Larry Doby: Breaking Barriers Beyond the Headlines (part 1)

In the narrative of baseball's integration, Jackie Robinson rightfully occupies a central position. Yet just eleven weeks after Robinson broke the National League's color barrier, a 23-year-old former Negro Leagues star named Larry Doby integrated the American League with considerably less fanfare but facing equally daunting challenges. His journey from South Carolina to Cooperstown represents one of baseball's most significant yet underappreciated stories—a testament to quiet dignity, perseverance, and excellence that transformed both a sport and a society.

The Foundation: Negro Leagues Excellence

Larry Doby's baseball journey began long before he stepped onto a Major League diamond, rooted in a Negro Leagues career that demonstrated his exceptional talent.

The Newark Eagles Years

The statistical record reveals Doby's dominance in the Negro National League:

The Teenage Phenomenon:

Doby joined the Newark Eagles in 1942 at just 18 years old, immediately demonstrating advanced skills. He hit .309 with a .796 OPS in his debut season, showing developing power with 3 doubles, 2 triples and a home run in limited action. He demonstrated advanced plate discipline with a .364 OBP and displayed versatility by playing primarily shortstop and second base.

The Pre-War Promise:

His 1943 season showed remarkable development. He improved to a .301 average with a .973 OPS, while his power numbers jumped significantly with 8 doubles, 3 triples and 4 home runs. His plate discipline advanced further with a .419 OBP, and he maintained defensive versatility across multiple positions.

The Military Interruption:

Like many players of his generation, Doby's career was interrupted by military service. He entered the Navy in 1944 after a brief season start and served through 1945 in the Pacific Theater. He was stationed at a segregated base despite the critical war effort and later recalled the irony of fighting for freedom abroad while facing discrimination at home.

The Post-War Explosion:

Returning in 1946, Doby emerged as a superstar. He posted a remarkable .365/.437/.592 slash line and demonstrated elite all-around skills with 12 doubles, 10 triples, and 7 home runs. He was selected to the East-West All-Star Game and helped lead the Newark Eagles to the Negro World Series championship.

The 1947 Dominance:

Before his MLB signing, Doby was demolishing Negro Leagues pitching. He was hitting .354 with a staggering 1.182 OPS and showing tremendous power with 8 home runs in just 30 games. He was on pace for his greatest professional season when the Cleveland Indians purchased his contract. He had fully transitioned to the outfield, where his speed and arm were showcased.

Negro Leagues historian Phil Dixon observed: "Doby's Newark performance established him as one of the elite players in Black baseball. He combined power, speed, and defensive excellence in a way that few others could match. By 1947, he was clearly ready for the biggest stage in baseball."

The Playing Style Evolution

Doby's Negro Leagues development revealed a player whose approach evolved significantly.

The Infield Origins:

He initially developed as a middle infielder, beginning primarily as a shortstop in 1942. He shifted between shortstop and second base in 1943, demonstrating above-average defensive range and hands. He drew comparisons to other Negro Leagues middle infield stars.

The Outfield Transition:

He gradually shifted to the outfield, and by 1946-47, had primarily become an outfielder. He utilized his speed to cover exceptional ground, developed an accurate, powerful throwing arm, and found his defensive home in center field, where his athleticism was maximized.

The Power Development:

His offensive approach evolved substantially. He began as a contact-oriented hitter with developing power, progressively added power to his offensive arsenal, and by 1947, had developed into a legitimate power threat. He maintained high batting average while increasing slugging percentage.

The Complete Player Emergence:

By his final Negro Leagues season, had become a five-tool player. He hit for high average (.354 in partial 1947 season), demonstrated substantial power (8 HR in 30 games), showcased above-average speed on the bases, provided excellent defensive value in center field, and possessed a strong, accurate throwing arm.

Eagles teammate Monte Irvin, who later joined the New York Giants, recalled: "Larry could do everything on a baseball field. He hit for average, hit for power, ran well, fielded his position beautifully, and had a strong arm. There wasn't a weakness in his game. When Cleveland signed him, those of us who had played with him knew they were getting a complete player."

