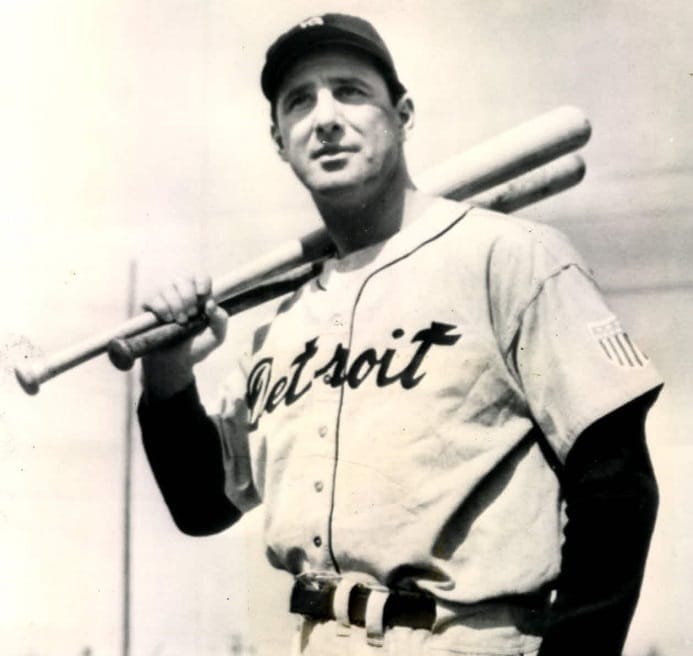

Hank Greenberg: The Slugger Who Gave His Prime to His Country

The Detroit Powerhouse

When Hank Greenberg stepped into the batter's box in 1933, the Detroit Tigers had found something special. Not just a good hitter. Not just a promising young player. They'd found a force of nature who would redefine power hitting in the American League.

His first full season told you everything you needed to know. The 22-year-old first baseman hit .301 with 12 home runs and 87 RBIs. Solid numbers, sure, but just a warmup for what was coming.

The next year, 1934, Greenberg exploded. He slashed .339/.404/.600 with 26 homers and 139 RBIs. His OPS+ of 156 meant he was 56 percent better than the average hitter in the league. He helped drive the Tigers to the pennant and finished sixth in MVP voting. More importantly, he'd arrived as one of baseball's elite sluggers.

Then came 1935. Greenberg put together one of the great seasons in baseball history. He hit .328 with 36 home runs and led the league with 170 RBIs. That RBI total still stands as one of the highest single-season marks ever recorded. His 1.039 OPS and 170 OPS+ were staggering. He won the MVP award and led Detroit to a World Series championship. At 24 years old, Hank Greenberg was already one of the best hitters in baseball.

What made Greenberg so dangerous wasn't just raw power. He had an advanced understanding of the strike zone. His career .412 on-base percentage shows a patient hitter who could work counts and punish mistakes. When pitchers challenged him, he made them pay. When they worked around him, he took his walks. In 1938, he drew 119 free passes while launching 58 home runs.

A Great 1938 Season

That 1938 season deserves its own paragraph. Greenberg chased Babe Ruth's single-season home run record of 60, finishing with 58 homers and 146 RBIs. He posted a .683 slugging percentage and an OPS+ of 169. His isolated power (ISO) that year was a ridiculous .368, showing the pure extra-base hit damage he inflicted. Only two homers short of Ruth's mark, and the what-ifs still linger. Some pitchers wouldn't give him anything to hit down the stretch. Some folks whispered about antisemitism playing a role in how he was pitched to in September. Either way, 58 home runs in 1938 was an otherworldly achievement.

From 1934 through 1940, Greenberg was as good as any hitter in baseball. He posted a .340 average with a .433 on-base percentage and .670 slugging percentage during that seven-year stretch. His 1.103 OPS during those years ranked among the very best in the game. He won two MVP awards and finished in the top three in voting three other times. He accumulated 45.8 WAR during those seven seasons, an average of 6.5 wins above replacement per year.

