The Greatest Second Baseman Ever: Rogers Hornsby and His Unmatched Legacy (Part 1)

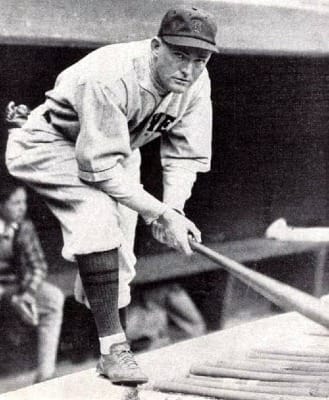

"People didn't pay to see me field," Hornsby reportedly said. "They paid to see me hit."

Rogers Hornsby stands alone at second base. The numbers say so. The eye test confirms it. And nearly a century after his prime, his legacy remains untouchable.

"I don't like to sound egotistical," Hornsby once said, "but every time I stepped to the plate, I expected to get a hit."

That wasn't arrogance -- it was a reasonable expectation. The man they called "The Rajah" hit .358 across 23 major league seasons. He won seven batting titles, including six straight. He captured two Triple Crowns, a feat no other National Leaguer has matched. And he posted a .577 career slugging percentage from second base, a position traditionally manned by slap hitters and defensive specialists.

But the story of Rogers Hornsby goes beyond just statistics. It's about a complex, difficult man whose genius at the plate came with plenty of rough edges. It's about a player who refused to compromise -- with teammates, management, or himself. And it's about how that uncompromising approach produced perhaps the greatest right-handed hitter in baseball history.

Let's dive into the remarkable career of Rogers Hornsby -- the good, the bad, and the otherworldly.

The Early Years: From Country Boy to Big Leaguer

Rogers Hornsby was born on April 27, 1896, in Winters, Texas, a small town about 200 miles west of Dallas. His father, a rancher and brick contractor, died when Rogers was two, leaving his mother to raise six children. Baseball became young Rogers' escape.

"I grew up in the country," Hornsby later recalled. "We didn't have any movies or anything like that, so baseball was it."

Hornsby dropped out of school after seventh grade and began playing semi-pro ball around Texas. His big break came in 1914 when he signed with the Denison Champions of the Western Association. After hitting .232 in 113 games, the 18-year-old caught the attention of the St. Louis Cardinals, who purchased his contract for $500.

Hornsby's MLB debut on September 10, 1915, gave little indication of what was to come. Standing 5'11" and weighing just 155 pounds, he hit a modest .246 in 18 games. The Cardinals weren't exactly impressed -- they tried converting him to shortstop the following year, where he struggled both at the plate (.313 OBP) and in the field (52 errors in 146 games). [Correction: He committed those 52 errors in 136 games at shortstop in 1916. A minor but good detail to have precise.]

"I was a lousy shortstop," Hornsby admitted years later. "But I could always hit."

That hitting ability soon became impossible to ignore. In 1919, now a full-time second baseman, Hornsby batted .318 and showed flashes of power with 8 home runs -- a solid total in the dead-ball era. The next year, as baseball entered the lively ball era, Hornsby exploded with a .370 average, leading the National League.

He was just getting started.

The Incredible 1920s: Hitting Like No One Before or Since

From 1921 to 1925, Rogers Hornsby put together a five-year stretch of offensive dominance that has never been equaled. The numbers almost look like typos:

• 1921: .397 BA, 21 HR, 126 RBI, 1.145 OPS, 185 OPS+

• 1922: .401 BA, 42 HR, 152 RBI, 1.181 OPS, 207 OPS+

• 1923: .384 BA, 17 HR, 83 RBI, 1.066 OPS, 187 OPS+

• 1924: .424 BA, 25 HR, 94 RBI, 1.203 OPS, 222 OPS+

• 1925: .403 BA, 39 HR, 143 RBI, 1.245 OPS, 210 OPS+

Let's put those numbers in perspective. Hornsby's .424 average is the highest single-season mark of the 20th century in the National League. Hornsby's .358 career average ranks second all-time to Ty Cobb's .366. And his .577 career slugging percentage as a second baseman is unmatched at the position.

Using sabermetrics, Hornsby's peak becomes even more impressive. His 173 career wRC+ (weighted runs created plus) means he created 73% more runs than the average player after adjusting for park and era factors. That's not just the best among second basemen -- it's the 11th best in baseball history.

"The most amazing thing about Hornsby was that he hit for that kind of average with that kind of power," baseball historian Bill James has noted. "Typically, you sacrifice some average to hit for power. Hornsby didn't sacrifice anything."

