The Hitless Wonders of '67: How the White Sox Defied Baseball Logic

The 1967 Chicago White Sox represent one of baseball's most fascinating statistical anomalies. Despite being outscored by their opponents over the course of the season—a formula that almost always results in a losing record—the Sox remained locked in a heated pennant race until the final weekend, finishing just three games behind the "Impossible Dream" Boston Red Sox with an 89-73 record.

Their 17-game overperformance of their Pythagorean expected record is one of the largest in baseball history. But how did they do it? How did a team that should have lost more games than it won nearly capture the American League flag? The answer lies in a unique blueprint of elite pitching, airtight defense, and a gritty mastery of the one-run game.

The Statistical Puzzle: Numbers That Don't Add Up

To understand the magic of the '67 White Sox, you first have to appreciate the statistical madness. The team's profile was a study in extremes that seems to defy the basic math of baseball:

|

Category |

White Sox Total |

AL Rank |

Notes |

|

Runs Scored |

531 |

10th (last) |

162 fewer than league average |

|

Runs Allowed |

550 |

1st |

143 fewer than league average |

|

Run Differential |

-19 |

5th |

Only team in MLB history with a

negative run differential to win 89+ games |

|

Pythagorean Record |

76-86 |

- |

Based on run differential |

|

Actual Record |

89-73 |

4th |

17-game overperformance |

The Sox scored the fewest runs in the American League while simultaneously allowing the fewest. This profound imbalance created a team that played an extraordinary number of nail-biters—and somehow, against all odds, won far more than they lost.

"We knew we weren't going to score many runs," White Sox pitcher Tommy John recalled. "Every game, we figured we needed to hold the other team to two runs or fewer to have a chance."

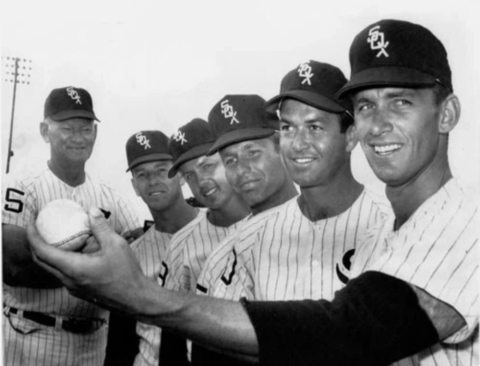

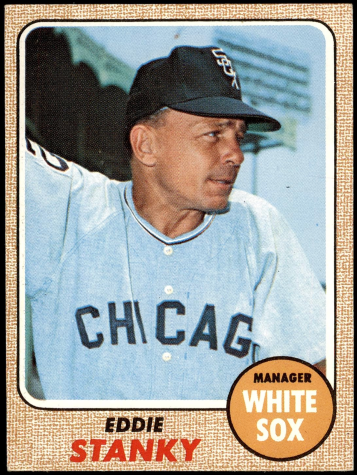

The Eddie Stanky Factor: A Masterclass in Small Ball

At the helm was manager Eddie Stanky, who had a clear-eyed understanding of his team's glaring limitations and hidden strengths. Known as "The Brat" during his playing days, Stanky was a fiery, confrontational tactician who built his team's identity around baseball's most aggressive small-ball strategies.

Stanky’s approach was tailored perfectly to his personnel:

- Aggressive Base Running: The White Sox stole 102 bases (2nd in AL) despite having few true speed merchants. More importantly, Stanky was a devotee of the hit-and-run, constantly putting runners in motion, even with two strikes.

- The Squeeze Play: Chicago led the league with an astonishing 32 successful squeeze bunts, many of them coming in the tense, late innings of tight games.

- Advanced Defensive Positioning: Decades ahead of his time, Stanky often positioned his fielders based on detailed scouting reports of opposing hitters' tendencies.

- Modern Bullpen Usage: Stanky used his relievers situationally rather than in fixed roles, often bringing in his best pitcher to face the biggest threat, regardless of the inning.

"Eddie Stanky squeezed every possible run out of that offense," Yankees manager Ralph Houk said after a series against Chicago. "They don't beat themselves, and they make you beat their pitching, which almost nobody could do."