Call to Duty

But then everything stopped.

Greenberg was drafted into military service in May 1941 after playing just 19 games. He was the first major league star to enter the service, doing so before Pearl Harbor even happened. He was discharged in December 1941, right as the war started, and could have stayed out. Instead, he re-enlisted. He served 47 months total, more than any other major leaguer.

When he came back midway through 1945 at age 34, he'd lost four and a half prime years. The Tigers needed him desperately in their pennant chase. In just 78 games, Greenberg hit .311 with 13 homers and 60 RBIs. More impressively, his .948 OPS and 166 OPS+ showed he still had the elite bat. He hit a grand slam on the final day of the season to clinch the pennant for Detroit. Then he helped them win the World Series.

But the clock was ticking. At 35 in 1946, Greenberg put together one last monster season. He led the American League with 44 home runs and drove in 127 runs. His .604 slugging percentage and 162 OPS+ proved he could still dominate. But his batting average had dropped to .277, and the wear showed. After one more year in Pittsburgh, where he hit 25 homers but struggled to a .249 average, he retired at 36.

The final tally: 331 home runs, 1,276 RBIs, a .313 career average, and a 1.017 OPS across 13 seasons. His 159 OPS+ ranks among the best in history. He accumulated 55.5 career WAR despite missing those years to military service.

How Much Did His Military Service Cost Him in Career Numbers?

Now comes the painful math. What if Greenberg hadn't served?

Look at his age 30 through 33 seasons, the years he missed. Based on his performance before the war and immediately after, conservative projections suggest he would have averaged around 35-40 home runs and 130-140 RBIs per season during those four years. That's another 140-160 home runs right there. Add those to his actual 331, and you're looking at 470-490 career home runs.

But it goes deeper than counting stats. Greenberg's career 6.5 WAR per 162 games suggests those four missing seasons cost him roughly 26 WAR. Add that to his actual 55.5, and he's sitting at over 80 career WAR. That puts him in truly elite company, alongside guys like Willie Mays and Hank Aaron in all-time value.

The 500 home run milestone, which didn't mean what it does now but still mattered, was absolutely within reach. So was 2,000 RBIs, a mark only achieved by legends. His counting stats would have told a different story entirely if not for the war.

And here's the thing that gets lost: Greenberg didn't have to go. After his first discharge in December 1941, he could have stayed home. He re-enlisted by choice. He served his country during its darkest hour, giving up millions of dollars and statistical immortality to do so.

He never complained about it. Never played the "what if" game publicly. When asked about the lost years, he'd shrug and say others sacrificed far more. That was Greenberg. The numbers tell one story. His character tells another.

More Than a Ballplayer

Being Hank Greenberg meant more than hitting baseballs over fences. It meant carrying weight that most players never had to shoulder. It meant representing millions of people who saw themselves in him. It meant standing tall when hatred came at you from the stands and the opposing dugout.

Greenberg was Jewish in an era when antisemitism was casual, accepted, and often vicious. Fans hurled slurs at him. Opposing players tried to get under his skin with insults that would make you sick to hear today. He endured it all while becoming one of baseball's greatest sluggers.

The tension came to a head in September 1934. The Tigers were in a tight pennant race, and two crucial games fell on the Jewish High Holy Days. The first was September 10, Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year. Greenberg agonized over the decision. Should he play? Should he honor the holiday?

He played. He hit two home runs, including the game-winner. The Tigers won. But Greenberg felt conflicted afterward, saying, "I hope I did the right thing. Maybe I shouldn't have played. It's a sacred day."

A week later came Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Jewish calendar, the Day of Atonement. This time Greenberg sat out. He went to synagogue while his teammates played without him. The Tigers lost that game, but they won the pennant anyway.

The Jewish community noticed. Greenberg received letters of support and criticism. Some praised him for playing on Rosh Hashanah and helping his team. Others criticized him for the same reason. The Yom Kippur decision earned widespread respect. A Detroit Free Press headline read "Happy New Year, Hank" after the Rosh Hashanah game. When he sat out Yom Kippur, the Detroit News ran a poem honoring his choice.