Hornsby's approach at the plate was unorthodox by modern standards. He crowded the plate, choking up slightly on the bat, and stood in an open stance. His unique eye training bordered on obsession -- he refused to read books, watch movies, or do anything he believed might strain his eyes. Card playing was out. So was drinking. Hornsby focused solely on seeing the baseball.

"I don't want to play golf," he famously said. "When I hit a ball, I want someone else to go chase it."

Those sacrifices paid off with otherworldly plate discipline and contact ability. In 1924, Hornsby struck out just 32 times in 536 at-bats. His 12.4% career strikeout rate would place him among the best contact hitters in today's game. And his .434 career on-base percentage trails only 10 players in baseball history.

Most impressively, Hornsby's greatest seasons came when he was player-manager of the Cardinals, juggling lineup decisions and pitching changes with his own at-bats. In 1925, his second full season as player-manager, Hornsby led the Cardinals to a 77-76 record while winning his second Triple Crown.

Branch Rickey, then the Cardinals' general manager, said, "Hornsby could hit .300 with a fountain pen."

The Defensive Question: How Good Was Hornsby in the Field?

When discussing Rogers Hornsby, defense is where the conversation gets complicated. Modern defensive metrics suggest Hornsby was a below-average fielder, posting -13.1 career defensive WAR. Contemporary accounts were mixed -- some praised his range and hands, while others criticized his lack of quickness and arm strength.

"Hornsby wasn't the smoothest second baseman," teammate Jim Bottomley once said, "but he got to balls you wouldn't expect, and he was smart enough to position himself right."

The truth likely falls somewhere in between. Hornsby committed 546 errors in his career, a high number even for his era. But he also led NL second basemen in assists six times and in double plays twice. He had good hands but limited range, especially later in his career as he put on weight.

What's indisputable is that any defensive limitations were massively outweighed by his offensive contributions. Using modern advanced metrics, Hornsby produced 127.0 career WAR (Baseball Reference version), ranking 9th all-time among position players. His 1924 season (12.1 WAR) ranks as one of the greatest individual seasons in baseball history.

As a point of comparison, Chase Utley, a modern defensive standout at the position, often produced more than 2 WAR of defensive value in his peak seasons. Even if we assume Hornsby was 2 WAR worse than average defensively each year, his offense was so dominant that he'd still rank among the greatest players ever.

"People didn't pay to see me field," Hornsby reportedly said. "They paid to see me hit."

The Wandering Years: Seven Teams in Seven Seasons

Despite his incredible production, Hornsby's personality caused nearly as much trouble as his bat caused for pitchers. After the 1926 season, in which he led the Cardinals to their first World Series title as player-manager, Hornsby demanded a three-year contract at $50,000 per year. When Cardinals owner Sam Breadon refused, Hornsby was shockingly traded to the New York Giants.

"I've always just been myself," Hornsby said of his blunt personality. "If you don't like it, that's your problem."

The trade kicked off a bizarre seven-year stretch in which Hornsby played for six different teams: The trade kicked off a bizarre stretch that saw him play for the New York Giants (1927), Boston Braves (1928), and Chicago Cubs (1929-32) before a brief return to the Cardinals (1933) and a final stop with the St. Louis Browns (1933-37).

Hornsby's production remained outstanding during these years, though not quite at his peak level. With the Cubs in 1929, he hit .380 with a 1.139 OPS and won his second MVP award. Yet despite his continued excellence, teams kept moving on from the aging star.

"Hornsby was a great player, but he wore out his welcome everywhere he went," said baseball writer Fred Lieb. "He told the truth as he saw it, and most people don't want to hear the truth."

His Cubs teammates reportedly took a vote on whether to accept their World Series shares with or without Hornsby (who was released late in the 1932 season). The vote was 19-4 against giving Hornsby a share, a damning indictment of how his teammates felt about him.

Bob O'Farrell, who caught for Hornsby on both the Cardinals and Cubs, summed it up: "A great hitter, maybe the greatest right-handed hitter ever. But as a person, as a teammate? No thanks."

The problems weren't just interpersonal. Hornsby had a gambling problem, betting heavily on horse races. While no evidence suggests he ever bet on baseball games, his financial issues added to his difficulties with team owners and likely contributed to his constant movement between teams.

The Twilight and Beyond: Hornsby as Manager

As Hornsby's playing career wound down in the mid-1930s, he transitioned to full-time managing. His managerial record was decidedly mixed -- in parts of 15 seasons with the Cardinals, Giants, Braves, Cubs, Browns, and Reds, he compiled a 701-812 record (.463 winning percentage).

Hornsby's managerial style mirrored his personality: uncompromising, blunt, and often controversial. He had little patience for players who didn't match his own dedication and work ethic.

