is that I couldn't hit it," said Mickey Mantle about facing knuckleballer Hoyt Wilhelm. The Commerce Comet crushed nearly every other pitcher he faced but hit just .136 against Wilhelm with 25 strikeouts in 66 at-bats.

The knuckleball stands as baseball's most democratic pitch—requiring neither blazing speed nor youth. It has saved careers, extended others, and even turned a few journeymen into stars. It's the ultimate baseball oddity: a pitch that works because it doesn't spin, thrown by pitchers who often couldn't break 80 mph, yet it has confounded the game's greatest hitters for over a century.

Let's explore the strange science, remarkable practitioners, and uncertain future of baseball's most unpredictable weapon.

THE PHYSICS: A PITCH THAT DEFIES SPIN

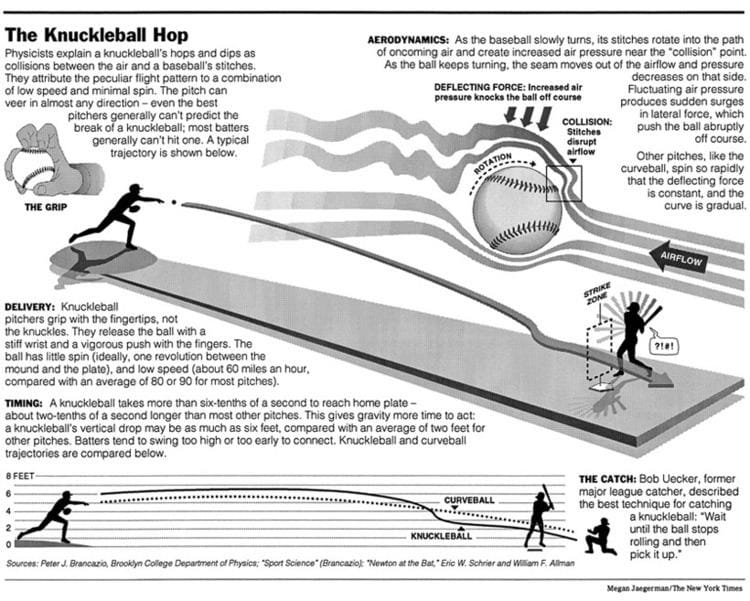

Most pitches in baseball rely on spin to create movement—curveballs spin one way, sliders another. The knuckleball, however, is the anti-pitch—it works by minimizing spin.

When thrown correctly, a knuckleball rotates less than half a turn between the pitcher's hand and home plate—about 0.25 to 0.5 rotations compared to a fastball's 15-plus rotations. This near-zero spin rate creates the pitch's signature unpredictable movement.

"A good knuckleball looks like a butterfly with hiccups," said longtime knuckleballer Tim Wakefield (RHP, BOS). The physics behind this comparison are fascinating.

Without spin to stabilize its flight, the ball becomes highly sensitive to air pressure differences created by the seams. As the ball floats toward home plate, these pressure variations push it in random directions. The slightest change in grip or release can dramatically alter the pitch's path.

The velocity of a knuckleball typically ranges from 65-75 mph—significantly slower than major league fastballs. This slowness is actually an advantage, as it gives air currents more time to act on the ball, creating more movement.

"The slower you throw it, the more it moves," explained Charlie Hough (RHP, LAD/TEX/CWS/FLA), who threw his knuckler around 65-70 mph throughout his 25-year career. "But you still have to throw it hard enough that the batter can't adjust mid-flight."

Statcast data from R.A. Dickey's (RHP, NYM/TOR) Cy Young season in 2012 showed his knuckleball averaged just 0.2-0.3 rotations between release and home plate, with a velocity around 76-77 mph. For comparison, most MLB pitches rotate 15-25 times over the same distance.

THE GRIP: FINGERNAILS, NOT KNUCKLES

Despite its name, modern knuckleballers don't actually use their knuckles to throw the pitch. Instead, they dig their fingernails into the seams of the baseball.

