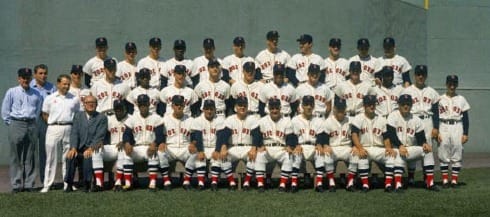

Rebirth in Boston: How the "Impossible Dream" Changed the Red Sox Forever

The 1967 Boston Red Sox didn't just win a pennant. They resurrected a franchise.

Before the "Impossible Dream" season, the Red Sox were a baseball afterthought – a once-proud organization mired in mediocrity, playing before sparse crowds in an aging ballpark. After 1967, they became "Red Sox Nation" – one of baseball's most passionate fan bases, with Fenway Park as their cathedral and a regional identity built around their beloved team.

The transformation wasn't just about wins and losses. It was a cultural sea change that altered the franchise's DNA and rewrote the relationship between a team and its city. Let's examine how the 1967 miracle changed the Red Sox -- and Boston -- forever.

The Pre-1967 Wasteland: A Franchise in Decline

To understand the impact of 1967, we need to appreciate just how far the Red Sox had fallen before their resurrection.

The numbers tell a bleak story:

- Eight consecutive losing seasons (1959-1966)

- Ninth-place finish in 1966 (10-team league)

- Attendance under 10,000 per game in 1966

- No pennant since 1946

- No World Series championship since 1918

Beyond the statistics, the franchise had developed a reputation for underachievement and racial tension. The Red Sox were the last major league team to integrate, not signing their first Black player (Pumpsie Green) until 1959 -- 12 years after Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier.

"Before 1967, going to Fenway was like visiting a mausoleum," longtime Boston sportswriter Ray Fitzgerald wrote. "The place was half-empty, and the fans who did show up seemed to be there out of habit rather than hope."

Former Boston Mayor John Collins captured the prevailing sentiment: "By 1966, there was serious talk about moving the team. The ballpark was considered antiquated, attendance was terrible, and the team had been irrelevant for nearly a decade."

The New Regime: Williams Takes Charge

The first hint of change came in October 1966, when the Red Sox hired Dick Williams as manager. Williams, just 38 years old, had no major league managerial experience but had led Toronto to an International League championship.

What Williams lacked in experience, he made up for in confidence and discipline. On his first day, he boldly declared, "We'll win more than we lose" -- a statement that seemed laughable given the team's recent history.

Williams immediately set a new tone. Players who reported to 1967 spring training out of shape were fined. Curfews were strictly enforced. The country club atmosphere that had permeated the team was gone.

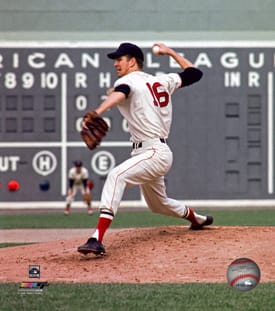

"Dick Williams changed everything," pitcher Jim Lonborg (RHP, BOS) recalled. "From day one, he made it clear that the old way of doing things was over. We were going to play fundamental baseball, we were going to be prepared, and we were going to expect to win."

The players didn't all love Williams -- many found him abrasive and dictatorial -- but they respected him. More importantly, they responded to his methods.

The Season That Changed Everything

When the Red Sox won on Opening Day in 1967, few took notice. When they remained competitive through May, it was considered a fluke. When they were still in the race at the All-Star break, people started paying attention.

By August, Fenway Park was regularly selling out. By September, Red Sox fever had gripped New England. The daily drama of the four-team pennant race captured the imagination of a region that had long since given up on baseball success.

Three moments stand out as turning points in transforming the franchise:

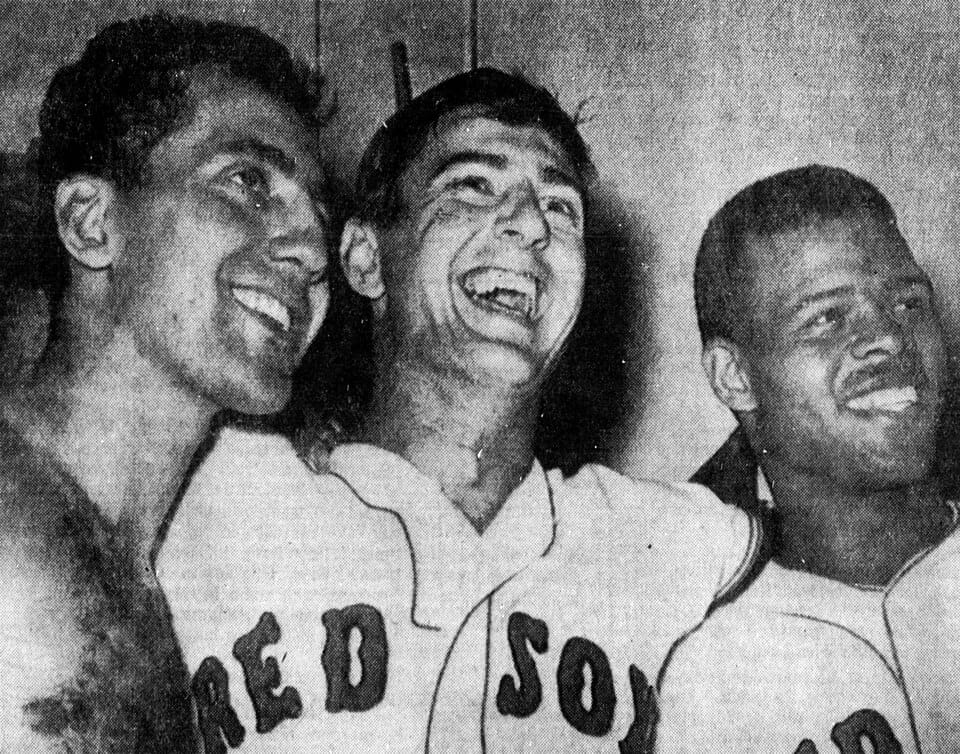

- The Tony Conigliaro Beaning (August 18): When young star Tony Conigliaro (OF, BOS) was struck in the face by a Jack Hamilton (RHP, CAL) fastball and his season was ended, it could have derailed the team. Instead, it galvanized the team and the city. "After Tony C. got hit, something changed," teammate Rico Petrocelli (SS, BOS) said. "We were no longer just playing for ourselves. We were playing for Tony, for the fans, for the city. It became bigger than baseball."

- The Final Weekend Showdown (September 30 - October 1): The entire season came down to the final two games against the Minnesota Twins, who were tied with Boston for first place. On Saturday, September 30, José Santiago pitched the Red Sox to a gritty 6-4 victory, setting the stage for a winner-take-all finale. "That game changed the relationship between the team and the city," Boston Globe columnist Will McDonough wrote. "Suddenly, it wasn't just a baseball team. It was Boston's team."

- The Pennant Clincher (October 1): With the American League pennant on the line, Jim Lonborg—pitching on just two days' rest—took the mound and delivered a complete-game masterpiece. The Red Sox defeated the Twins 5-3, and the emotional release was unlike anything Boston had experienced in decades. Fans stormed the field, players were carried off on shoulders, and a city celebrated as one. "I've never seen so many grown men cry," Red Sox broadcaster Ken Coleman said of the scene at Fenway that day. "These weren't just baseball fans. They were people who had their faith rewarded after years of disappointment."

IV. The Enduring Legacy: How 1967 Forged a New Identity

The impact of the 1967 season went far beyond a single pennant. It fundamentally reshaped the franchise's finances, its cultural standing, and its very identity for generations to come.

The Numbers: Quantifying the Impact

The statistical impact of the 1967 season on the Red Sox franchise is staggering:

Attendance:

- 1966: 811,172 (8,514 per game)

- 1967: 1,727,832 (21,331 per game)

- Increase: 113%

This remains one of the largest year-to-year attendance jumps in baseball history.

Television Ratings:

- Local TV ratings for Red Sox games increased by approximately 300% from 1966 to 1967

- The team negotiated a new broadcast deal after 1967 that tripled their television revenue

Franchise Value:

- Estimated value in 1966: $10 million

- Estimated value in 1968: $18 million

- Increase: 80%

Season Ticket Sales:

- 1967: Approximately 2,000

- 1968: Over 10,000 (sold out in January)

Beyond these numbers, the entire economic ecosystem around the Red Sox transformed. Souvenir sales exploded. Businesses near Fenway Park thrived. The team added staff in every department from marketing to ticket sales to media relations.

"The 1967 season didn't just save the Red Sox," baseball economist Andrew Zimbalist later wrote. "It created the modern Red Sox business enterprise."

The Cultural Shift: Birth of Red Sox Nation

Perhaps the most significant impact of 1967 was the cultural transformation it triggered. The term "Red Sox Nation" wasn't coined until the 1970s, but its foundations were laid during the Impossible Dream season.

Several key shifts occurred:

- Regional Identity: The Red Sox became synonymous with New England identity. From Maine to Connecticut, following the Red Sox became a cultural touchstone that united the region. "Before '67, the Red Sox were Boston's team," New England historian Doris Kearns Goodwin wrote. "After '67, they belonged to all of New England."

