When Pitchers Rise to the October Moment

Trey Yesavage (RHP, TOR) started this season in Single-A ball. Seven months later, he's a World Series hero for the Toronto Blue Jays.

The 21-year-old right-hander went 1-0 with a 2.45 ERA across two World Series starts, striking out 17 batters in 11 innings while allowing just seven hits. What makes those numbers remarkable isn't just their quality—it's the contrast with his regular season debut, where he posted a 4.20 ERA in three starts for Toronto. Something clicked when the stakes were highest. His strikeout rate jumped from 13.2 per nine innings in the regular season to 13.9 in the World Series, and suddenly he looked like a completely different pitcher.

His path to October glory reads like fiction. Yesavage began 2025 with Dunedin in Single-A, where he went 3-0 with a 2.43 ERA. The Blue Jays pushed him aggressively through their system, moving him through four different levels and even touching Triple-A Buffalo before getting the call to the majors. His total minor league line showed a 3.12 ERA across 98 innings with 160 strikeouts. Then Toronto threw him into the postseason pressure cooker, and instead of melting down, he thrived.

Most rookies wilt under that kind of scrutiny. Yesavage's 0.909 WHIP in the World Series was actually better than his regular season mark of 1.133. He walked just three batters in 11 World Series innings compared to seven walks in 15 regular season frames. The kid who was facing Single-A hitters in April was suddenly overpowering the best lineup in baseball.

The jump from Single-A to World Series starter in one season is almost unheard of. But Yesavage's story fits a pattern that stretches back through baseball history—a select group of pitchers who exceed expectations on the World Series stage, delivering performances that defy explanation.

The Recent Surprise Stars

John Lackey (RHP, ANA) showed up to the 2002 World Series with exactly seven major league starts under his belt. The Angels rookie had posted a 4.63 ERA during the regular season, nothing about those numbers suggesting dominance was lurking beneath the surface.

Then October happened, and Lackey went 2-0 with a 1.29 ERA in the Fall Classic. He struck out 13 batters in 14 innings and allowed just six hits total. His inexperience actually became an asset because he didn't know enough to be nervous. The Giants couldn't figure him out, and the gap between his regular season and World Series performance tells the whole story. His ERA dropped by more than three runs. His WHIP fell from 1.48 to 0.79. This was the kind of dominance that established aces dream about, and Barry Bonds and company just couldn't solve a pitcher they'd never seen before.

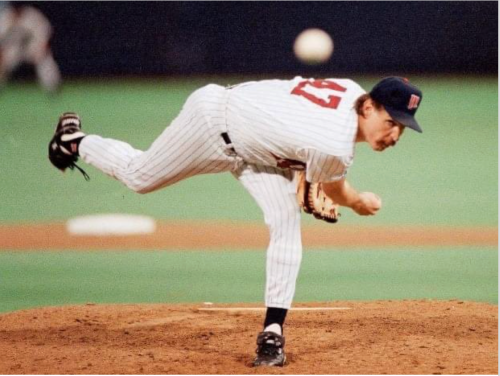

Jack Morris (RHP, MIN) carried a 3.43 ERA into the 1991 World Series—solid but unspectacular for the Twins. His postseason transformed him into a legend.

Morris went 4-0 with a 1.17 ERA across five starts, including his famous 10-inning shutout in Game 7. He pitched 60.2 innings that October, striking out 54 batters while walking just 22. The durability was remarkable, but so was the precision. His regular season WHIP of 1.25 dropped to 1.08 in the World Series. At age 36, Morris found a level nobody knew he still had.

The Braves couldn't solve him. Neither could the Pirates or Blue Jays in earlier rounds. Morris threw strikes and challenged hitters in ways he hadn't all season, and his complete game in the decisive contest remains one of baseball's iconic performances.

The 1970s Workhorses

Jack Billingham (RHP, CIN) posted a 3.04 ERA for Cincinnati during the 1972 regular season—respectable for a third or fourth starter. The Reds needed more from him in October, and Billingham delivered.