Greenberg became a symbol. For Jewish Americans facing discrimination and quotas and casual hatred, he was proof that you could succeed at the highest level. You could be proudly Jewish and proudly American. You didn't have to hide or assimilate completely.

As antisemitism grew worse in Europe, as Hitler rose to power and persecution intensified, Greenberg's role took on deeper meaning. He later wrote, "I came to feel that if I, as a Jew, hit a home run, I was hitting one against Hitler."

That quote captures everything about what Greenberg meant to people. Every home run was defiance. Every success was an answer to the voices saying Jews didn't belong, couldn't compete, should know their place.

The hatred didn't stop. Opponents tried to rattle him with slurs throughout his career. Fans in certain cities made his life miserable. But Greenberg kept hitting. Kept producing. Kept showing up.

Then came May 1947, and a moment that revealed who Hank Greenberg really was.

He was 36 years old, playing first base for the Pittsburgh Pirates in his final season. The Brooklyn Dodgers came to town with their rookie second baseman, Jackie Robinson. Robinson was breaking baseball's color barrier, enduring treatment that made Greenberg's experiences look tame by comparison. The death threats, the spiking, the verbal abuse, all of it designed to break him and drive him out.

During the game, a play at first base resulted in a collision. Robinson barreled into Greenberg, knocking the bigger man down. This was the kind of moment that often sparked fights. A rookie crashing into a veteran star, especially given all the racial tension swirling around Robinson.

Greenberg got up, dusted himself off, and helped Robinson to his feet.

Then he did something more. He offered words of encouragement, telling Robinson he was a good ballplayer and to ignore the name-calling. He told Robinson to stay in there and fight back, to always keep his head up. He said he knew what it was like to be on the receiving end of abuse, having experienced it himself.

Robinson was moved by the gesture. He later told writers that Greenberg had given him encouragement when he needed it most. He called Greenberg "class" and said "class sticks out all over him."

Think about that moment. Two men who'd faced different forms of hatred, separated by years and circumstances, connecting over shared understanding. Greenberg didn't have to say anything. He could have brushed off the collision and moved on. Instead, he used his own painful experiences to lift up someone else fighting the same battle.

The moment mattered. Robinson was isolated that first year, dealing with pressure most people couldn't imagine. Having an established veteran, especially one who understood persecution, offer support meant something real.

Greenberg's support for integration didn't end when his playing career did. After retiring, he became a front office executive. He hired Black players like Larry Doby and Satchel Paige, continuing to push for a game that looked more like America.

His legacy extends beyond statistics. Yes, he was one of the great right-handed power hitters of his era. Yes, his numbers would have been even more impressive without the war. But Greenberg's real impact was showing that you could be yourself, hold onto your identity, and still reach the top.

He didn't hide being Jewish. He didn't pretend the slurs didn't hurt. He didn't minimize what Jackie Robinson faced. He acknowledged the hatred, faced it head-on, and kept going.

When Greenberg was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1956, he became only the second Jewish player to receive that honor. But the numbers and the plaques don't capture what he meant to people. The letters he received from Jewish families. The kids who saw him hit home runs and felt pride in being Jewish. The example he set for treating others with dignity.

Hank Greenberg hit 331 home runs in his career. He drove in 1,276 runs. He won two MVP awards and helped Detroit win championships. Those are facts you can look up in the record books.

But the measure of the man goes beyond box scores. It's found in a moment at first base in Pittsburgh, when an aging slugger helped up a rookie and told him to keep fighting. It's found in the decision to go to synagogue on Yom Kippur despite a pennant race. It's found in the choice to re-enlist and serve his country when he could have stayed home.

The numbers tell you Hank Greenberg was a great ballplayer. The stories tell you he was a great man. Sometimes, if you're lucky, you get both in the same person.