- Fenway Park's Salvation: Prior to 1967, Fenway Park was considered obsolete. Plans were being discussed for a new stadium, possibly as part of a domed facility in the South Boston area. After 1967, Fenway became sacred ground. The quirky old ballpark with its unique features -- the Green Monster, Pesky's Pole, the manual scoreboard -- became beloved rather than outdated. "The '67 season saved Fenway Park," former Red Sox CEO John Harrington acknowledged years later. "Without that pennant race, we probably would have built a new stadium in the 1970s."

- Generational Connection: The 1967 season created a new generation of Red Sox fans. Children who experienced the pennant race with their parents became lifelong devotees, creating a multigenerational fan base that persists today. "So many fans trace their Red Sox fandom to 1967," team historian Dick Bresciani noted. "I can't tell you how many people have told me, 'My dad took me to Fenway during the '67 season, and I've been hooked ever since.'"

- Media Coverage Explosion: Prior to 1967, the Red Sox received modest coverage in local newspapers and broadcast outlets. After the pennant race, Red Sox coverage became a media industry unto itself. The Boston Globe expanded its Red Sox coverage from one reporter to three. Local television stations began dedicating entire segments to the team. Radio stations fought for broadcasting rights. "After '67, covering the Red Sox wasn't just a beat, it was a career path," longtime Boston sportswriter Peter Gammons said. "The appetite for Red Sox news became insatiable."

The Team's New Identity: From Underachievers to Contenders

Perhaps the most profound change came in how the team viewed itself. Before 1967, the Red Sox were known for squandering talent and finding ways to lose. After the Impossible Dream, they developed a new organizational identity centered on competitiveness and excellence.

From 1967 through 1979, the Red Sox:

- Finished below .500 only once

- Won 90+ games five times

- Captured another pennant in 1975

- Developed multiple Hall of Fame players (Carl Yastrzemski, Jim Rice, Carlton Fisk)

"The '67 season changed our expectations," Red Sox general manager Dick O'Connell said in 1977. "Before that year, we hoped to be competitive. After it, we expected to contend for championships."

This shift in mentality extended throughout the organization. The Red Sox became more aggressive in player development, international scouting, and free agent pursuits. They embraced new training methods and analytical approaches.

"The Impossible Dream season gave the organization confidence," Jim Rice later recalled. "When I came up in the early '70s, there was none of that 'we can't win' attitude. The expectation was that the Red Sox should be in the race every year."

The Dark Side: The Burden of Expectations

The 1967 season's impact wasn't entirely positive. It also created expectations that would haunt the franchise for decades.

Having tasted success, Red Sox fans now demanded it regularly. The painful near-misses that followed -- particularly the 1975 and 1986 World Series losses -- were made more agonizing by the heightened expectations that 1967 had created.

"The '67 team showed us what was possible," Boston columnist Dan Shaughnessy wrote. "But it also made every subsequent failure more painful. It's the curse of high expectations."

Some players who followed the 1967 team felt burdened by the comparisons. "We were always being measured against the Impossible Dream team," outfielder Dwight Evans said years later. "No matter what we accomplished, people would say, 'Yeah, but can they capture the magic of '67?'"

The Impossible Dream Team as Cultural Touchstone

The 1967 Red Sox took on a mythic quality in Boston culture. For decades afterward, members of that team received standing ovations whenever they returned to Fenway Park.

"Those guys will never have to buy a drink in Boston," longtime Red Sox fan and author Stephen King once noted. "They didn't just win games; they restored a city's faith."

Novelist John Updike, who had previously written about Ted Williams' final game in his famous "Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu" essay, observed: "The '67 Red Sox accomplished something rare in sports – they transcended the game itself to become a symbol of possibility."

Individual Legacies Transformed

For several key figures, the 1967 season fundamentally altered their legacy in baseball and Boston history:

Carl Yastrzemski (OF, BOS): Before 1967, Yaz was considered a good player who had the impossible task of replacing Ted Williams. After his Triple Crown season and September heroics, he became a Boston icon. His number 8 was retired, a statue was erected outside Fenway, and he remains perhaps the most beloved living Red Sox player. His 1967 season was incredible, as he hit .326 with 44 home runs and 121 RBIs. How great was his September? In 96 at bats, he was recorded 40 hits, nine home runs, 26 RBIs, with a slash line of .417/.504/.760 and a 1.265 OPS! Those are the numbers of a MVP, future Hall of Famer and legend, which is exactly what he became after that performance. Through the course of baseball history, we have heard stories about players putting their team on their back. This may be one of the best examples of that figure of speech. "The '67 season changed everything for me," Yastrzemski admitted years later. "Before that year, I was just another player. After it, I couldn't go anywhere in New England without being recognized."