"I press my fingernails—index and middle fingers—against the seams, with my thumb underneath for support," explained Phil Niekro (RHP, MLN/ATL/NYY/CLE/TOR), who won 318 games with the pitch. "The trick is holding it firmly enough that you control the release, but loosely enough that it doesn't spin."

This grip creates unique challenges. Knuckleballers obsess over their fingernail length and strength. Many used nail hardeners and carried nail files in their back pockets. Tom Candiotti (RHP, MIL/CLE/LAD/OAK/TOR) was known to use clear nail polish to prevent breaks during starts.

The original knuckleball, as developed and thrown by Eddie Cicotte (RHP, DET/BOS/CHW) in the 1910s, actually did use the knuckles. Cicotte would press his knuckles against the ball to prevent spin, but this technique proved less effective than the fingernail grip that later became standard.

THE PIONEERS: EARLY KNUCKLEBALL MASTERS

The knuckleball's history begins with Eddie Cicotte, who developed the pitch around 1908. Nicknamed "Knuckles," Cicotte used the pitch to win 209 games and post a career 2.38 ERA (123 ERA+) before his involvement in the 1919 Black Sox scandal ended his career.

Dutch Leonard (LHP, BOS/DET) refined the pitch in the 1910s and 1920s, becoming one of the few successful left-handed knuckleballers. Leonard's 1914 season with Boston remains one of the greatest pitching performances ever—he went 19-5 with a modern-era record 0.96 ERA (279 ERA+) and 0.886 WHIP. Suggest adding "modern-era record" for context and updating ERA+ for accuracy.

Ted Lyons (RHP, CHW) adopted the knuckleball late in his career and rode it to the Hall of Fame. From 1939-1942, after becoming primarily a knuckleballer, Lyons posted a 3.04 ERA (143 ERA+). In his final season at age 45, he led the American League with a 2.10 ERA.

Lyons' success highlighted one of the knuckleball's great advantages—longevity. While conventional pitchers often decline in their 30s as velocity drops, knuckleballers can maintain effectiveness well into their 40s since the pitch doesn't rely on arm strength.

THE GOLDEN AGE: WILHELM AND THE KNUCKLEBALL REVOLUTIONThe post-WWII era saw the knuckleball reach new heights, spearheaded by Hoyt Wilhelm (RHP, NYG/STL/CLE/BAL/CHW/CAL/ATL/CHC/LAD). Wilhelm's journey to stardom defied convention—he didn't reach the majors until age 29 after serving in World War II, then pitched until he was 49, appearing in a then-record 1,070 games.

Wilhelm transformed what a knuckleballer could be. Previously viewed as starters who couldn't maintain velocity, Wilhelm showed the pitch could be devastating in relief. In 1952, his rookie year, Wilhelm led the National League with a 2.43 ERA (150 ERA+) while appearing in 71 games.

Over his 21-year career, Wilhelm compiled remarkable numbers: a 143-122 record, 2.52 ERA (147 ERA+), 1.125 WHIP, and saves. His 50.1 WAR ranks third all-time among relief pitchers, behind only Mariano Rivera and Dennis Eckersley.

Wilhelm's success inspired a generation of knuckleballers, including the brothers who would become the pitch's most famous practitioners.

THE BROTHERS NIEKRO: BASEBALL'S KNUCKLEBALL DYNASTY

Phil Niekro (RHP, MLN/ATL/NYY/CLE/TOR) and Joe Niekro (RHP, CHC/SDP/DET/HOU/NYY/MIN) form baseball's most successful sibling pitching duo, combining for 539 career victories—mostly with the knuckleball.

Phil, nicknamed "Knucksie," stands as the knuckleball's greatest master. His stats tell the story: a 318-274 record, 3.35 ERA (115 ERA+), 5,404 innings pitched, and 3,342 strikeouts. His 90.0 WAR ranks 12th all-time among pitchers.

