The Great 1954 Season

Three terrific storylines from the 1954 season

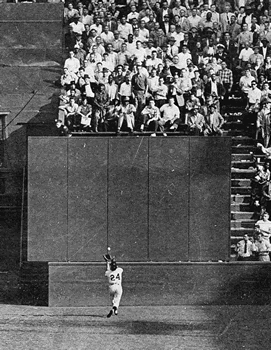

The Catch That Defined a Series

The Polo Grounds stood silent for just a moment. Then 52,751 fans erupted.

Willie Mays (OF, NYG) had just made the most famous catch in World Series history. But on September 29, 1954, it was just another play for the 23-year-old center fielder who'd spent most of the previous two years in the Army.

The Cleveland Indians came into the Fall Classic as heavy favorites. They'd won 111 games during the regular season, an American League record at the time. The New York Giants? They were 8-5 underdogs despite winning 97 games and the National League pennant.

Game One looked like it might go Cleveland's way early. Vic Wertz (1B/OF, CLE) drove in two runs in the first inning off Sal Maglie, giving the Indians a 2-0 lead. The Giants tied it in the third when Whitey Lockman and Al Dark singled, followed by Don Mueller's force out and Hank Thompson's RBI single.

Then came the eighth inning.

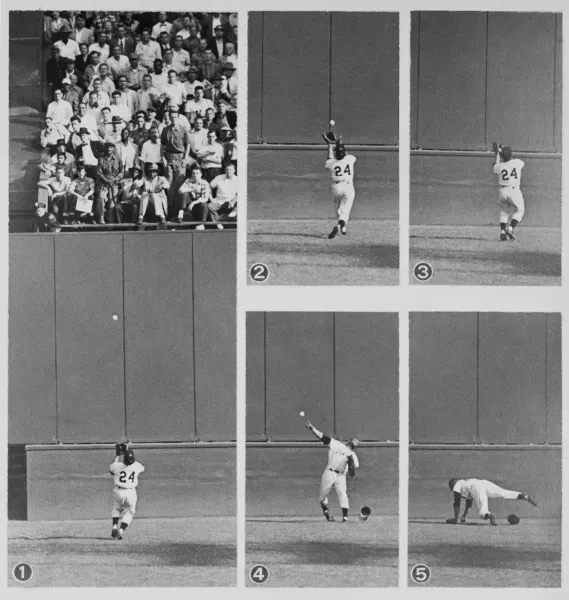

Maglie was done. Manager Leo Durocher brought in lefty Don Liddle to face the left-handed-hitting Wertz, who already had three hits in the game. Two runners were on base. No outs. Wertz crushed Liddle's fourth pitch deep into the cavernous center field of the Polo Grounds.

Mays turned his back to home plate and ran. He didn't track the ball over his shoulder. He just ran toward the wall, 460 feet from home plate. The ball was sailing over his head when Mays reached up, caught it, and spun around to fire the ball back to the infield. Larry Doby (OF, CLE) tagged from second and made it to third, but the rally died there.

"I had it all the way," Mays said after the game. "There was nothing too hard about it."

That undersold what everyone had just witnessed. Durocher, standing in the dugout, had turned around and said, "Oh no," before watching Mays run the ball down.

The game stayed tied through nine innings. Marv Grissom (OF, CLE), who replaced Liddle after the catch, became the forgotten hero. He pitched 3.1 innings of scoreless relief, stranding seven Cleveland runners in the final three frames. In the 10th inning, he walked the bases loaded but struck out Dave Pope and got Jim Hegan to fly out.

Bob Lemon (RHP, CLE) had allowed just four hits from the fourth through ninth innings. He'd settled down after that shaky third. But in the bottom of the 10th, he walked Mays and intentionally walked Hank Thompson (3B, NYG) after Mays stole second.

Dusty Rhodes pinch-hit for Monte Irvin. He swung at Lemon's first pitch and hit a pop fly down the right-field line. Indians manager Al Lopez thought it would drift foul. Instead, it barely cleared the short right-field wall, 270 feet from home plate. The three-run homer gave the Giants a 5-2 victory.

"We were beaten by the longest out and the shortest home run of the year," Lopez said afterward.

Mays finished 1954 with a .345 batting average, 41 home runs, and a National League-leading .667 slugging percentage. His 10.4 WAR paced the circuit. He won the MVP award. But that catch, made with runners on base in a tie game during the World Series, became the signature moment of his career.

The Giants swept Cleveland in four games. Mays' catch in Game One set the tone for everything that followed.

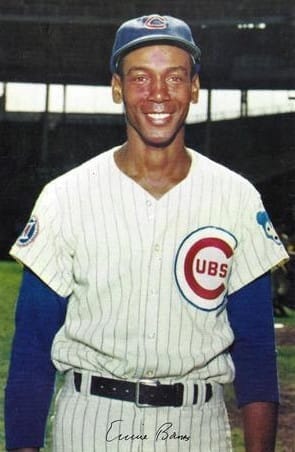

Mr. Cub's First Full Season

Ernie Banks (SS, CHC) played just 10 games for the Chicago Cubs in 1953. He debuted on September 17, becoming the Cubs' first Black player alongside Gene Baker, who joined the roster shortly after. The Cubs were one of the slower National League teams to integrate, waiting six years after Jackie Robinson broke baseball's color barrier.

In 1954, Banks got his first full season. He made it count.

The 23-year-old shortstop appeared in 154 games and posted a .275/.326/.427 slash line with 19 home runs and 79 RBIs. His 2.5 WAR ranked second among Cubs position players behind only Hank Sauer.