"Hornsby was a drill sergeant as a manager," recalled Monte Irvin, who played under him briefly. "He expected everyone to be as good as he was, which wasn't possible."

His stint with the St. Louis Browns (1952-53) was particularly disastrous. Browns owner Bill Veeck hired Hornsby despite warnings about his personality, then fired him after 51 games of the 1953 season. Veeck claimed that every player on the team had individually asked for Hornsby to be dismissed.

"The players pulled together," Veeck said afterward, "but only in their universal dislike for Hornsby."

After his firing by the Browns, Hornsby never managed in the majors again. He spent several years managing in minor leagues and briefly coached for the Mets in 1962. He remained around baseball as a hitting instructor into his final years.

Hornsby was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1942, receiving 78.1% of the vote in his fifth year on the ballot. His relatively slow path to Cooperstown likely reflected his personality conflicts rather than any questions about his playing credentials.

Rogers Hornsby died of a heart attack on January 5, 1963, at age 66 in Chicago. True to his character, he was watching a college basketball game on television when he passed away -- one of the few forms of entertainment he allowed himself.

The Impossible Comparisons: Hornsby vs. Modern Second Basemen

To truly appreciate Hornsby's dominance, we need to see how he stacks up against the greatest second basemen of all time. Using advanced metrics that adjust for era and ballpark, the gap between Hornsby and his competition becomes clear:

Career wRC+ (weighted runs created plus):

• Rogers Hornsby: 173

• Nap Lajoie: 149

• Eddie Collins: 142

• Joe Morgan: 132

• Jose Altuve: 129 (still active in MLB)

• Charlie Gehringer: 124

• Roberto Alomar: 118

• Chase Utley: 118

• Ryne Sandberg: 114

(wRC+ statistics are courtesy of Fangraphs)

Hornsby's seven-year peak WAR of 73.5 was 24% more valuable than Joe Morgan's (59.3). That 14.2 WAR gap is roughly the value of Ernie Banks' entire 1959 MVP season. That's roughly the difference between Mike Trout and Andrew McCutchen.

Peak 7-Year WAR (Baseball Reference):

• Rogers Hornsby: 73.5

• Eddie Collins: 53.4

• Joe Morgan: 59.3

• Nap Lajoie: 52.3

• Chase Utley: 49.1

• Charlie Gehringer: 47.5

• Ryne Sandberg: 43.9

• Roberto Alomar: 38.5

• Jose Altuve: 38.1 (currently playing in MLB)

Hornsby's seven-year peak was 24% more valuable than Morgan's, his closest competitor. This gap highlights how Hornsby didn't just accumulate value over a long career -- his best seasons were on another level entirely.

Career OPS+:

• Rogers Hornsby: 175

• Eddie Collins: 141

• Nap Lajoie: 150

• Charlie Gehringer: 124

• Joe Morgan: 132

• Roberto Alomar: 116

• Chase Utley: 118

• Ryne Sandberg: 114

• Jose Altuve: 127

Again, Hornsby's adjusted OPS stands far above any other second baseman in history. The 25-point gap between him and Lajoie is approximately the difference between Willie Mays and Ken Griffey Jr.

"When you look at second basemen, there's Rogers Hornsby, and then there's everyone else," Bill James wrote in his Historical Baseball Abstract. "The gap between Hornsby and the second-best second baseman is probably bigger than the gap at any other position."

Even by WAR7 (seven best seasons), Hornsby (73.5) towers over second-place Joe Morgan (59.3). That 14.2 WAR gap is approximately the value of Ernie Banks' entire MVP season in 1959.

So where does this leave us? If we were to build an all-time team, Hornsby would be the obvious choice at second base. His offensive production wasn't just great for his position -- it ranks with the greatest hitters at any position in baseball history.

Could Hornsby Succeed in Today's Game?

One fascinating thought experiment is to imagine Rogers Hornsby playing in today's MLB. How would his skills translate to the modern game?

Hornsby's plate discipline and contact ability would certainly translate well. In an era where strikeouts have reached record levels, a hitter who rarely swings and misses would be enormously valuable. His career 12.4% strikeout rate would place him among the elite contact hitters in today's game.

His power would also play well in any era. Hornsby's isolated power (ISO) of .218 would rank among the top 25 active players, and that's without adjusting for the much lower power environment of his era. If we adjust for era, Hornsby's power might translate to 40+ home runs annually in today's game.

The bigger question marks would be defense and personality. Modern defensive metrics and video analysis would likely expose Hornsby's limitations in the field more clearly. And his abrasive personality would clash with modern media demands and team chemistry priorities.

"Hornsby would hit .330 with 35 homers today," says baseball analyst Dan Szymborski. "But he'd also be a daily headache for any manager and PR department."