What's most impressive about Phil's career wasn't just longevity—though pitching effectively until age 48 is remarkable—but his workload. From 1977-1979, in his late 30s, Niekro threw an astonishing 1,003.2 innings. In 1979, at age 40, he threw 342 innings with 23 complete games—numbers unthinkable in modern baseball.

Joe adopted the knuckleball later than Phil, switching primarily to the pitch in his 30s. The results were dramatic—after a mediocre first decade (81-85, 3.96 ERA through 1977), Joe went 123-104 with a 3.26 ERA in his final nine seasons after fully embracing the knuckler.

"Our dad taught us both the pitch when we were kids," Phil once explained. "I stuck with it from the beginning. Joe tried to throw like everyone else before coming back to what worked."

THE WORKHORSES: WOOD AND HOUGH

Wilbur Wood (LHP, BOS/PIT/CHW) and Charlie Hough (RHP, LAD/TEX/CWS/FLA) took the knuckleball's durability advantage to extreme levels.

Wood's transformation from mediocre reliever to ace starter showcases the knuckleball's career-changing potential. From 1967-1970, Wood worked exclusively in relief for the White Sox. Then, in 1971, Chicago converted him to starting. The results were staggering:

• 1971: 22-13, 1.91 ERA (189 ERA+), 334 innings, 22 complete games

• 1972: 24-17, 2.51 ERA (147 ERA+), 376.2 innings, 20 complete games

• 1973: 24-20, 3.46 ERA (116 ERA+), 359.1 innings, 21 complete games

Wood's 376.2 innings in 1972 remain the highest single-season total since 1917. His 49.6 WAR with Chicago ranks fourth in White Sox history.

Charlie Hough similarly built an ironman reputation. After starting his career as a reliever with the Dodgers, Hough became a full-time starter with Texas at age 34. He then proceeded to throw 200+ innings for seven consecutive seasons (1982-1988) with the Rangers.

Hough pitched until age 46, amassing 216 wins and 107 complete games. His career 3.75 ERA (108 ERA+) over 25 seasons illustrates the knuckleball's effectiveness across eras—Hough pitched effectively from the pitcher-friendly 1970s through the offense-heavy early 1990s.

THE MODERN MASTERS: WAKEFIELD, CANDIOTTI, AND DICKEY

The knuckleball's survival into the modern era came through three key practitioners: Tom Candiotti (RHP, MIL/CLE/LAD/OAK/TOR), Tim Wakefield (RHP, PIT/BOS), and R.A. Dickey (RHP, TEX/SEA/MIN/NYM/TOR/ATL).

Candiotti, known as "The Candy Man," kept the pitch alive through the 1980s and 1990s. While his 151-164 career record seems unimpressive, his 3.73 ERA (108 ERA+) and 42.1 WAR better reflect his effectiveness. From 1986-1993, Candiotti posted a 3.51 ERA (115 ERA+) while averaging 32 starts and 223 innings per season.

Tim Wakefield's career provides perhaps the ultimate knuckleball redemption story. Originally an infielder, Wakefield converted to pitching and reached Pittsburgh as a knuckleballer in 1992, going 8-1 with a 2.15 ERA. After struggling and being released, Boston signed him in 1995, beginning a 17-year Red Sox career that included two World Series championships.

Wakefield finished with 200 wins, a 4.41 ERA (105 ERA+), and 34.5 WAR. His versatility proved invaluable—he started, relieved, and closed at various points. In 2009, at age 42, he made his only All-Star team, showing the knuckleball's age-defying properties.

R.A. Dickey represents the knuckleball's most unlikely success story. A former first-round pick who struggled with conventional pitching, Dickey was discovered to be missing an ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) in his pitching elbow—a physical impossibility for most pitchers. Reinventing himself as a knuckleballer, Dickey's career culminated in a magical 2012 season with the Mets:

• 20-6 record, 2.73 ERA (139 ERA+), 1.053 WHIP, 230 strikeouts

• 5.7 WAR, NL Cy Young Award

Dickey became the first (and still only) knuckleballer to win the Cy Young Award. What made Dickey unique was his velocity—he threw his knuckleball harder (77-80 mph) than traditional practitioners, giving hitters even less time to react to its unpredictable movement.