Stanky's managerial style forged a team perfectly designed to win close, low-scoring games—exactly the formula needed to overcome a negative run differential.

The One-Run Game Phenomenon

The secret to Chicago's defiance of the odds lay in their uncanny ability to win the nail-biters. Their record in one-run games wasn't just good; it was historically great:

|

Game Type |

Record |

Win Percentage |

|

One-Run Games |

35-16 |

.686 |

|

Two-Run Games |

17-14 |

.548 |

|

All Other Games |

37-43 |

.463 |

A .686 winning percentage in one-run games is among the highest ever recorded for a full season. For context, the league-average winning percentage in these coin-flip games typically hovers right around .500. The White Sox were playing a different game.

"We were comfortable in tight games," White Sox shortstop Ron Hansen explained years later. "We played so many of them that there was never any panic. If we were tied or down a run in the eighth inning, we actually felt confident."

This comfort in close games was reflected in their performance when the pressure was highest:

|

Situation |

White Sox |

Opponents |

|

Batting, Close & Late |

.238/.309/.321 |

.195/.272/.255 |

|

Pitching, Close & Late |

2.03 ERA |

3.98 ERA |

|

Batting w/ RISP |

.249 |

.215 |

Despite their offensive anemia, the White Sox consistently outperformed their opponents in these high-leverage situations. While such "clutch" performance is typically not sustainable, for one magical, logic-defying year, they found a way to deliver when it mattered most.

The Elite Pitching Staff: Baseball's Best Arms

The bedrock of this improbable contender was its historically excellent pitching staff. Led by a trio of elite starters and a deep, versatile bullpen, the White Sox posted a team ERA of 2.45—not only the best in baseball in 1967 but one of the best of the modern era.

Their top performers were nothing short of brilliant:

Joe Horlen (RHP, CHW)

- 19-7, 2.06 ERA (179 ERA+), 0.95 WHIP, 6.0 WAR

- Led AL in ERA and WHIP

- 4 shutouts, 15 complete games

- Allowed only 9 home runs in 258 innings

Horlen's season ranks among the greatest pitching performances of the 1960s. Utilizing a devastating sinker and pinpoint control, he induced weak contact all season long, posting a ground ball rate near 55%. "Joe's sinker was the best I've ever seen," teammate Tommy John said. "When he was on, it was like hitting a bowling ball."

Gary Peters (LHP, CHW)

- 16-11, 2.28 ERA (162 ERA+), 1.04 WHIP, 5.0 WAR

- 215 strikeouts (career high)

- 5 shutouts, 14 complete games

- Left-handed batters hit just .198 against him

Peters was a workhorse who combined power and finesse, pairing a high strikeout rate with one of the league's best pickoff moves. His ability to work deep into games preserved the bullpen for Stanky's tactical deployments. "Gary could beat you with power or with finesse," catcher J.C. Martin recalled. "Most days he had both working."

Tommy John (LHP, CHW)

- 10-4, 2.48 ERA (149 ERA+), 1.11 WHIP, 2.9 WAR

- Limited home runs (just 6 in 178 innings)

- 59% ground ball rate (led rotation)

- 2.14 ERA in Comiskey Park

Years before the famous surgery that would bear his name, John was already an incredibly effective ground ball specialist. His extreme ground ball tendencies played perfectly into the hands of Chicago's excellent infield defense.

Hoyt Wilhelm (RHP, CHW)

- 8-3, 1.31 ERA (283 ERA+), 0.87 WHIP, 4.4 WAR

- 12 saves in 49 appearances

- Allowed just 5 extra-base hits in 89 innings

- Opponents batted a minuscule .162 against his knuckleball

At age 44, the ageless Wilhelm remained arguably baseball's most unhittable reliever. His legendary knuckleball allowed him to pitch multiple innings at a time, making him Stanky's ultimate high-leverage weapon. "Hitting Wilhelm's knuckleball was like trying to catch a butterfly with chopsticks," Detroit slugger Willie Horton once said. "You might get lucky occasionally, but mostly you just look foolish."

This pitching dominance gave the White Sox a chance to win every single day, even with minimal run support. When scoring just three runs, most teams expect to lose. The 1967 White Sox went 24-18 in such games—a .571 winning percentage.

