The Spectacular Rise and Tragic Fall of Ed Delahanty: Baseball's First Superstar

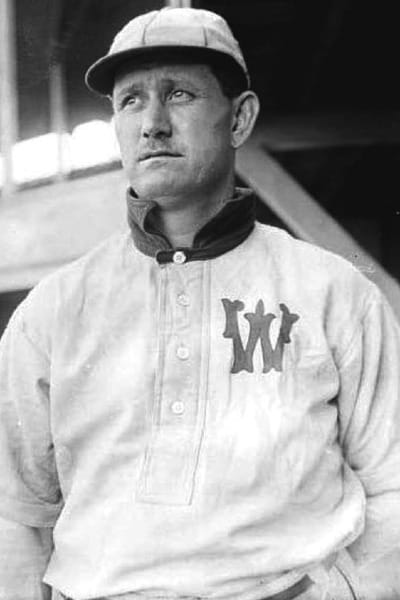

The morning of July 9, 1903, brought shocking news to the baseball world. A body had been recovered from the churning waters at the base of Niagara Falls. It was Ed Delahanty. Known as "Big Ed" to fans across America, he was dead at 35. He had plunged to his death under mysterious circumstances seven days earlier.

It was a stunning end for baseball's greatest hitter of the 1890s. This was a man who had owned the game like few others before or since. Newspapers across the country ran front-page headlines. And the baseball world faced a tragedy that, more than a century later, still raises questions.

"When you pitch to Delahanty, you just want to shut your eyes, say a prayer and chuck the ball," said pitcher Crazy Schmit. "The Lord only knows what'll happen after that."

The story of Ed Delahanty has both spectacular achievement and deep tragedy. It's a tale of remarkable hitting, turbulent early life, and personal struggles that led to a fateful night on a bridge spanning two nations. Let's look at the life and mysterious death of baseball's first true superstar.

The Early Years: Baseball in the Blood

Edward James Delahanty was born on October 30, 1867, in Cleveland, Ohio, to Irish immigrant parents. He was the oldest of seven brothers, five of whom would play major league baseball. That's a record that still stands today.

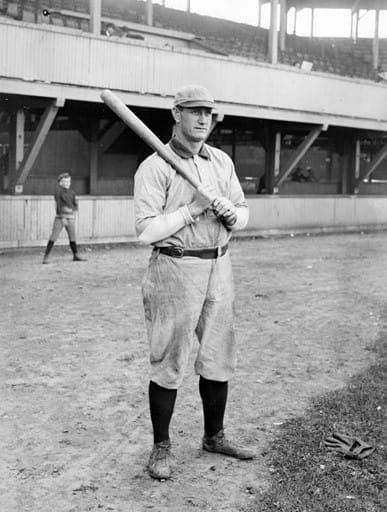

Ed grew up in a working-class neighborhood where baseball was more than recreation. It was a ticket to a better life. By his late teens, he had grown into a powerful 6'1", 170-pound athlete with unusual bat speed.

"The Delahanty boys seemed born to play ball," said teammate Tommy McCarthy. "But Ed had something special from the start. Those wrists, that swing, the way the ball jumped off his bat."

In 1887, the 19-year-old Delahanty signed with Mansfield of the Ohio State League, batting .351 with 90 runs scored in 83 games. After a brief stint with Wheeling in the Tri-State League, where he hit .412 in 21 games, the Philadelphia Phillies purchased his contract in May 1888 for approximately $2,000. It was a substantial sum in an era when most workers earned far less.

His major league debut came on May 22, 1888. His first season was unremarkable. He hit just .228 in 74 games with only one home run. The next year he improved to .293 in 56 games, but still hadn't found his groove.

In 1890, Delahanty jumped to the Cleveland Infants of the upstart Players League, batting .296 in 115 games. When that league folded after one season, he returned to Philadelphia. The Phillies were willing to forgive the 22-year-old prospect. But 1891 brought another disappointing season, a .243 average that had some questioning whether he'd ever reach his potential.

Then something changed.

The Rise to Stardom: A Hitting Machine

After more than three years in the majors without living up to expectations, Delahanty rededicated himself. He worked out every day in the offseason. He reported to camp in 1892 in the best shape of his life. The results were immediate.

He batted .306 while leading the league in triples (21) and slugging percentage (.495). His OPS+ of 157 showed he was finally producing at an elite level. It was the breakthrough season he needed.