Banks hit for average and power from the shortstop position, a rare combination in 1954. His 94 OPS+ might seem modest, but it was solid production from a premium defensive position. He showed gap power with 19 doubles and seven triples to go with his 19 homers. The 253 total bases ranked fourth on the team.

The Cubs finished 64-90 that season, seventh in the eight-team National League. They scored 702 runs and allowed 828. Banks provided one of the few bright spots on a roster desperately searching for talent.

He finished 16th in MVP voting and second in Rookie of the Year balloting behind Wally Moon of the St. Louis Cardinals. Moon hit .304 with a 128 OPS+, but Banks' power numbers from shortstop impressed voters. Gene Conley, the dual-sport athlete who also played for the NBA's Boston Celtics, finished third in ROY voting as a pitcher for the Milwaukee Braves.

Banks' defensive metrics from 1954 are less reliable than modern statistics, but he handled 593 chances at shortstop and turned 105 double plays. He committed 34 errors, a high number that would improve as he gained experience at the major league level.

What stands out most about Banks' first full season is his durability. He played 154 of 154 games. He batted 593 times. For a young player adjusting to integrated baseball in Chicago, that workload showed remarkable consistency and toughness.

The Cubs signed Banks and Baker from the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro Leagues. Baker actually signed first but was sent to the minors before joining Banks on the big-league roster. The two became Chicago's integration pioneers, though the team moved slowly compared to other National League clubs. By 1954, only the Cardinals and Phillies had yet to field a Black player in the senior circuit.

Banks would spend his entire 19-year career in Chicago. He'd win back-to-back MVP awards in 1958 and 1959, hitting 47 homers each season. He'd smash 512 career home runs and make 14 All-Star teams. He'd earn the nickname "Mr. Cub" and become one of the most beloved players in franchise history.

But it started in 1954. A 23-year-old shortstop playing every game for a seventh-place team, showing Cubs fans what excellence looked like at the game's toughest defensive position.

Milwaukee's Quiet Superstar

Milwaukee went baseball-crazy in 1954. The Braves had moved from Boston before the 1953 season, and the city embraced its new team with open arms. County Stadium drew over 2.1 million fans in 1954, shattering attendance records across baseball.

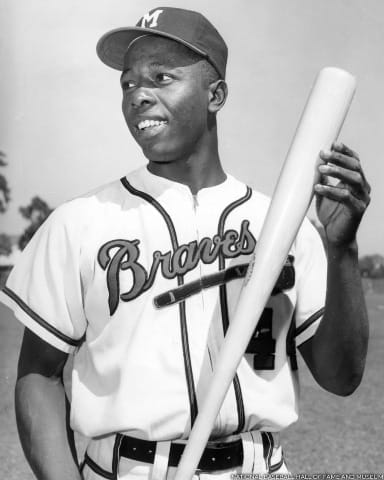

Fans packed the new ballpark to watch Warren Spahn (LHP, MIL) pitch and Eddie Mathews (3B, MIL) launch home runs. They cheered for Joe Adcock and Del Crandall. But a quiet 20-year-old right fielder named Henry Aaron (OF, MIL) put together a rookie season that got overlooked in all the excitement.

Aaron hit .280/.322/.447 in 122 games. He smashed 13 home runs, drove in 69 runs, and collected 27 doubles. His 1.5 WAR ranked sixth among Braves position players. Nothing spectacular. Nothing that screamed future Hall of Famer.

But look closer at those numbers. Aaron posted a 104 OPS+, meaning he hit 4 percent better than league average as a 20-year-old rookie. His .447 slugging percentage showed gap power that would develop into home-run power as he matured. He struck out just 39 times in 468 at-bats, exceptional plate discipline for such a young player.

The Braves finished 89-65, third place in the National League. They scored 710 runs, fourth-best in the league. Mathews led the way with 40 homers, 103 RBIs, and a ridiculous 172 OPS+. Adcock added 23 homers. The pitching staff, anchored by Spahn's 21 wins, posted a 3.58 ERA.

Milwaukee loved its new team. County Stadium sat on the city's west side, a modern ballpark that replaced the aging minor-league parks that had hosted Milwaukee baseball for decades. Fans arrived early and stayed late. They bought tickets in bunches. Baseball had returned to Milwaukee after a 52-year absence, and the city wasn't taking it for granted.

Aaron finished fourth in Rookie of the Year voting behind Wally Moon, Ernie Banks, and Gene Conley. Moon won easily, hitting .304 for St. Louis with a .371 on-base percentage. Aaron's numbers didn't jump off the page the way Moon's did.

What the voters missed was Aaron's age and his projection. He was 20 years old playing right field in the major leagues. He made solid contact. He showed doubles power. He drove in runs. Most rookies that young struggle to make consistent contact. Aaron looked comfortable from day one.

Bill Bruton played center field and led the National League with 34 stolen bases. Bobby Thomson, who'd hit the "Shot Heard 'Round the World" for the Giants in 1951, played left field for 43 games before injuries ended his season. Aaron held down right field and showed enough that the Braves knew they had something special developing.

Milwaukee's fans celebrated their winning team. They watched Spahn work his magic on the mound. They saw Mathews crush moonshots. They witnessed Adcock drive the ball to all fields. And quietly, almost without notice, they watched a 20-year-old rookie named Henry Aaron begin a career that would lead to 755 home runs and a place among baseball's all-time greats.

The excitement in Milwaukee was real. The attendance records were real. The pennant chase was real. And tucked into that rookie season was the beginning of one of the greatest careers in baseball history.