The Newark Community Connection

Beyond statistics, Doby's Negro Leagues experience created deep community connections.

The Local Hero Status:

Born in Camden, South Carolina, Doby moved to Paterson, New Jersey in 1938 at age 14 to join his mother. He attended Eastside High School in Paterson, becoming a multi-sport star. Though he lived in Paterson, he represented local pride in the Newark Eagles' success, creating strong fan connection as a hometown hero throughout the region.

The Mentorship Benefit:

He benefited from guidance of Negro Leagues veterans. He learned from Eagles manager Biz Mackey, a legendary catcher, and received guidance from teammates like Willie Wells and Mule Suttles. He developed both baseball skills and professional approach, and later credited this mentorship with preparing him for MLB challenges.

The Cultural Significance:

The Eagles represented more than just baseball. The team was central to Newark's Black community identity, games became social and cultural events beyond sport, and players served as role models and community representatives. This created foundation for Doby's understanding of his broader responsibility.

Negro Leagues historian Leslie Heaphy noted: "The Newark Eagles weren't just a baseball team—they were a cultural institution in the Black community. Doby's development there wasn't just about baseball skills, but about understanding his place in a larger social context. This preparation would prove invaluable when he faced the challenges of integration."

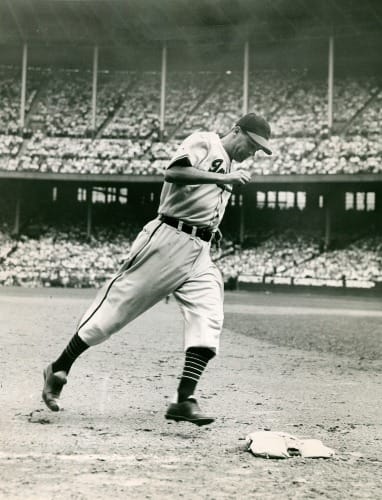

The Pioneer: American League Integration

On July 5, 1947, Larry Doby became the American League's first Black player when he pinch-hit for the Cleveland Indians against the Chicago White Sox. While this moment came after Jackie Robinson's National League debut, Doby's integration journey involved unique challenges and circumstances.

The Hasty Transition

Unlike Robinson's carefully planned integration, Doby's transition to MLB was abrupt.

The Sudden Signing:

Cleveland owner Bill Veeck moved quickly and with minimal preparation. He purchased Doby's contract directly from Newark Eagles on July 3 through an agreement involving an initial payment of $10,000 to the Eagles, plus an additional $5,000 bonus paid to the Eagles' owners, Effa and Abe Manley, when Doby remained with the Indians for at least 30 days. Veeck gave Doby just two days' notice before his debut, provided no minor league transition period, and created situation where Doby had minimal time to prepare mentally or physically.

The Position Challenge:

Doby faced a difficult baseball transition. He had primarily played infield in Negro Leagues but was signed as an outfielder, required to learn a new position at the Major League level. He initially struggled with the defensive adjustment and had no opportunity to develop outfield skills before his debut.

The Mid-Season Pressure:

He entered MLB during an active pennant race. He joined Cleveland team in championship contention, faced immediate expectation to contribute to winning team, had no spring training period to adjust to teammates and environment, and was thrust immediately into high-leverage situations.

The Limited Playing Time:

His initial MLB experience came in sporadic opportunities. He appeared in just 29 games in 1947, received only 32 at-bats in his debut season, was often used only as a pinch-hitter rather than starter, and had difficulty establishing rhythm with inconsistent playing time.

Doby later reflected on this challenge: "I can't tell you how tough it was to sit on that bench and not play. In the Negro Leagues, I played every day. Suddenly I'm sitting, watching, trying to learn a new position, and expected to be ready when called upon. It was the hardest thing I'd experienced in baseball."

The Social Challenges

Doby confronted racial barriers that, while similar to Robinson's experience, had distinct elements.

The Teammate Reception:

The initial Cleveland clubhouse was notably cold. Several players refused to shake Doby's hand on his first day, he experienced isolation in clubhouse and on team bus, found few allies among teammates initially, and faced silent treatment from many players.