But 1893 was when Delahanty truly arrived. The league had moved the pitcher's mound back to 60 feet, 6 inches, and batting averages soared across baseball. Nobody took better advantage than Big Ed. He hit .368 with 19 home runs and 146 RBI. He led the league in homers, RBI, total bases (347), and slugging percentage (.583). His OPS+ of 164 ranked him among the game's most productive hitters.

He narrowly missed the Triple Crown. Teammates Billy Hamilton and Sam Thompson led the league in batting with .380 and .370 respectively.

The 1894 season saw one of the most remarkable hitting displays in baseball history. The Phillies outfield featured four players batting over .400. Delahanty hit .404 (though he finished fourth in the league), Sam Thompson .407, Billy Hamilton .404, and spare outfielder Tuck Turner .416. Despite his .407 average in the official records, Boston's Hugh Duffy captured the batting title with an all-time record .440.

Bill James would later write, "Any way you cut it, the Phillies had the greatest outfield of the 19th century."

Delahanty's production continued at a staggering pace. In 1895, he batted .404 again, this time leading the league in doubles (49) and on-base percentage (.500). His OPS of 1.117 and OPS+ of 186 put him in rarified air. The next year, 1896, he led the league in doubles (44), home runs (13), RBI (126), and OPS (1.103) while hitting .397.

On July 13, 1896, Delahanty accomplished something truly special. Playing against Chicago at the West Side Grounds, he hit four home runs in a single game. He became just the second player in major league history to accomplish the feat. Two were hit into the bleachers. The other two were inside-the-park home runs. Remarkably, the Phillies lost 9-8. To this day, Delahanty remains the only player in history to hit four home runs in one game and four doubles in another game (May 13, 1899).

The 1897 season saw Delahanty hit .377 with 200 hits and 40 doubles. In 1898, he led the National League in stolen bases with a career-high 58 while batting .334 with 183 hits and 36 doubles. His speed and power combination made him a truly unique threat.

Then came 1899, perhaps his finest season. Delahanty won his first batting title with a .410 average. He added career highs in games played (146), hits (238), and doubles (55). His nine home runs and 137 RBI gave him another monster season. His OPS of 1.046 and OPS+ of 189 showed his complete dominance. He became the first player in major league history to hit .400 three times.

In 1900, Delahanty had what might be considered an "average" season by his standards, batting .323 with 174 hits. But he bounced back in 1901, once again leading the National League in doubles (38) and OPS (.955) while hitting .354 with 192 hits and 108 RBI.

Over his 13 seasons with Philadelphia, Delahanty had become more than just a great hitter. He was the face of the franchise. He was a five-tool player who could hit for average, hit for power, run, throw, and field. In an era where specialization was rare, Delahanty could do it all.

The Jump to Washington and the Money Chase

By 1901, Delahanty had spent 13 seasons with Philadelphia. Despite his success and his status as one of baseball's biggest stars, he was earning only $3,000 per year. The rival American League was offering better money and better treatment to players willing to jump leagues. Many of his teammates and opponents had already made the switch.

After batting .354 with 108 RBI for the Phillies in 1901, Delahanty decided to make the jump. He signed with the Washington Senators for $4,000 in 1902.

At 34 years old, he showed no signs of slowing down. He gave Washington instant credibility. He was named captain of his new club and joined friend Jimmy Ryan in the outfield. As a result of a judge's ruling, any players from the Phillies were forbidden from playing in the state of Pennsylvania. This prevented Delahanty and his fellow Philadelphia jumpers from playing against the Athletics. To get around the court order, Big Ed and the other jumpers would typically get off the train in Delaware and head to the team's next destination.

Big Ed battled former Phillies teammate Nap Lajoie of the Cleveland club for the batting crown in 1902. The race was close all season. Though unofficial figures at season's end showed Lajoie with a 15-point lead, .387 to .372, the official statistics released two months later declared Delahanty champion by a seven-point margin. [Note: This batting title claim is disputed in historical records - some sources credit Lajoie with the title. If accurate, this would have made Delahanty the only player ever to win batting titles in both the NL and AL.]

Regardless of the official ruling, Delahanty's 1902 season was outstanding. He led the league in doubles (43), on-base percentage (.453), and slugging percentage (.590). His OPS of 1.043 and OPS+ of 188 at age 34 showed he remained one of baseball's most feared hitters. He collected 178 hits and 14 triples while batting .376.

The money he'd been chasing, however, didn't last long. Delahanty had a serious gambling problem. He lost much of his salary at the racetrack. Stories spread of him blowing his savings on foolish bets.