He went 2-0 with a 1.54 ERA in the World Series, striking out nine in 11.2 innings. His starts gave Cincinnati the stability they needed against Oakland. The difference between his regular season and October performance wasn't dramatic, but Billingham pitched better when it mattered most. The A's powerful lineup couldn't shake him. He mixed his pitches and changed speeds effectively, not overpowering but maddeningly consistent.

Burt Hooton's (RHP, LA) story is different. He carried a 4.24 ERA into the 1981 World Series, and the Dodgers needed length from their rotation against the Yankees. Hooton gave them something better—he went 1-0 with a 1.47 ERA across three appearances, including two starts. His knuckleball-curve combination baffled New York hitters in ways his regular season numbers never suggested it would.

Hooton struck out 13 in 12.1 innings while walking just five, impressive control considering he'd walked 60 batters in 142.1 regular season innings. His WHIP dropped from 1.43 to 0.97. Yankees hitters couldn't time his breaking stuff, and Hooton's ability to throw strikes with his curve in pressure situations gave Los Angeles a huge advantage. Tommy Lasorda trusted him in crucial spots, and Hooton responded.

1960s Boston Found an Ace

Jim Lonborg (RHP, BOS) dominated the 1967 World Series despite carrying a 3.16 ERA from the regular season. The Red Sox right-hander went 2-1 with a 2.63 ERA, striking out 22 Cardinals in 24 innings. His two victories, including a one-hitter in Game 2, kept Boston alive through sheer force of will.

Lonborg pitched on short rest in Game 7 and finally ran out of gas, but his overall performance showed how October can reveal a pitcher's true ceiling. His strikeout rate of 8.3 per nine innings in the World Series exceeded his regular season mark of 7.8. The Cardinals struggled against his fastball and curve, though they did make contact—his WHIP of 1.13 in the series actually exceeded his regular season 1.04. Still, Lonborg's ability to pitch complete games and give his team a chance to win demonstrated the kind of toughness that October demands.

The 1950s Surprises

Lew Burdette (LHP, MIL) entered the 1957 World Series with solid credentials—he'd posted a 3.72 ERA during the regular season for Milwaukee. His performance the previous year, when he won the ERA title with a 2.70 mark, suggested real capability. But what happened against the Yankees shocked everyone.

Burdette went 3-0 with a 0.67 ERA, throwing three complete games including two shutouts. He allowed just two earned runs in 27 innings, and the Yankees couldn't solve his movement. Burdette's sinker induced ground balls at a ridiculous rate. His WHIP of 0.85 represented dominance that his regular season numbers didn't hint at.

The crafty right-hander struck out 13 while walking just four. He changed speeds brilliantly and located his pitches perfectly, and New York hitters grew increasingly frustrated as Burdette kept them off balance. His Game 7 shutout clinched Milwaukee's only championship.

Don Larsen's (RHP, NYY) perfect game in 1956 stands alone in World Series history, but his regular season that year was mediocre at best. Larsen went 11-5 with a 3.26 ERA for the Yankees. He walked 64 batters in 179 innings, showing shaky control that made what came next almost impossible to believe.

Then came October 8. Larsen threw 97 pitches and retired all 27 Brooklyn Dodgers he faced. His perfect game remains the only one in World Series history, and the contrast between his season-long struggles and his moment of perfection defies logic. Larsen's WHIP for that one game was 0.00. He struck out seven and didn't go to a three-ball count on any hitter. The precision he showed that afternoon never appeared consistently during the regular season, but for nine innings, Larsen was untouchable.