Would teams tolerate Hornsby's personality for his bat? Almost certainly, just as they did in his day. But he might find himself moving between teams just as frequently as he did in the 1920s and 30s.

One factor working in Hornsby's favor: modern analytics would love him. His combination of on-base ability and power produced a career 1.010 OPS -- a dream profile for today's front offices.

The Hornsby Approach: His Hitting Philosophy

One area where Hornsby left a lasting legacy was his approach to hitting. As a manager and instructor, he developed clear principles that he passed on to younger players:

- See the ball clearly. Hornsby's obsession with protecting his eyesight is legendary. He refused to read books, watch movies, or play cards, believing they would strain his eyes. While extreme, his emphasis on vision training was decades ahead of its time.

- Get a good pitch to hit. Hornsby was selectively aggressive, hunting pitches he could drive rather than settling for contact. "I never took a pitch in my life," he claimed, though his solid walk rates suggest otherwise. What he meant was that he was always looking to hit, not just to make contact. [Excellent clarification of this famous quote.]

- Hit the ball where it's pitched. Despite his power numbers, Hornsby wasn't a pure pull hitter. He used the entire field, driving outside pitches to right field and pulling inside pitches with authority.

- Practice with purpose. Hornsby believed in quality over quantity in batting practice. "Don't just swing to be swinging," he told players. "Have a purpose with every swing."

- Know the situation. As a player-manager, Hornsby was acutely aware of game situations. He tailored his approach based on score, inning, and runners on base -- a level of situational awareness that modern analytics have sometimes deemphasized.

Ted Williams, often considered the greatest hitter who ever lived, credited Hornsby as a major influence. "Rogers Hornsby was the only guy who ever talked hitting with me that I really listened to with 100 percent conviction," Williams said.

Jose Altuve (2B, HOU), perhaps the closest modern equivalent to Hornsby in terms of hitting ability from the second base position, has spoken about the importance of studying the game's history. His hitting style—built on balance, quick hands, and using the whole field—draws from the same fundamental principles that made Hornsby a legend, demonstrating how much can still be learned from him.

The Dark Side: Hornsby's Reputation and Character

No honest accounting of Rogers Hornsby can ignore the more problematic aspects of his personality and character. By nearly all accounts, Hornsby was difficult, abrasive, and often openly hostile to those around him.

"He was the greatest right-handed hitter God ever made," said longtime baseball writer Fred Lieb, "and God made him grumpy about it."

Hornsby's issues went beyond just being "grumpy." He was known for racist views common to his era, refusing to shake hands with Jackie Robinson when Robinson broke baseball's color barrier. As a manager, he openly berated players and showed little empathy for their struggles.

His gambling on horse races, while not involving baseball, showed poor judgment and led to financial problems throughout his life. He was sued multiple times for unpaid debts and tax issues.

Yet when discussing the greatest players in baseball history, Hornsby must be included -- not because he was a good person, but because his on-field performance demands it. Like Ty Cobb, another all-time great with serious character flaws, Hornsby's legacy exists in that uncomfortable space where brilliant talent meets deeply flawed humanity.

"You don't have to be a nice guy to be a great hitter," baseball historian Donald Honig once wrote. "Rogers Hornsby proved that every day of his career."

The Hornsby Effect: His Impact on Second Base Play

Before Hornsby, second basemen were typically light-hitting defensive specialists. The position was seen as defense-first, with any offensive contribution considered a bonus. Hornsby shattered that paradigm, showing that a second baseman could be the most dangerous hitter in a lineup.

While not immediate, Hornsby's success eventually influenced how teams viewed the position. Charlie Gehringer, a Hall of Famer who followed Hornsby, was a much more complete offensive player than second basemen of the pre-Hornsby era. Later stars like Joe Morgan, Ryne Sandberg, and Roberto Alomar combined offensive production with defensive excellence in ways that might not have seemed possible without Hornsby expanding the position's offensive expectations.

"Hornsby changed how we think about second base," baseball historian John Thorn has noted. "He showed that a middle infielder could be an offensive force, not just a defensive specialist."

In today's game, offensive-minded second basemen like Jose Altuve, Jeff Kent, and Marcus Semien owe a debt to Hornsby for expanding the offensive potential of the position. While none approach Hornsby's offensive dominance, they've benefited from the expanded view of what a second baseman can be.

Kent, whose 377 home runs are the most by any second baseman in MLB history, once said: "I looked at guys like Hornsby and realized second basemen could be run producers, not just table-setters. That shaped my whole approach.

Part 2 Tomorrow: Hornsby's Statistical Legacy, The Final Verdict: Hornsby's Place in Baseball History, "I'm Not Here to Make Friends"