The Unraveling: A Season Cut Short

The 1903 season started poorly for Delahanty. His drinking, which had been a problem throughout his career, had increased. His behavior became more erratic. He feuded with manager Tom Loftus over which outfield position he should play. Loftus wanted him in right field. Delahanty insisted he only play left.

The turmoil affected his performance. He was sent to a health spa in Michigan to shape up. When he returned on May 29, he continued to hit well, posting a .333 average in 156 at-bats over 42 games. But his demons were catching up with him.

He started giving away precious keepsakes, including his gold watch, to teammates. There were even rumors he had attempted suicide by turning on the gas in his hotel room in Washington. Whether these stories were true or exaggerated, they showed a man in crisis.

Prior to embarking on a road trip with the Senators on June 17, Delahanty took out a life insurance policy on himself, naming his daughter Florence as the beneficiary. It was an ominous sign.

On June 25, 1903, Delahanty played his final major league game in Cleveland. He had no way of knowing it would be his last.

New York Giants manager John McGraw, sensing Delahanty was down on his luck and unhappy in Washington, had been trying to lure him to New York. When a near-deal with the AL's New York Highlanders fell through, Big Ed began disappearing from the team for days at a time. The Senators had become used to his frequent absences.

The Fateful Journey: July 2, 1903

On the night of July 2, 1903, Delahanty left his team in Detroit. He left behind all his personal belongings except his Washington Senators uniform. He boarded Michigan Central Train No. 6 at 2:45 p.m., bound for New York. He reportedly hoped to negotiate a release from his contract and join the New York Giants, where McGraw had been courting him.

What happened next has been pieced together from conductor and witness accounts.

Delahanty consumed five shots of whiskey on the train. He became increasingly disruptive. He smoked when it was forbidden. He broke glasses by smashing a pane in an emergency tool cabinet. Some accounts say he brandished a straight razor, threatening passengers. He attempted to drag a sleeping woman from her berth by her ankles.

Train conductor John Cole had seen enough. Eight hours after boarding, at approximately 11 p.m., Cole stopped the train at Bridgeburg, on the Canadian side of the Niagara River across from Buffalo. Cole, along with several trainmen, pushed Delahanty down the hallway and off the train onto the International Railway Bridge. He handed him his hat and pointed toward the station.

"And don't make any trouble, you know you're still in Canada," Cole warned.

"I don't care whether I'm in Canada or dead," Delahanty responded.

The train, Michigan Central No. 6, disappeared into the night. Delahanty was left standing alone on the International Railway Bridge. The massive structure spanned 3,000 feet. Twenty-five feet below, the Niagara River roared on its way toward the falls.

It was almost 11 p.m. The night was dark.

Sam Kingston, a 70-year-old night watchman earning $1.74 a day, was on duty as bridge guard. He encountered Delahanty leaning against an iron truss on the bridge. Kingston, concerned for the man's safety, shined his lantern on Delahanty's face.

Big Ed, confused and heavily intoxicated, tripped on the railroad tracks. An altercation occurred between the two men. Kingston later claimed he tried to restrain Delahanty, but the baseball star broke free and ran off into the darkness.

Moments later, Delahanty wasn't on the bridge anymore.

Whether he fell, stumbled, jumped, or was pushed has never been determined. Kingston's account was the only one. He didn't report the incident until the next morning. Some have questioned whether the elderly watchman might have pushed Delahanty during their struggle, though Kingston would have been unlikely to overpower Big Ed even in a drunken state.

What is certain is that Ed Delahanty went into the Niagara River that night. His body began the long journey downstream toward Niagara Falls.

The Discovery and the Mystery

Delahanty's disappearance didn't immediately alarm anyone. The Senators, who had passed over the International Bridge less than an hour after their teammate's fall, had grown used to his absences. Even his wife, Norine, wasn't terribly worried when he failed to meet her at the train station. She was accustomed to his drinking and his tendency to go missing for days.

When the story of Delahanty's vanishing first broke, people assumed he had jumped to the New York club or was simply on a long bender somewhere. But as the days passed and repeated inquiries turned up nothing, the story took on a more serious tone.

The connection between Delahanty and the stranger on the bridge was finally made by John K. Bennett, manager for the Pullman Car Company. He investigated the contents of a dress suitcase and black leather bag sitting unclaimed in his Buffalo office. Inside he found a pair of high-top baseball shoes and a Washington Senators pass book.

It was Fourth of July weekend. Niagara Falls was packed with an estimated 15,000 tourists enjoying the holiday. None of them noticed a body as it plummeted over Horseshoe Falls.