Defensive Excellence: Saving Runs with Gloves

Chicago's exceptional defense was the perfect complement to its pitching. While advanced defensive metrics from 1967 are limited, the available data and contemporary accounts paint a clear picture of an elite unit:

|

Position |

Primary Starter |

Defensive Strength |

|

Catcher |

J.C. Martin |

42% caught stealing (league avg:

35%) |

|

First Base |

Tommy McCraw |

+7 Defensive Runs Saved (estimated) |

|

Second Base |

Don Buford |

+12 Defensive Runs Saved (estimated) |

|

Shortstop |

Ron Hansen |

Led AL shortstops in fielding

percentage |

|

Third Base |

Don McMahon |

+5 Defensive Runs Saved (estimated) |

|

Left Field |

Walt Williams |

Average range, strong arm |

|

Center Field |

Tommie Agee |

Gold Glove winner, +18 DRS

(estimated) |

|

Right Field |

Ken Berry |

+13 Defensive Runs Saved (estimated) |

The White Sox led the American League with a .981 fielding percentage and turned 181 double plays (2nd in AL). Their outfield defense, anchored by the brilliant Tommie Agee in center, covered enormous ground in spacious Comiskey Park. The effect of this defensive web was profound: ground balls became outs more consistently, rallies were killed by double plays, and would-be extra-base hits died in the outfield grass.

"Our pitchers knew they didn't have to strike everyone out," Hansen explained. "Put the ball in play, and we'd make the plays behind them."

The Home Field Advantage: The Cauldron of Comiskey

Comiskey Park itself played a significant role in the White Sox's ability to win close games. The ballpark's dimensions and playing surface were tailored perfectly to the team's strengths:

- A spacious outfield that turned doubles in the gap into long singles.

- Infield grass kept deliberately high to slow down ground balls and aid the defense.

- Heavy, damp air, particularly in night games, that suppressed home runs.

- Winds that often blew in from the outfield, knocking down fly balls.

The Sox leveraged these conditions to go 45-36 at home (.556) despite scoring just 245 runs in 81 home games—an average of only 3.0 runs per game.

"Comiskey Park was like our secret weapon," pitcher Gary Peters recalled. "We knew exactly how to use those conditions to our advantage, and visitors hated playing there."

Situational Hitting: Manufacturing Runs from Thin Air

While the White Sox offense was undeniably poor overall, they were masters of execution. They excelled in the precise situations that manufactured runs from thin air, maximizing their limited opportunities:

|

Situation |

White Sox Avg |

AL Avg |

Difference |

|

Runners on 3rd, less than 2 outs |

.354 |

.310 |

+.044 |

|

Advancing runners (productive outs) |

38.2% |

31.5% |

+6.7% |

|

Successful sacrifice bunts |

86 |

52 (avg) |

+34 |

These situational advantages allowed Chicago to plate runs in ways that traditional statistics don't fully capture. When they got a runner to third base with less than two outs, they were remarkably efficient at bringing that runner home.

"We practiced situational hitting constantly," outfielder Ken Berry recalled. "Moving runners over, hitting behind runners, executing the squeeze—those were our offensive weapons."

The Mental Edge: An Expectation to Win

Beyond the tangible factors, the 1967 White Sox developed a powerful psychological edge. They didn't just hope to win the tight ones; they expected to.

"We never thought we were out of a game if it was close," Don Buford explained. "We'd been in so many one-run games that nothing fazed us in the late innings."

This mental toughness showed up in the box score:

- Late-Inning Dominance: The White Sox outscored opponents 132-94 from the 8th inning onward.

- Extra Inning Success: Chicago went 12-7 in extra-inning contests.

- Comeback Kids: Despite their offensive limitations, the Sox clawed back for 34 come-from-behind victories.

- Resilience: The team rarely endured long losing streaks, posting a 31-23 record in games following a loss.

Manager Eddie Stanky fostered this mentality with his combative, chip-on-the-shoulder approach. He created an "us against the world" attitude that his players eagerly bought into.

"Eddie made us believe we could win with pitching and defense," Tommy John said. "He convinced us that our style of baseball was superior, even if it wasn't flashy."