Jim Lonborg (RHP, BOS): His Cy Young-winning performance in 1967 (22 wins, 3.16 ERA, 246 strikeouts) ensured Lonborg's place in Red Sox lore, even though injuries prevented him from reaching the same heights again. After retiring, he established a successful dental practice in the Boston area, where patients still regularly asked about the Impossible Dream season decades later.

Dick Williams: His success in 1967 launched a Hall of Fame managerial career that included pennants with three different franchises (Red Sox, Oakland Athletics, San Diego Padres). Williams was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2008, with his 1967 season prominently mentioned in his plaque.

Tom Yawkey: The longtime Red Sox owner had been criticized for years of mismanagement. The 1967 season temporarily rehabilitated his image, though later revelations about the team's racial history during his ownership have complicated his legacy.

The Economic Ripple Effect: Transforming a Neighborhood and City

The 1967 season's impact extended beyond the Red Sox organization to transform the economy of the Fenway neighborhood and contribute to Boston's revitalization.

"Before '67, the Fenway area was declining," urban planner Kevin Lynch wrote in a 1970 study. "After the pennant race, investment returned to the neighborhood. Property values increased, new businesses opened, and the area developed a distinct identity centered around the ballpark."

"The '67 Red Sox made people feel good about Boston again," former mayor Kevin White said years later. "That positive energy contributed to the city's comeback story."

The Sporting Legacy: Changing How Teams Connect with Fans

The 1967 Red Sox created a template for how sports franchises could build deep connections with their communities. Their success story – a young team exceeding expectations, playing an exciting brand of baseball, led by homegrown stars – became a model that other organizations sought to emulate.

"After seeing what happened in Boston in '67, every struggling franchise wanted to capture that same magic," sports marketing pioneer Mark McCormack observed. "They showed how a team could become woven into the fabric of a region's identity."

Specific innovations that became industry standards included:

- Expanded Media Access: The 1967 Red Sox were unusually accessible to reporters, creating personal connections between players and fans through media coverage.

- Community Outreach: Following the pennant race, the Red Sox significantly expanded their community programs, with players making hundreds of appearances throughout New England.

- Embracing History: The team began more actively celebrating its history and traditions, recognizing that nostalgia created powerful bonds with fans.

- Regional Marketing: Rather than focusing solely on Boston, the team actively cultivated its fan base throughout New England with targeted marketing campaigns.

These approaches have become standard practice in sports business, but the 1967 Red Sox were among the pioneers.

The Legacy of Belief: "Why Not Us?"

Perhaps the most enduring impact of the 1967 season was psychological. It created a powerful narrative of possibility that would sustain Red Sox fans through decades of near-misses until the 2004 championship.

When the Red Sox finally broke their 86-year championship drought in 2004, many players from the 1967 team were invited to participate in the celebrations. Carl Yastrzemski threw out the first pitch of the World Series, symbolically connecting the team that started the modern Red Sox era with the one that fulfilled its ultimate promise.

"In many ways, 2004 completed what 1967 started," team president Larry Lucchino said during the championship celebration. "The Impossible Dream showed what was possible. The 2004 team made it reality."

The Impossible Dream: Still Resonating

More than five decades later, the 1967 Red Sox continue to hold a special place in baseball lore and New England culture. Books, documentaries, and oral histories continue to be produced about the season. Memorabilia from that team commands premium prices at auctions. The surviving players remain revered figures throughout the region.

When Fenway Park underwent major renovations in the early 2000s, the Red Sox ownership was careful to preserve the essential character of the ballpark that had been saved by the 1967 team. The manual scoreboard, the Green Monster, and other features that might have been considered obsolete were instead celebrated as connections to that magical season.

Baseball historian Glenn Stout perhaps best summarized the 1967 season's enduring legacy: "Some teams win championships and are eventually forgotten. The '67 Red Sox lost the World Series, yet they're remembered more vividly than many champions. That's because they didn't just win games -- they changed what a baseball team could mean to a city and a region."

Former Red Sox pitcher Luis Tiant, who joined the team in the 1970s, observed: "When I came to Boston, I quickly learned there were two kinds of Red Sox history – before 1967 and after 1967. Everything changed with that team."

The "Impossible Dream" nickname itself has become a permanent part of baseball vernacular -- shorthand for any underdog team that exceeds expectations and captures public imagination.

For the Red Sox franchise, the 1967 season wasn't just a fleeting moment of success. It was a rebirth that transformed a struggling baseball team into one of sports' most iconic institutions. The pennant they won that October was just the beginning of a much larger story – one that continues to unfold at Fenway Park to this day.