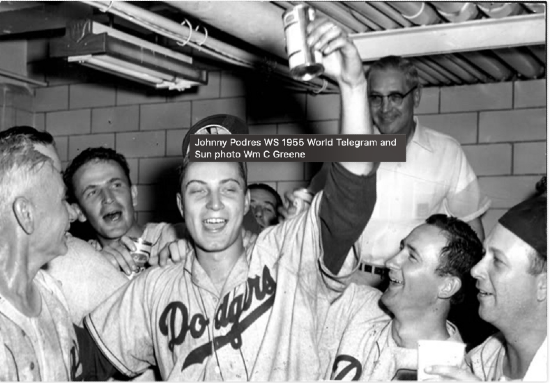

Johnny Podres (LHP, LAD) carried a 3.95 ERA into the 1955 World Series. The Dodgers left-hander had shown flashes but nothing suggesting dominance, and Brooklyn desperately needed someone to step up against the Yankees.

Podres went 2-0 with a 1.00 ERA, including a complete game shutout in Game 7. He allowed just four earned runs in 18 innings. His ability to keep the ball down and work both sides of the plate frustrated Yankees hitters, and Podres struck out eight while walking just seven, maintaining enough control to work deep into games. His WHIP of 1.00 in the series beat his regular season mark of 1.37. The 23-year-old found maturity and poise when Brooklyn needed it most, and his Game 7 shutout delivered the Dodgers' first championship.

The Old-Timers

Gene Bearden (LHP, CLE) posted a 2.43 ERA for Cleveland in 1948, his rookie season. The knuckleballer went 20-7 during the regular season, showing real promise. But his World Series performance against the Boston Braves exceeded even those numbers.

Bearden went 2-0 with a 1.50 ERA, throwing a complete game shutout in Game 3. He struck out eight in 12 innings while walking just three, and his knuckleball danced and darted in ways that left Braves hitters flailing. The movement on his pitches seemed to intensify in the bigger ballparks, and his WHIP of 0.92 in the series beat his excellent regular season mark of 1.09. Bearden's poise as a rookie facing October pressure impressed veteran teammates. He attacked hitters confidently and trusted his defense.

Harry Brecheen (LHP, STL) carried a 2.91 ERA into the 1946 World Series. The Cardinals left-hander was solid but not spectacular during the regular season—he'd gone 15-15, showing inconsistency that made you wonder if St. Louis could count on him.

October transformed him completely. Brecheen went 3-0 with a 0.45 ERA, allowing just one earned run in 20 innings across three starts. He struck out 11 Red Sox hitters while walking just three, and his screwball completely baffled Boston's lineup. The pitch moved away from right-handed hitters in ways they couldn't anticipate, and his WHIP of 0.70 represented near-perfect pitching. Brecheen threw two complete games and saved the decisive Game 7, entering in relief to record the final outs. His versatility and effectiveness would have made him the series MVP if the award had existed.

George Earnshaw (RHP, PHA) entered the 1929 World Series with a 3.29 ERA for the Philadelphia Athletics. He'd won 24 games during the regular season but also allowed his share of runs, and Connie Mack needed Earnshaw to be better in October.

He was. Earnshaw went 2-1 with a 1.58 ERA against the Cubs, striking out 13 in 17 innings. His fastball overpowered Chicago hitters who'd feasted on National League pitching all season, and Earnshaw's ability to blow hitters away gave Philadelphia a weapon few teams possessed. His WHIP of 1.12 in the series matched his regular season mark, but the strikeout rate told the real story. Earnshaw struck out 6.9 per nine innings in the World Series compared to 5.8 during the regular season. He reached back for extra velocity when the Athletics needed it most.

The pattern repeats through baseball history. Pitchers who looked ordinary during the regular season find something extra in October. Maybe it's adrenaline. Maybe it's focus. Maybe it's just the randomness of small samples working in their favor for a few crucial games.

But Trey Yesavage's journey from Single-A to World Series hero reminds us that baseball's biggest stage can reveal talents nobody knew existed. The kid was in college last year. This season started the year facing teenagers in Florida, finished it by dominating a championship lineup. That's the magic of October baseball, you never know who's going to rise to the moment.