Tactical Innovation: Stanky's Bullpen Revolution

One of the most overlooked factors in Chicago's success was Stanky's ahead-of-his-time bullpen management. While most managers of the era used relievers in fixed roles, Stanky deployed his arms like a chess master, based on leverage and matchups:

- Hoyt Wilhelm appeared in the 6th inning or earlier 16 times when the game was on the line.

- Bob Locker was used as a specialist against right-handed power hitters, regardless of the inning.

- Wilbur Wood often entered to face a key left-handed batter in a high-leverage spot.

- Don McMahon was brought in specifically to get ground-ball double plays.

This flexible approach allowed Chicago to navigate the treacherous late innings more effectively than their opponents, who typically saved their best reliever for a 9th-inning save situation that sometimes never came.

"Eddie used us when the game was on the line, not based on some formula," Hoyt Wilhelm explained. "If their big hitters were up in the seventh inning of a one-run game, that's when he wanted his best reliever in there."

The Unsustainable Model: Why the Magic Couldn't Last

But this brand of baseball, as brilliant as it was in 1967, was a tightrope walk over a canyon. It proved utterly unsustainable. Several factors explain why the magic vanished:

- Regression to the Mean: Extreme performance in one-run games almost always regresses toward .500. In 1968, Chicago's record in those games fell to 21-25.

- Aging Pitching Staff: Key pitchers like Wilhelm (44) and McMahon (37) simply couldn't defy Father Time forever.

- An Anemic Offense: Even in the pitching-dominated 1960s, scoring just 3.3 runs per game was not a viable long-term strategy for winning.

- Tactical Adjustments: Opponents began adapting to Stanky's small-ball, holding runners closer and better defending his signature squeeze plays.

- A Widening Talent Gap: As other AL teams improved, Chicago's offensive deficiencies became more glaring.

In 1968, despite another strong pitching performance (2.68 team ERA), the White Sox collapsed to a 67-95 record. Their Pythagorean record that year was 75-87, meaning they underperformed by 8 games—an almost perfect reversal of their 1967 fortune.

"Baseball has a way of evening things out," a reflective Eddie Stanky said after being fired midway through the 1968 season. "The breaks we got in '67 went against us in '68."

The Broader Context: An Anomaly Among Anomalies

To appreciate just how unusual the 1967 White Sox were, it helps to compare them to other famous overachievers:

|

Team |

Run Diff |

Pyth W-L |

Actual W-L |

Difference |

|

1967 White Sox |

-19 |

76-86 |

89-73 |

+13 |

|

1984 Mets |

+8 |

82-80 |

90-72 |

+8 |

|

2007 Diamondbacks |

-20 |

76-86 |

90-72 |

+14 |

|

2012 Orioles |

+7 |

82-80 |

93-69 |

+11 |

|

2016 Rangers |

+8 |

82-80 |

95-67 |

+13 |

What sets the '67 White Sox apart is the sheer extremity of their offensive futility. Their 531 runs scored was the lowest total for any team that finished with a winning record in the entire span from 1920 to 1972.

"What made those White Sox special wasn't just that they won more games than they should have," baseball analyst Bill James wrote years later. "It was that they did it with perhaps the weakest offense of any contending team in modern baseball history."

The Legacy: A Model of Efficiency

Despite their ultimate failure to win the pennant, the 1967 White Sox remain a fascinating case study in baseball efficiency. They extracted the maximum possible value from limited resources through a masterful combination of elite pitching, superior defense, tactical innovation, and unshakable mental toughness.

In some ways, they were a team far ahead of their time. Many of Stanky's methods—particularly his fluid bullpen usage and data-driven defensive positioning—would become standard practice decades later.

"Looking back, you can see elements of today's analytics-driven strategies in how those White Sox played," modern baseball executive Theo Epstein observed. "They understood their limitations and built a strategy that maximized their specific talents."

For baseball historians and analysts, the 1967 White Sox remain a compelling puzzle—a team that defied statistical gravity and nearly rode its imbalanced approach all the way to the World Series. They are the ultimate exception that proves the rule about run differential, a team that left an indelible mark on baseball history as one of the sport's most intriguing anomalies—a group of "Hitless Wonders" who turned the most extreme version of "small ball" into a legitimate pennant contender.