THE BUTTERFLY CATCHERS: HANDLING THE KNUCKLEBALL

"Catching a knuckleball is like trying to catch a butterfly with chopsticks," said Bob Uecker, who caught Phil Niekro with the Braves. This challenge has created specialized roles for catchers throughout baseball history.

Teams with knuckleballers often carried dedicated catchers for them. The Red Sox had Doug Mirabelli specifically to catch Wakefield. Boston even executed a rare mid-season trade to reacquire Mirabelli in 2006 after his replacement, Josh Bard, allowed 10 passed balls in just five Wakefield starts.

Special equipment developed for knuckleball catchers includes oversized mitts—roughly 15-20% larger than standard catcher's gloves. Charlie O'Brien, who caught Candiotti, helped design a larger, flat-faced glove specifically for handling knuckleballs.

The statistics tell the story of this unique challenge. In 2008, when catching Wakefield, Kevin Cash allowed 18 passed balls in just 29 games—more than most catchers allow in multiple full seasons.

Josh Thole, Dickey's personal catcher with both the Mets and Blue Jays, once explained: "You can't try to catch it—you have to let it come to you and then just capture it rather than stab at it."

THE LAST RESORT: THE KNUCKLEBALL AS CAREER SAVER

Throughout its history, the knuckleball has been baseball's great equalizer—allowing pitchers with limited velocity to compete against the game's elite hitters. For many, it represented a last chance at a major league career.

R.A. Dickey was considering retirement before mastering the knuckleball. "I was 31 and had been designated for assignment for the fourth time," Dickey recalled. "The knuckleball wasn't Plan B; it was Plan Z."

Tim Wakefield had been released as a position player before converting to pitching. After early success with Pittsburgh, he was actually out of baseball before Boston signed him.

Charlie Hough didn't throw his first knuckleball professionally until his fourth minor league season, when Los Angeles pitching coach Goldie Holt suggested it after watching Hough struggle with conventional pitches.

This theme runs throughout knuckleball history—pitchers turning to the pitch when all other options have failed. It's baseball's last lifeline for [struggling] careers, offering a chance to those willing to master its peculiarities.

THE KNUCKLEBALL AND ANALYTICS: MEASURING THE UNMEASURABLE

Modern pitch tracking systems like PITCHf/x and Trackman have revolutionized baseball analysis, but the knuckleball presents unique challenges. The pitch's erratic movement sometimes confuses classification algorithms.

During R.A. Dickey's prime years, PITCHf/x occasionally classified his knuckleballs as curveballs or even changeups due to their unusual movement profiles. Analysis showed Dickey's knuckleballs could move in completely different directions despite seemingly identical release points.

One fascinating study by baseball physicist Alan Nathan analyzed the movement of Dickey's knuckleballs using high-speed cameras. The findings showed that a knuckleball can change direction multiple times during its flight to home plate—something no other pitch does. This multi-directional movement explains why even the best hitters struggle against it.

Statcast data from Dickey's knuckleballs showed average horizontal break ranging from -8.5 to +8.7 inches—meaning the pitch could dart almost a foot and a half in either direction. The vertical movement showed similar variation, from +2.3 to -9.8 inches.

"What makes the knuckleball so effective isn't just the amount of movement, but its unpredictability," explained Nathan. "Hitters can adjust to consistent break patterns, but when the same pitch might break in completely different directions, hitting becomes almost impossible."

THE CULTURAL IMPACT: KNUCKLEBALLERS IN BASEBALL LORE

Knuckleballers have always occupied a special place in baseball culture—viewed as baseball's mad scientists, practitioners of a mysterious art.

The 2012 documentary "Knuckleball!" followed Wakefield and Dickey, exploring the pitch's unique fraternity. The film highlighted how previous generations of knuckleballers actively mentor younger practitioners—Phil Niekro worked with both Wakefield and Dickey on refining their techniques.