The Regional Factor:

The American League's geographical footprint created unique challenges. AL teams were primarily in northern cities but maintained southern attitudes. Detroit, Boston, and Chicago presented particularly difficult environments, creating less progressive climate than some NL cities. This created environment where Doby often felt completely isolated.

The Second Pioneer Paradox:

Being second brought distinct challenges. He received far less media attention and support than Robinson, had no equivalent to Branch Rickey designing an integration plan, lacked the extensive preparation Robinson received, and experienced similar abuse but with less public sympathy or awareness.

The Housing Discrimination:

He faced practical challenges of segregation. He was often unable to stay with team at hotels, required to find separate accommodations in many cities, and frequently separated from teammates during road trips. This created logistical complications beyond the emotional toll.

Indians teammate Joe Gordon, one of the few players who immediately welcomed Doby, recalled: "The way Larry was treated by some of the guys on our team and around the league was shameful. He never complained, never made excuses, just showed up and did his job under circumstances most of us couldn't imagine."

The Verbal and Physical Abuse

Like Robinson, Doby endured sustained hostility that tested his resolve.

The On-Field Targeting:

He became target for opposing players. He experienced deliberate spiking attempts when covering bases, faced pitchers who explicitly threw at him, endured verbal abuse from opposing dugouts, and confronted fielders who would apply unnecessarily hard tags.

The Crowd Hostility:

Certain AL cities were particularly challenging. Detroit's fans were notorious for racial abuse, Boston's Fenway Park created hostile environment, and even some Cleveland fans were initially unwelcoming. This created atmosphere where he played under constant verbal assault.

The Threat Environment:

He faced explicit threats to his safety. He received death threats in multiple American League cities, required occasional security protection, experienced anxiety about family safety, and played under constant concern about physical harm.

The Isolation Factor:

Unlike Robinson, he often faced these challenges with less support. He had no equivalent to PeeWee Reese's public support among teammates, received less media coverage highlighting his challenges, had fewer allied organizations providing encouragement, and this created situation where he frequently felt completely alone.

Doby described this isolation years later: "I couldn't react to prejudicial situations. I couldn't fight back. Jackie had Mr. Rickey to go to; I had no one. I was alone. If I had shown any aggression, they would have said, 'See, we told you so. They're not ready.' So I had to take it and pretend it didn't hurt."

The Response Strategy

Doby developed a distinctive approach to handling these challenges.

The Dignified Restraint:

He maintained remarkable composure. He never publicly retaliated against abuse, channeled frustration into performance, maintained professional demeanor despite provocation, and allowed his play rather than words to respond to critics.

The Performance Focus:

He concentrated intensely on baseball fundamentals. He used preparation and practice as psychological escape, developed reputation for meticulous pre-game routine, channeled emotional energy into skill development, and created excellence as his primary response to adversity.

The Selective Trust:

He carefully built relationships with supportive figures. He formed strong bond with Bill Veeck, who consistently supported him, developed friendship with Indians teammate Joe Gordon, maintained connection with Negro Leagues friends, and created small but vital support network.

The Private Processing:

He developed methods to manage the psychological burden. He wrote private journals documenting his experiences, maintained close contact with family for emotional support, developed compartmentalization techniques to separate baseball from abuse, and created psychological strategies that preserved his mental health.

Indians owner Bill Veeck observed Doby's approach: "Larry absorbed everything—every insult, every slight, every injustice—and converted it into determination. He never let them see him flinch, never gave them the satisfaction. His dignity under the most degrading circumstances was a kind of quiet heroism that most people can't comprehend."

The Star: Major League Excellence

Despite the immense challenges of integration, Doby quickly emerged as one of baseball's premier players, demonstrating that his Negro Leagues excellence translated completely to the Major League level.

The Statistical Dominance

After his limited 1947 opportunity, Doby's numbers reveal a legitimate superstar.

The Immediate Impact:

His first full season in 1948 showed his true ability. He hit .301/.384/.490 in 121 games, contributed 14 home runs and 66 RBIs, scored 83 runs while showing excellent plate discipline, and helped Cleveland win the 1948 World Series, their last championship.