On Thursday, July 9, 1903, seven days after Delahanty's fall, his body was found floating in the turbulent water at the base of Niagara Falls. William LeBlond, operator of the popular Maid of the Mist tour boat, made the grim discovery at the boat's landing on the Ontario side of the gorge.

The body was badly mangled and barely recognizable. One leg had been nearly severed, presumably by the tour boat's propeller. The stomach was split open, the intestines hanging out. All of Delahanty's clothes had been stripped off by the violent plunge over the falls, except for his silk necktie, shoes, and socks.

His brother Frank, who played for Syracuse, arrived to identify the body. The funeral was held on July 11 in Cleveland, the family's hometown. Red and white roses in the shape of a baseball bat covered the closed casket. Giants manager John McGraw served as a pallbearer.

Frank Delahanty questioned how Ed's tie could still be in place, yet all his diamond rings and money had vanished. The lack of money and jewelry on the body led to speculation about foul play. Some believed Sam Kingston had pushed the baseball star from the bridge after robbing him.

But the truth is likely simpler. Bodies that go over Niagara Falls are typically found with barely any clothes on, let alone valuables. The force of the water and the violence of the fall strip away almost everything.

Police eventually ruled Delahanty's death an accident. His family blamed the railroad conductor for forcing him off the train before it reached Buffalo, leaving him stranded on the bridge. Delahanty's widow sued the Michigan Central Railroad. She asked for $20,000 in damages. The jury awarded her $3,000 and her daughter $2,000.

The family had gotten $5,000. It was the amount Delahanty had hoped to earn from the Giants. Just not in the way anyone wanted.

The Legacy: Baseball's First Superstar

Ed Delahanty finished his 16-year career with a .346 batting average, the fifth-highest in major league history. He ranks behind only Ty Cobb (.366), Rogers Hornsby (.358), Joe Jackson (.356), and Lefty O'Doul (.349) in career batting average among players with significant playing time.

He collected 2,597 hits, 522 doubles, 185 triples, and 101 home runs. He drove in 1,466 runs and scored 1,600. He stole 456 bases. His career WAR of 69.6 ranks him among the game's all-time greats.

His career OPS of .917 and OPS+ of 152 put him in elite company. His career on-base percentage of .411 and slugging percentage of .505 showed he could both get on base and hit for power. In an era before the home run became baseball's dominant offensive weapon, Delahanty was a true five-tool player who could do everything on a baseball field.

He led the league in doubles five times, triples once, home runs twice, RBI three times, batting average twice (disputed), and slugging percentage three times. He's the only player in history to hit four home runs in one game and four doubles in another game.

He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1945 by the Old Timers Committee. No induction ceremony was held in Cooperstown at that time, though his plaque hangs today in the Hall.

John McGraw, who managed the Giants and was a pallbearer at Delahanty's funeral, was asked late in life how players of the 1920s and 1930s compared to those of his era.

"Ed Delahanty was as great a hitter as I have ever seen," was his reply.

The Sporting News wrote years after his death: "He was among the greatest batters the game ever produced."

The Man Behind the Legend

The truth is, Ed Delahanty was a complicated man. He was talented beyond measure. He was also troubled by demons he couldn't escape.

"Men who met him had to admit he was a handsome fellow," wrote sportswriter Robert Smith in the New York Times in 1903. "Although there was an air about him that indicated he was a roughneck at heart and no man to tamper with. He had that wide-eyed, half-smiling, ready-for-anything look that is characteristic of a certain type of Irishman."

Delahanty's struggles with alcohol were well known throughout his career. His gambling addiction cost him much of the money he earned. His erratic behavior in his final season showed a man in crisis.

Yet on the baseball field, he was nothing short of brilliant. He paved the way for generations of great hitters who followed him, including Ty Cobb and Babe Ruth. He showed that baseball could produce genuine superstars, players whose fame transcended the sport.

More than 120 years later, the exact circumstances of his death remain a mystery. Was it an accident? A drunken fall in the darkness? Suicide by a man who had reached the end of his rope? Murder and robbery by an opportunistic bridge guard? We'll never know for certain.

What we do know is this: Ed Delahanty was baseball's first true superstar. He was a five-tool player who could hit for average, hit for power, run, throw, and field at the highest level. He was larger than life both on and off the field. And his tragic end on a bridge over the Niagara River on July 2, 1903, remains one of the saddest and most mysterious stories in baseball history.

The game lost one of its brightest stars that night.

Baseball would go on to produce many great hitters. But there would never be another Ed Delahanty.