"We're a small brotherhood," Wakefield said. "There's never been more than a few of us active at any time, so we look out for each other."

This mentorship tradition dates back decades. Hoyt Wilhelm taught Charlie Hough the knuckleball's finer points when both were with the Dodgers. Joe Niekro learned from watching his brother Phil. Tim Wakefield learned from Phil Niekro. The knowledge passes directly from one generation to the next, often outside official coaching channels.

The pitch has also penetrated popular culture. The unpredictability of the knuckleball has become a metaphor for life's uncertainties. "You never know which way a knuckleball is going to break" has become shorthand for expecting the unexpected.

THE FUTURE: A DYING ART OR WAITING FOR REVIVAL?

There was a gap in the 1940s between Lyons and the next wave. With Tim Wakefield's passing in October 2023 and R.A. Dickey's retirement after the 2017 season, major league baseball currently lacks an established knuckleball specialist for the first time in years. This raises an important question: Is the knuckleball dying out?

Several factors work against the pitch in today's game:

- The emphasis on velocity in player development

- Advanced analytics that reward consistency and predictability

- The disappearance of veteran mentors to teach the pitch

- Organizations' reluctance to invest development resources in such a specialized skill

"Teams want pitchers who throw 95+ and have predictable outcomes," explained Dickey in a 2020 interview. "The knuckleball is harder to evaluate with modern metrics, so it's seen as riskier."

Yet history suggests the knuckleball will eventually return. The pitch has nearly disappeared several times before, only to resurface when a determined pitcher masters it out of necessity.

A few current prospects are working to keep the tradition alive:

• Steven Wright (RHP), who pitched effectively for Boston from 2013-2019 before injuries and a suspension derailed his career, has worked as a knuckleball instructor.

• Mickey Jannis reached Triple-A with the Orioles organization as a knuckleballer and made his MLB debut at age 33 in 2021.

• Blaine Crim, originally a first baseman in the Rangers system, began experimenting with the knuckleball in 2023 to extend his career.

The pitch's fundamental advantage remains unchanged—it allows pitchers with modest velocity to compete at the highest level, and it creates less arm stress than conventional pitches, potentially extending careers.

Phil Niekro, before his death in 2020, remained optimistic about the knuckleball's future: "As long as there are baseball players who love the game but don't throw hard enough, the knuckleball will survive. It might disappear for a while, but someone will always bring it back."

THE VERDICT: BASEBALL'S UNLIKELY BROTHERHOOD

In a sport increasingly dominated by power—power pitching, power hitting—the knuckleball remains the great equalizer. It allows players with modest physical gifts to compete against the game's elite through craft rather than raw ability. Its practitioners form a small, unique fraternity defined by extraordinary longevity and durability. The combined career numbers of the pitch's modern masters are staggering: over 1,500 wins, an average career length of nearly 20 years, and a combined WAR of over 300.

This success is built on a Zen-like acceptance of imperfection. As Tim Wakefield said, "You have to surrender to it... let physics take over." It's a philosophy that sets them apart from pitchers who strive for precise control. Phil Niekro embraced the chaos: "The beauty of the knuckleball is that I can throw it for 20 years and still not know exactly what it's going to do. Neither does the hitter, the catcher, or the umpire. That's our advantage."

The knuckleball represents baseball at its most democratic—a pitch that doesn't require a 95-mph arm, but rather patience and persistence. It has been the sport's great lifeline. "The knuckleball has saved more careers than Tommy John surgery," joked Wakefield, but there's some truth in his humor. For many, it provided a path to long, successful careers that might otherwise have never happened.

While the pitch may be dormant in today's game, baseball history suggests the knuckleball will return. Someone, somewhere, is likely working on it right now—a pitcher whose fastball isn't quite fast enough, whose breaking balls don't quite break enough, but who refuses to give up on the dream.

And when that pitcher makes it to the majors, baffling hitters with the flutter of a butterfly with hiccups, the great knuckleball tradition will continue—baseball's most unpredictable pitch, thrown by its most unlikely heroes