The Peak Performance:

From 1949-1955, Doby established himself among baseball's elite. He made seven consecutive All-Star teams (1949-1955), twice led the American League in home runs (1952 with 32, and 1954 with 32), led the AL in RBIs in 1954 with 126, and finished second in MVP voting in 1954.

The Advanced Metrics Validation:

Modern analytics confirm his greatness. He accumulated 43.1 WAR in his 10 seasons with Cleveland, posted five seasons of 5+ WAR (elite performance level), produced a career OPS+ of 140 including his Negro Leagues performance (40% better than league average), and ranks among the most valuable outfielders of his era by any measure.

The Consistency Factor:

He maintained excellence over an extended period. He hit 20+ home runs for eight consecutive seasons (1949-1956), posted .380+ OBP in four consecutive seasons (1949-1952), and drove in 75+ runs in seven different seasons. He established himself as one of the most consistent performers in baseball.

Baseball historian Bill James assessed Doby's statistical case: "When you look at the numbers objectively, Doby was clearly one of the premier players of his era. For the period 1949-1956, he ranks among the top five outfielders in baseball by nearly any meaningful measure. His combination of power, on-base ability, and defensive value made him a genuinely elite player."

The Complete Player Profile

Beyond raw statistics, Doby exhibited a multi-dimensional game that made him exceptionally valuable.

The Power-Speed Combination:

He demonstrated rare athletic versatility. He hit 253 AL home runs while stealing 47 bases, used speed to take extra bases and cover defensive ground, ranked among league leaders in triples despite playing in pitcher-friendly Cleveland Stadium, and created offensive value through multiple channels.

The Defensive Excellence:

He developed into an elite center fielder. He covered exceptional ground in spacious Cleveland Stadium, possessed strong, accurate throwing arm, developed reputation for spectacular catches, and provided significant value through defense despite limited metrics of the era.

The Plate Discipline:

He displayed advanced approach at the plate. His career .389 OBP came despite playing in pitcher-friendly era. He drew 871 walks in his AL career, maintained high OBP even during average fluctuations, and demonstrated patience that was ahead of his time.

The Situational Excellence:

He developed reputation for clutch performance. He hit .318 in the 1948 World Series, maintained high performance in pennant races, produced .856 OPS in high-leverage situations, and earned teammates' trust in crucial moments.

Cleveland teammate Bob Feller, a Hall of Fame pitcher who initially gave Doby a cold reception but later became supportive, acknowledged: "Larry was as complete a player as you could find. He could hit for average, hit for power, run, field, and throw. Once he got comfortable in the outfield, there wasn't anything on a baseball field he couldn't do well. He was truly a five-tool player before anyone used that term."

The Team Impact

Doby's excellence translated directly to team success.

The Championship Contribution:

He played crucial role in Cleveland's success. He was a key contributor to 1948 World Series championship team and became the first Black player to homer in a World Series game when he connected on October 9, 1948. He helped Cleveland set AL record with 111 wins in 1954 and participated in two World Series (1948, 1954).

The Lineup Cornerstone:

He became offensive centerpiece of Indians teams. He served as cleanup hitter during most productive years, provided protection for other hitters in lineup, consistently produced despite limited support in some Cleveland lineups, and created offensive foundation that maximized pitching staff's excellence.

The Leadership Evolution:

He gradually assumed team leadership role. His initially quiet presence evolved into respected voice, he became player others looked to in crucial situations, developed into mentor for younger players, and earned respect through performance and character despite initial rejection.

The Franchise Value:

He provided exceptional return on Cleveland's investment. The agreement with Newark Eagles cost Cleveland $10,000 initially plus a $5,000 bonus, totaling $15,000. He delivered 43.1 WAR over 10 Cleveland seasons, helped generate attendance increases as fans embraced him, and represented one of baseball's greatest value acquisitions.

Cleveland teammate Al Rosen noted: "Larry became the heart of our team. Initially, some guys didn't want him there, but his ability and character eventually won everyone over. By the early 1950s, he was our most important player, the guy we couldn't afford to lose. When we needed a big hit, we wanted Larry at the plate."